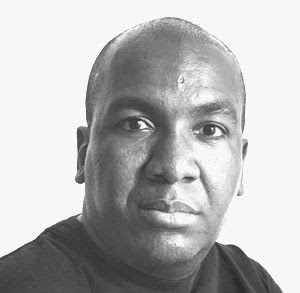

The following essay comes to us from a relatively new NBCC member, the poet and critic Reginald Shepherd, who herein describes his accidental journey into the blog world.

“Blog” is a very ugly word. It resembles the sound of someone retching. And indeed, most blogs do seem to consist of the unorganized passing contents of their authors’ minds, heaved willy-nilly onto the screen.

I am a relative newcomer to the world of blogs. Until a couple of years ago, I barely knew what a blog was, and certainly had never seen one. Mostly I used the Interweb (as Irish poet Paul Perry calls it) for email and buying things or looking for things to buy—the same things I mostly use it for now. I first stumbled upon a blog by happenstance—I was doing a web search for a poet friend of mine with whom I’d lost contact, and I came across a mention of him on the poet Joshua Corey’s blog. I was intrigued by the very interesting things Corey had to say and began a correspondence with him, some of which he posted on his blog. That blog led me to others, some of which were interesting, some of which were infuriating, most of which were just empty blather. I discovered there was an extensive world of poetry bloggers, reading and writing to one another.

Similarly, I began my own blog (to be found at http://reginaldshepherd.blogspot.com) by accident. Though I had never left a comment on a blog before, I was moved to leave one on Ron Silliman’s blog by a post of his that I found infuriating. Silliman, one of the original “Language poets,” is an elder statesman in the somewhat insular online poetry world.. Google’s Blogger software requires one to set up an account in order to leave a comment, but instead of taking me to the comment page once I had done so, the program sent me to a page to set up my own blog. The process was remarkably simple, so I said, “Why not?” A more polished and extended version of my comment became my first post.

I was quite surprised to find that, in turn, someone had left a comment on my blog within a few hours of my first post, well before I had told anyone I had a blog. I suppose that by taking on an established icon of the poetry blogosphere (another ugly word), I garnered more attention to my blog than would otherwise have been the case, though that wasn’t my intention. Perhaps I’m still a bit of a Luddite, but I still wonder: How did this person even know of my blog’s (at that point very brief) existence? It seems that there are people who do little with their time but trawl the blogosphere looking for posts relating to their interests, perhaps doing keyword searches for phrases like “fascist aesthetics.”

I am different from many poetry bloggers in that, having already published several well received books of poetry, I had an established and successful career as a writer before I started my blog. Though I definitely wanted the blog to raise my profile, and it has done so in ways I could not have anticipated and have been very gratified by, my primary intention wasn’t to announce my presence to the world, as it seems to be for most bloggers. There is a general ethos in the world of poetry blogs that its participants are outsiders. Indeed, they often feel actively excluded from some reified and monolithic idea of the poetry world and the academic world (which they tend to conflate), and nurse resentments of a sometimes frightening intensity toward those worlds and their participants. Hell, I nurse a few myself.

Though it was not a blog, the late and not-at-all-lamented site Foetry.com, ostensibly dedicated to revealing corruption in the poetry world, was a prime example of this almost Nietzschean ressentiment. Its conspiracy theories made those of Kennedy assassination fanatics seem sane and rational, and its personal attacks were never impeded or even moderated by facts. (Full disclosure: I was attacked on Foetry more than once, on one occasion over a contest I hadn’t yet finished judging.) I suspect that the level of vitriol and intellectual irresponsibility in the posts and comments on many blogs is part of their appeal, somewhat like watching The Jerry Springer Show.

The Internet is full of fools and foolishness, and has provided a forum for people to ramble and rant publicly about things of which they know nothing, or just enough to be both completely wrong and thoroughly self-righteous (a little knowledge is indeed a dangerous thing). But this is hardly a new phenomenon, nor is complaining about it. In his recent and excellently synoptic Modernism: The Lure of Heresy, intellectual historian Peter Gay includes this passage: “In 1891, Henry James lamented the overflow of literary chatter fueled by writers utterly unqualified to pronounce on such sacred subjects as contemporary fiction or poetry, music, or painting. The very multiplication of printed opinion in the Victorian age was, he wrote, summoning up his most resonant organ tones, a ‘catastrophe,’ amounting to ‘the failure of distinction, the failure of style, the failure of knowledge, the failure of thought.’” As Gay writes, “This was a little too grim-faced” (92). Plus ça change…

On the other hand, the Internet has allowed people, especially people not living in major cities, to be exposed to literary works and literary communities (virtual and often even more insular than their real-life counterparts—and yes, I do believe that there’s a difference between online life and real life) previously unavailable to those not living New York, San Francisco, Boston, Chicago, or some other major city. This is especially true for non-mainstream work and people interested in such work. I remember the effort it took to mail order a copy of The Collected Books of Jack Spicer from Black Sparrow Books when I was a teenager in Macon, Georgia in the late 1970s. There is a very extensive and geographically dispersed avant-garde poetry world online that would not exist if not for the Internet.

It’s also no coincidence that, as black people, gay people, Latino people, women, poor people, and other marginalized groups have found and taken greater opportunities to enter the public sphere and become part of the public discourse, so many complaints abound about the proliferation of the ignorant and the uninformed. All these types can be found in abundance on the Web, not to mention the monumentally self-involved, usually straight white men of various ilks who feel that their every fart is worth public note. But there is also much of interest that not only would have been difficult to find , but might not have existed at all.

As a black gay HIV positive man raised in poverty whose material circumstances are still quite precarious, I have no nostalgia for “the good old days” when things were better (for whom?), except perhaps for those bygone halcyon days when “liberal” wasn’t a dirty word. As Peter Gay’s century-old quote from Henry James demonstrates, public discourse has always been felt to be in decline. The sci-fi writer Theodore Sturgeon reportedly said some time ago that ninety percent of everything is crap. There is more sheer volume of “everything” to wade through now, but I’m not sure that the proportion of quality to crap has really changed. We only remember the best (and occasionally, the most entertainingly bad) of the past. Has anyone read the poetry of Felicia Hemans or Edwin Arnold lately?

As I said, I began my blog by accident, and for some time maintained it almost as a whim. But it has brought me many good things. I have written much more prose than I would otherwise have and, given that most of my posts, unlike other bloggers’, are extended and worked-through essays (complete with “Works Cited” lists), I have delved much more deeply into various areas of intellectual inquiry than I would otherwise have, and have discovered that I have all sorts of ideas I didn’t know I had. Indeed, in one’s year’s blogging I have produced almost a book’s worth of substantial essays—and this for someone who used to be afraid of prose. Given the highly interactive nature of the Web, I have received an amount and level of response which one almost never encounters in print media. Much of this has helped me hone and refine my thoughts.

Through my blog I have developed correspondences and virtual friendships with writers from all over the world, people I would otherwise never have encountered. I have also had some brushes with rabidly insane people, but these have been fairly brief.

Perhaps because anything online is automatically seen by geometrically more people than anything in print, it sometimes seems that my blog has done more to raise my profile than all my more-than-fifteen years of copious publishing put together, though it also seems that many who read my blog have never read my print work and never will: the Interweb is world enough for them. Within the poetry blogosphere, I have become a minor-level celebrity. I have received speaking and reading engagements, publishing opportunities, and even a part-time teaching position as a result of my blog. To an extent that I could never have anticipated, having a blog resembles Wallace Stevens’ description of writing a long poem: all kinds of favors fall from it.

Reginald Shepherd’s five books of poetry, all published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, include Fata Morgana (2007), Otherhood (2003), a finalist for the 2004 Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize, and Some Are Drowning (1994), winner of the 1993 Associated Writing Programs’ Award in Poetry. He is the editor of The Iowa Anthology of New American Poetries (University of Iowa Press, 2004) and of Lyric Postmodernisms: An Anthology of Contemporary Innovative Poetries (Counterpath Press, 2008). He is also the author of Orpheus in the Bronx: Essays on Identity, Politics, and the Freedom of Poetry (University of Michigan Press, 2008). Shepherd lives with his partner Robert Philen, a cultural anthropologist, in Pensacola, Florida, where magnolias and live oaks are evergreens