Today's posts will cover Lawrence Weschler's “Everything that Rises: A Book of Convergences,” a finalist for the 2006 National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism.

A COUPLE OF WEEKS AGO, I found myself in a grim little bus station café in Albany. The place was a culinary wormhole back to the 1950s — coffee in Styrofoam cups, flapjacks and scrapple, chocolate malts. Since it was the only store around, and people passing through could be on the road for some time, it also sold merchandise: audio books, maps, magazines, key chains and stuffed mascots of hard-to-place sports teams. There was a rack of postcards, as well, which is where I picked up this memento of 9/11.

memento of 9/11.

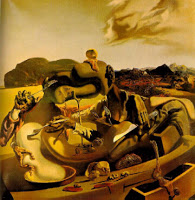

Looking at the picture – the truck so scorched it's like a skull, the dark, people-less backdrop — my mind's eye immediately leapt to Dali's paintings from the late '20s and '30s: those great bending clocks and melting faces, the twisted heaps of time's m achinery. Relativity the rupture of that generation: 9/11 the gouge through ours.

achinery. Relativity the rupture of that generation: 9/11 the gouge through ours.

I don't think I would have made this connection had I not been carrying around Lawrence Weschler's “Everything that Rises,” a contagious, profoundly playful work of cultural criticism. The book features a series of dream-like riffs on what he calls “uncanny moments of convergence, bizarre associations, eerie rhymes, whispered recollections.” In other words, one picture, reminds him of another, which reminds him of another: and then, upon scrutiny, they all (often) prove to have much deeper than surface-level associations among them.

Weschler has been collecting these “convergences” for two decades, but 9/11 is clearly the catalyst and the centerpiece. The book opens with a conversation between Weschler and photographer Joel Meyerowitz, who shot an incredible series of photographs at Ground Zero. Their conversation quickly turns from how certain images were captured, to how these photographs recall great paintings from the past. “This is Albert Bierstadt,” Weschler says, comparing one of Meyerowitz's shots to the great painter's (1868) “Among the Sierra Nevada Mountains,” to which Meyerowitz responds: “Well, I might not have been thinking specifically of Bierstadt, but I was thinking sublime, without a doubt — and for months — I was recognizing that I was in a new definition of the sublime. The awesome, horrific transformation of this place — although it wasn't nature itself — it was man acting as nature and bringing these buildings down.”

How do the images of the past determine what we see today? Is there some secret music to the universe around which human life arranges itself? And to what degree are humans making more and more of that music today? Weschler has good reason to ask these questions, because throughout this book he finds convergences between the real world and the art world, between so-called high art and low art, recent art and very, old art, between Slobodan Milosovic and Newt Gingrich. Weschler isn't the first to mine this vein – John Berger came before him, and Berger's most acutely tuned disciple, Geoff Dyer, probed it too in his terrific book of last year, “The Ongoing Moment,” which showed how photographers over the time have been taking some of the very same pictures.

In Dyer's mind, photographers are in dialogue with one another – from the dead to the living and back – on a kind of a-chronological continuum. Weschler takes this a step further – examining how the culture at large gyrates unknowingly to a trope of images, which recur across all medium – from post-cards to pin-ups to magazine covers and newspaper ads. Man's power to destroy – or at least usurp – is a constant theme as Weschler moves from artist to artist, trope to trope. A Jackson Pollock painting looks like early photographs of a far-off galaxy, first captured on film around the time Pollock reached the zenith of his powers; Rothko's last painting bears an overwhelming resemblance to photographs from the first lunar landing.

It's difficult to not draw a line between these two artists and see a defeat there of art before science – of the heavens stolen right out from beneath the noses of people like Pollock. Indeed, as Weschler points out, Rothko killed himself not long after he painted the lunar-like image. In another writer’s hands, such comparative origami would become a novelty book: a case of curiosities, sensuously wrapped. But Weschler is such a tactile writer, so filled with a kind of wonder and an eye for beauty, that “Everything that Rises” never goes that way. Rather, by reminding us of the sunken arterial ruins between art and artifact, between so-called high culture and the culture at large, this book becomes a new set of eyes for today.