Each week, the National Book Critics Circle will post a list of five books a critic believes reviewers should have in their libraries. We recently heard from Scotland on Sunday literary critic, Stuart Kelly, who is also the author of “The Book of Lost Books.” Here are the books he pointed out, adding that “first and foremost, every reviewer’s shelves ought to be sagging with contemporary and classic literature. A full knowledge of the breadth of the field of literary writing is a prerequisite to seeing through the moonshine of publicists: all those “utterly original”, “ground-breaking” and “daring” buzz words. My top five, however, would be:

Francis Jeffrey, Contributions to the Edinburgh Review (1845): the Edinburgh Review broke the mould through being independent in its opinions, unbeholden to booksellers and in introducing acerbity, pugnacity and wit to reviewing. From his damning opening of a review of the Excursion by Wordsworth (“This will never do”) to his remarkably perceptive review of Southey’s Curse of Kehama (where he berates the author for stereotyping Islam) these are endlessly interesting.

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (1927-40, 1999 edition): published posthumously, Benjamin’s Arcades Project is a rambling, unfinished, palimpsestic, infuriating masterpiece. Originally an investigation into the Parisian arcades and the flaneurs who drifted through them, it expands into a critique of nineteenth century capitalism, its origins and its future. What Benjamin excels at is taking the tiniest turn of a text and seeing the immensities behind it.

Mikhail Bakhtin, Problems in Dostoyevsky’s Poetics (1929): much of Bakhtin’s vocabulary has become second nature to a good critic: dialogism, carnivalesque, polyglossia and so forth. But this volume excels in relating the actual aesthetic of Dostoyevsky’s work to the emergent newspaper print culture, which hold, almost in stasis, tragedy and comedy, polemic and reportage. Whereas his near contemporary Lukacs seems almost quaint, Bakhtin’s legacy is endlessly fruitful.

Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism (1957): forget the rather dated material about the science of criticism, and revel in Frye’s wonderfully esoteric appreciation of the importance of form. For a reviewer, understanding generic constraints are fundamental – you can’t complain that Agatha Christie isn’t Virginia Woolf – but of equal importance is realising the rhetorical function of form, and when form itself begins to buckle and mutate.

Jacques Derrida, Dissemination (1972): but especially the section “Plato’s Pharmacy”. Most of Derrida’s detractors suffer from an essentialist kink in their psychology, as they yearn for the “message”, “ideology” or “position” to be extracted from his work. In fact, it’s about reading itself, and in this haunting engagement with Plato, Derrida unravels and unweaves the whole echo-chamber of the text. It’s profoundly poetic, rather than doctrinaire.

And, just in case these don’t suffice, Stanley Fish’s Surprised by Sin; Roland Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse; Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation, Avital Ronell’s The Telephone Book and Christine Brooke-Rose’s wonderful Textermination.

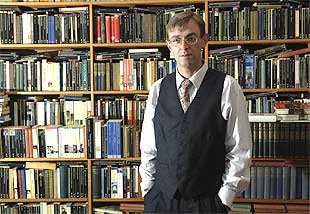

—Stuart Kelly has been investigating lost books since he was 15. He studied English at Oxford and is currently a literary critic at The Scotsman on Sunday. He has written for McSweeneys, Poetry Review and Nerve and published his first collection of poems in 2004. He lives in Edinburgh.