Scott Esposito edits the online magazine of book reviews and essays the Quarterly Conversation. He’s written on literature for various publications and blogs at Conversational Reading.

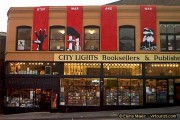

“Herta who?” aside, who says no one reads translations in America? Certainly not the audience in attendance at the NBCC Reads/Litquake translation panel hosted at City Lights on the evening of Tuesday, October 13. A crowd of 30-some braved San Francisco’s first storm of the fall to pack City Lights’ poetry room and see myself, along with NBCC Board member Oscar Villalon, uber-translator Katherine Silver, and VQR blogger Michael Lukas.

The panel began with Villalon, our able moderator, revisiting the question that originally got this conversation about translation going when last spring the NBCC canvassed its members for the translation that had most affected their reading. Looking back on my original response, I’m surprised to see that the answer I gave on the panel—that Thomas Mann’s novel Doctor Faustus is an incredible example of art that stays relevant—largely corresponds to what I wrote months ago:

Scott Esposito, the proprietor of Quarterly Conversation, turned cartwheels over Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus. “The book embodies so many currents in art and politics,” he noted. “Some of them are timeless, like the Faust legend and the question of morality in art, and some of them are historical but still remain vital (including, of course, that one big question that Jonathan Littell has just demonstrated the continuing resonance of).”

From questions of what to read the panel moved on to questions of why translation is important. Being a translator, Silver naturally had a great deal to say on that topic: she pointed out that for smaller nations like Denmark, literature in translation is essential to supporting a diverse selection of literature on bookshelves—there’s simply not enough written at home. She even discussed the extreme case of Italy, which translates so many books from English that translated literature is actually beginning to change the way Italians speak Italian.

The image of translated literature from all over the world filling a nation’s bookshelves—and perhaps even changing a nation’s substance—embodied another one of the evening’s recurrent themes: that a robust translation regime is essential to the kind of artistic cross-fertilization that has spawned intellectual innovation for centuries. To that point, Silver mentioned the case of Horacio Castellanos Moya, a Salvadorian writer she has translated and who was hugely influenced by as unlikely a source as the dour Austrian Thomas Bernhard. Though I agreed completely with Silver’s point, I was compelled to point out that in such a diverse and immigrant-heavy nation as the United States readers will often turn to English-language ethnic authors like Jhumpa Lahiri rather than seek out authors still living abroad and writing in foreign languages. Certainly the immigrant experience is an important part of American literature, I admitted, but it’s nonetheless true that these novels often take the place of literature in translation when consumers are deciding what to read. But they’re not the same thing at all.

Eventually we reached the question that it seems all conversations on translation much eventually deal with: fidelity versus transparency. Lukas noted the case of the Koran, which Muslims widely believe cannot be translated at all since, as the word of God, it will be adulterated by any translation. In response to that I noted a quote generally attributed to Borges—“Don’t translate what I wrote. Translate what I meant to write.”—as well as the case of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, who claimed that Gregory Rabassa’s English-langauge translation of One Hundred Years of Solitude is better than the original. (A great way to sell books, Silver commented.)

When the panel turned to questions from the crowd we were rewarded with several great ones. The Q & A started off with a request for a quick and easy example of something that’s untranslatable. Silver immediately rose to the challenge and defiantly said “nothing,” although I noted that tongue twisters, being highly reliant on both very particular sounds and precise meanings, are exceedingly difficult to replicate in a second language. (Readers interested in seeing that principle in action are referred to Barbara Wright’s excellent translations of Raymond Queneau, a writer who absolutely reveled in verbal game-playing and set Wright challenge upon challenge that she ably dealt with. Start with Exercises in Style.)

Another question asked whether a bad translation was better than no translation at all. Unable to come down definitively on either side, I speculated that Constance Garnett’s widely maligned translations of the great Russian novels might be an example of this, although Silver completely disagreed, even going so far as to say she wanted to start a society to rejuvenate Garnett’s image. Her point was that often the first translator of a great author is put into the very difficult position of having to translate a complex writing style without having enough leverage to persuade an editor to allow the translation to remain stylistically challenging. In Silver’s opinion, Garnett was a trailblazer working under adverse conditions, a translator who made it possible for the Pevears of the world to now perform what is perhaps more faithful renditions of the great Russian novels.

Another audience member asked if Google’s Internet library wasn’t leaving much of the world out in the cold since it was generally only making English-language books available. This excellent point left the panel speechless until Villalon stepped up with a description an interest group he’d discovered that was working on the issue of language accessibility on the Web. It seemed evident that work from such groups would be necessary to address a translation gap online.

Yet another question dealt with what exactly was meant by world literature. Michael pointed to the immense assumptions being made in any answer to such a question when he described the two “world lit” classes he’d had in college: one was composed of Greek authors while the other dealt with foundational texts from Eastern traditions. Michael seemed to sum up the matter with the mention of a third class that a friend of his was teaching: this friend taking the class as an opportunity to make students read whatever books he wanted.

The panel concluded with some thumbs-up/thumbs-down on various great works of world lit: among others, The Stranger (5 thumbs out of 6); Proust (6 thumbs, although some admission that much of it remained unread); The Windup Bird Chronicle (3 1/2 thumbs and much consternation from the audience after Katherine declared Murakami not very good).