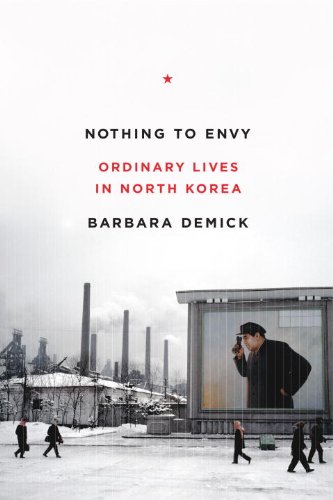

Each day leading up to the March 10 announcement of the 2010 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty-one finalists (to read other entries in the series, click here). Today, NBCC board member Art Winslow discusses nonfiction finalist Barbara Demick's Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea (Spiegel & Grau).

Each day leading up to the March 10 announcement of the 2010 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty-one finalists (to read other entries in the series, click here). Today, NBCC board member Art Winslow discusses nonfiction finalist Barbara Demick's Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea (Spiegel & Grau).

The reclusive half-peninsula that is North Korea pops in and out of Western news headlines irregularly but ominously, whether there is some new wrinkle in its nuclear status, it has bellicosely shelled a South Korean island, or there is speculation anew about a transition of power. That happened in recent days when leader Kim Jong-il’s son and heir apparent Kim Jong-un was seen publicly fitted out in a fur hat as luxurious as the one worn exclusively by his father, giving new meaning to the phrase “talking heads.”

Barbara Demick’s Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea tells us what the headlines seldom convey: that most of the 23 million inhabitants of the country find themselves interned in what is effectively a police-state gulag (where “spying on one’s countrymen is something of a national pastime”), dealing with gutted-out infrastructure, intermittent electricity, and bouts of starvation in cyclical famines. Demick, now posted in Beijing but formerly the Los Angeles Times bureau chief in Seoul, has followed the lives of several North Korean defectors to develop a chilling and extremely poignant account of everyday life within this blackout zone. That is literally true: Demick begins her book with a nighttime satellite image of part of the Far East and notes that the “large splotch curiously lacking in light” is the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

The testimony of Demick’s sources––she casts the book as “primarily an oral history,” based on seven years of conversations with North Koreans––is heart-rending, particularly when it entails children. A schoolteacher named Mi-Ran was shocked to meet students the first time and see that five- and six-year-olds “looked no bigger to her than three- and four-year-olds,” and she watched their numbers gradually diminish as they starved to death. A physician named Kim Ji-eun, another principal source, served as a pediatrician in a small district hospital and noticed that severe wasting was common: “Even four-year-olds knew they were dying and that I wasn’t doing anything to help them,” she told Demick. Her hospital was so short of supplies that bed linens were cut up for bandages and beer bottles were repurposed as IV pouches.

That same pediatrician had spent years as a dedicated supporter of the regime and the country’s single political party, the Workers’ Party; her devotion departed by degrees when she learned that even she was on a surveillance list, witnessed what she did as a physician, and further was forced to forage the countryside (even as a relatively privileged professional) for weeds to eat. Others reached disaffection without enduring such rigors: a university student found that his access to foreign books––a rarity––and television called into question the world view and cult of personality vigorously put forth by the state-controlled media.

For those who do escape the North, there is a danger of repatriation if they attempt to stay in China (crossing the Tumen River in the north of the country is a common escape route). And even life in exile for those who make it to South Korea or elsewhere can be filled with tensions of adjustment. “The sad truth is that North Korean defectors are often difficult people,” Demick observes, ones whose problems continue to trail them beyond the border.

Demick is also sensitive to the fact that “North Korea invites parody,” for the excesses of its propaganda and the seeming gullibility of its people. And yet, they are raised in a strictly hierarchical society where family background determines one’s ideological appropriateness (and thus access to anything: apartments, education, employment) in a country that has been “hermetically sealed.” Even if one were to strip away the most astonishing details of her account––North Korea’s frog population was wiped out by overhunting in the mid-1990s, although frog was not a traditional dish there, for example––Nothing to Envy would remain a compelling story of people in extremis: couples, parents, siblings, children, the imprisoned, the dead, the escapees. In her epilogue, Demick points out that the longevity of the regime “is something of a mystery to many professional North Korea watchers,” and that despite the infirmities of Kim Jong-il, “it is by no means a foregone conclusion . . . that Kim’s death would bring about the demise of the regime.” Perhaps that is why Kim Jong-un’s fur hat raised so many eyebrows.

To read an excerpt from Nothing to Envy, click here. To see Barbara Demick discuss the book at the Asia Society in New York, click here. Demick's home page, with links to numerous reviews, can be accessed here.