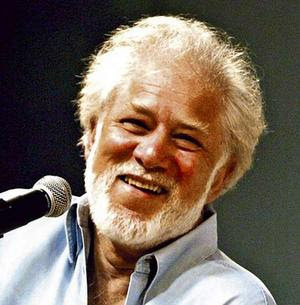

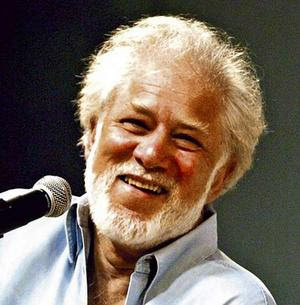

Last week, Critical Mass began publishing an essay by Molly McQuade, columnist, editor, former NBCC board member and author of the critical volumes “By Herself” and “Stealing Glimpses,” on how critics dealt with Michael Ondaatje’s latest novel, “Divisadero.”

It’s a fascinating window into the patterns and foibles of modern newspaper book reviewing. The installment publication of this piece was interrupted by the announcement of our 2007 book prize finalists. Here is part 3 of the essay. If you missed parts 1 and 2, go here and here —they’re really worth checking out.

The Bout Against a Book

The main problem with pugilistic criticism is that in the excitement of a bout against a book, the brain sighs. Incuriosity wins the fight.

For example: if, as many critics noted in passing, Ondaatje is a poet who has turned to writing fiction, then wouldn’t it be wise to wonder what abilities or inabilities a poet might bring to the writing of Divisadero? No one raised the question. No one answered it.

Giving Up

At times, I wonder why newspapers and other mass-circulation periodicals don’t just give up on book reviewing. (To say so is a heresy, coming from me, a book reviewer. Yet, candor compels me.) Why not give up, when so many reviews now seem to be assuming the function of a mere consumer advisory, with any thinking forbidden? Would it help if editors paid writers ten cents a thought, rather than five cents a word?

Yet all consumer advisories are not alike. At the Amazon.com online book site, for instance, before every book review, and just after the customer ratings of the review itself (!), there appears a pseudo-headline, in bold, which consists of a word or two or three or even four, or even a few more, forecasting just how positive or negative the review to come will be. (The ranking of bylined Amazon reviews by unnamed, anonymous Amazon customers who read them may strike us either as the most democratic of parliaments, or as the most noisome of fascist states: burdened at every level with a possibly adverse opinion of another for what we have written, we can never be quite free of public opinion in this judging of the judging of the judging.)

One such headline for a review of Divisadero by an Amazon reviewer limited itself to a single word: “Disappointing.” Another headline for a more ambivalent review summed up the novel in four words: “Facing ‘the raw truth.’ ” And an enthusiastic Amazon review of the Ondaatje novel was framed by the headline “simply beautiful, haunting and wonderful.” Look it up for yourself, why don’t you?

All of these reviews of Divisadero were posted on Amazon during the first half of last June. According to the website’s tally then, twice as many people appeared to read the rapturous Amazon review as to read the negative or ambivalent reviews of Divisadero. Still, a roughly even percentage of Amazon review readers experienced satisfaction with all three reviews—a range of five-sixths satisfied, to five-sevenths, to six-sevenths, of which the first concerned the negative review and the last the positive. Surprisingly or not, the most negative review did not substantially dissatisfy a greater proportion of Amazon customers than did the others. So, praise did not win the day.

Could this be a good sign?

Monkeyshines

Customer book reviews found at the Amazon site have been known to indulge in monkeyshines. Some professional book authors blithely encourage their friends to churn out pro-bono rave reviews on Amazon for the good of the authors, for instance. The widespread knowledge of this practice may or may not subtly distort the book reviews produced in Amazonia. Still, I doubt this happens much in the case of Ondaatje. (If it does, fellow book reviewers, please correct me.) The reviews of Divisadero—together with the ratings of those very reviews by Amazon readers—offer a curiously complete and unguarded range of opinion. Does something in Ondaatje’s writing lead silent solo readers to log on, and open their mouths? What is that certain something in his writing?

My guess is, the structurally maverick and unexpectedly poetic qualities of his prose tend to inspire conflicting opinions that feel no obligation to resolve themselves. The debate may continue, and continue. To me, this seems a rare pleasure.

Saving Time

Another pleasure of Amazon book reviews is, they save you time. You can read the review headlines, skipping the reviews themselves. The lords and masters of Amazonia seem to anticipate and enable this move. For, unlike newspaper headlines, which can sometimes stray wide of making any point, Amazon scribes and their editors are straightforward: the review headline gives you an opinion more or less identical to that of the review itself.

There is something bravely meek about those headlines, meek because without pretentions (mostly) in the writing; and brave because nothing in the words muffles the opinion. Also brave because opinions of the opinions will be tallied somehow, no matter what. And because someone soon enough will have an opinion of those opinions, and will share it, too. We are free, free, free to be smart, and we are also free not to be, aren’t we?

Aren’t we?

Free to Read

We are also free to be read, and others are free to read us, in turn. In that sense, if in no other, reviewers are much like authors, although arguably more dependent—and more incidental. In light of that, this question may not seem so very stupid: why read twenty reviews of Michael Ondaatje? Why not just read Ondaatje?

Answer: read those twenty if only because few others will. Read them on the brink of curiosity: what is there?

—Molly McQuade