.jpg) Each day leading up to the March 10 announcement of the 2010 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty-one finalists (to read other entries in the series, click here). Today, NBCC board member David Biespiel discusses poetry finalist Anne Carson's Nox (New Directions).

Each day leading up to the March 10 announcement of the 2010 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty-one finalists (to read other entries in the series, click here). Today, NBCC board member David Biespiel discusses poetry finalist Anne Carson's Nox (New Directions).

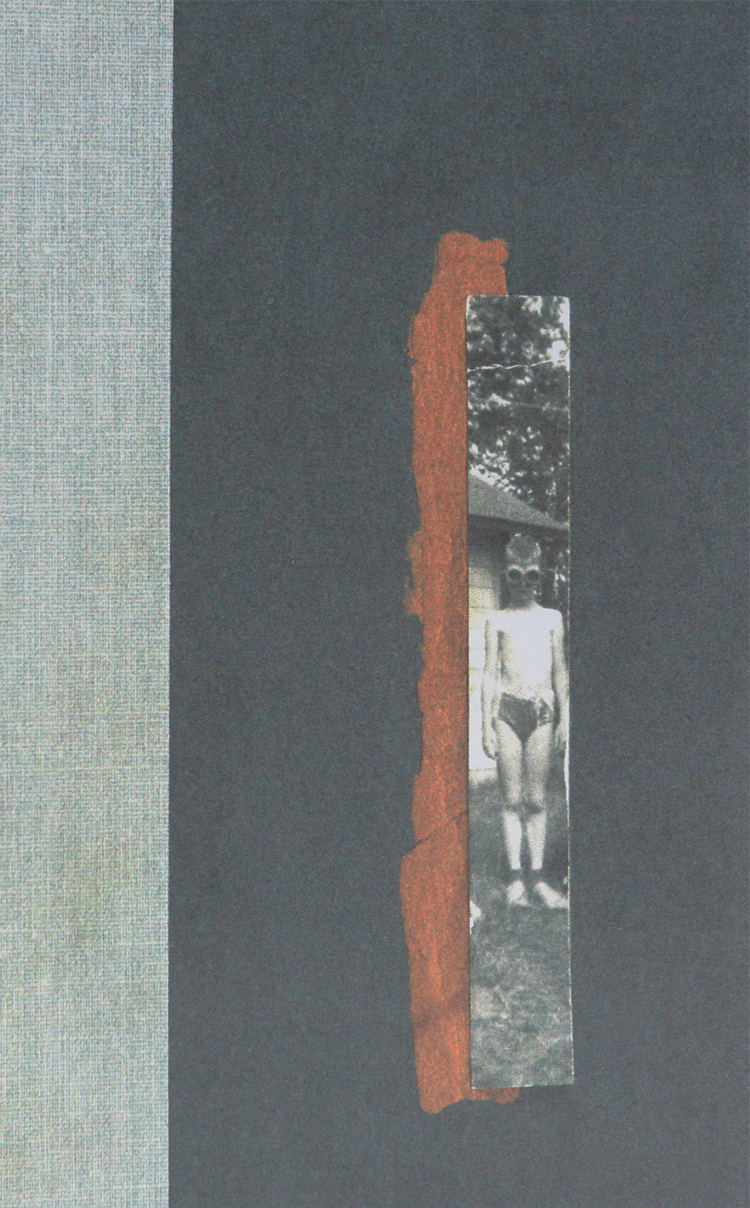

To read Nox by the Canadian poet Anne Carson is to encounter a central paradox of contemporary poetry written in English today. This special book contains photographs, ephemera, dictionary definitions, lyric shards, fragments, cutouts, clippings, handwritten jottings, and corrupted incomplete narratives, and both live and dead languages. It contains bits of uncollected memories and discarded dissolutions. It even has some lines of poems. It sits in a box and opens like an accordion––and here I am not being figurative but literal.

And yet it is also a book of poems, as I say, that consists of few if any actual poems––aside from the generative lyric at the center of the book written not by Carson but by that most sensual of Roman poets, Gaius Valerius Catullus. I mean, Nox is a sequence not of poems but of effects, a bit like a cleaning out of the closet of a dead relative, and here again I am not being figurative but literal. Nox is Anne Carson’s poetic statement about her struggle with translating, from Latin, Catullus’s famous elegy, known as Catullus 101, with its shattering final line, “atque in perpetuum, frater, ave atque vale” (something like and now and always, brother, be well, and farewell––I'm pinching that from my old college or is it high school Latin notebooks––but which Carson translates, certainly better than mine, as and into forever, brother, farewell and farewell), coupled with her own stubborn and still forming grief for the death of her late and estranged brother, Michael.

Translating and failing to translate Catullus 101 (which is Catullus’s elegy for his own brother) while also mourning and tallying the grief over the death of her brother drives the fires of the literary and the experiential in Carson’s Nox (which means, in Latin, night) into ash.

So, the book contains almost no poems, but it is, undoubtedly, poetry.

Meantime, one hears nothing but skepticism in the stingy valleys of Poetryland about Nox, I confess. “What is it?!?” is the question one hears again and again. Faced with uncertainty about what kind of book of poems Nox is, suddenly, the world of postmodern, metapoetic, cartoon-loving American poetry has caught a cold. For the last thirty years, younger American poets have tried to disentangle the poetic from the received and from the traditional. And now, with a book of poems that is more than a book of poems but not quite a book of poems, too, American poets and critics are queasy. Anne Carson’s poetry, in the spirit of disclosure, is work, in the past, that I have not held much affinity for, but she has pulled a coup against the coup of postmodernism over confessionalism. And she has made a book of poetry. And I admire it.

I’m sure the qualms in Poetryland are also symptomatic of American poetry’s general conservatism. The anodyne, imitative culture of American poetry with its little 48–60-page volumes cranked out one after another––whether the styles are experimental or mainstream––may very well just take the measure of Carson’s Nox as an anomaly and move on, back, to the same old same old. “How much money did it cost to make that thing?” one hears asked again and again about the accordion-in-a-box book from a publishing universe used to $25 entry fees and 500-book paper-only runs out of the 501c3 houses, university presses, or the small but diligent independent publishers who print their slender volumes because the good editors there believe culture is dead without the slenderest publishing object in existence, the poetry book.

Well, I hail that, too. More books! More books! But I also see Noxas potentially a ground-breaker for poetry making and producing, for poets, for audiences, and for publishers in search of something in poetry that is alive to the public and alive to the art––and credit must be given to New Directions and, I have to assume, their China-based printers for making a book of poems that’s interesting as a presentation of poetry and not just as a collection of poems. The medium is still the message, no?

So, yes, Nox sits on the desk like the color of fog in the middle of a grief-drained night, fashioned into a rectangular box that contains the souls of the dead. Yes, Nox is a box. Nox is a box with two dead brothers and a book inside. Nox is a box with two dead brothers and a dead poet and a dead language and a book inside. Nox is a keepsake, record of life, report of death, report to death, collage, sequence, series, non-poem, non-sketch, letter to the self, memo to the muses. Nox feels not corporate, not not-for-profit, not samizdat, and not POD. Nox’s scale, then, is precisely entirely human, as is its import. Nox is the very thing one expects poetry to be: emotional, wise, intelligent, and transformative. I wept when I finished reading it the first time––and I read it galleys.

Meghan O'Rourke—as smart and savvy a critic and poet as we have––characterizes Nox, in the New Yorker, as an “object.” I hate to debate her on the point because the rest of her review is reassuring, insightful, and positive, and deeply felt. But Nox is only an object if one aligns oneself with the conservative publishing production values of contemporary poetic life … well, in its conservative bona fides, too, and here I include the narrow experimentalists as well as the scrunching traditionalists, both ends of the continuum of an American poetry that has become more and more sexless, sensual-less, and cold as a television studio. But I digress. Nox is none of these things—though Carson’s past work has suffered from some of those vices.

What I mean is, New Directions may be onto something. Today’s fluid literary environment, in which the electronic and the printed more and more merge, may leave only the poets and the production of poems to redeem literary book-making. It may mean that only poetry––if it escapes the 48–60-page cell––can merge the values of the text, the artifice, the artifact, and, yes, the object into something that one dearly and deeply wants to hold. Literary art as staged performance in your hands is what I mean. A translation of grief as a translation of life as the embodiment of translating Latin into English. Like a book in a box.

That’s Nox too. Because you must hold Nox in your hands to experience it fully. I say this, but, as I admitted already, I first read Nox in galleys as a normal-like book. And that experience, prior to touching the box and the accordion fold-out paper and the embosses and the cutouts and seeing the photographs, was like entering the mind of language-less loss and language-filled awe.

So what is Nox? It is poetry. But not many poems. Nox is––actually––a facsimile of a keepsake book Anne Carson made for herself after the death of her brother, Michael, who was troubled, wayward, a runaway, and on the run. Nox is a coming to terms with Michael’s death through translating Catullus 101 (and this word, translating, can hardly cover it, translating, because the book is so much more than moving from one language identity to another). What you see is Carson attempt to translate Catullus 101 by scurrying between a pragmatic relocating of her brother’s lost life and a lyric relocating of Catullus’s lost impulses into English. And not just any Latin into English but Catullus 101! A poem that so many translators have claimed is untranslatable. It’s as if she admits that she can’t translate the Catullus 101 ever and at all––but she can perform it and she can embody its translational potential and she can enact it, all by grieving for her brother. And by doing all of that––performing, embodying, enacting, and, yes, grieving––she can collect life into a knowable poetic space, a lyric space, in which the occasion is the non-occasion. And then she can protect it in a box. As if night, nox, could be kept in the hand. Or, in an urn. Or, in a coffin.

The passages that memorialize her brother are haunting and rich and moving. But it’s the problem with translation itself that convinced me of Nox’s uniqueness and indispensable quality. To translate is to unveil the hidden. It’s to be humble before the task of bringing the cultural and literary drama of one language into another, while also being bold in the certainty that, as translator, one can actually do such a thing! Nox is the illustration of the dance of the impossibility of translation itself. Nox is the lyric failure to translate. Nox is the elegiac journey through the virtual in order to recover from an actual loss. Nox is the elegy of the elegy.

Carson is, no doubt, having to translate her estranged brother’s life, too––translating life into death, death back to life, is the central struggle for those in grief––from Michael’s original language of, say, putting his cigarette out in her eggs to her only being in contact with him for a few times throughout their life––and all of that crystallized into a scene that is stunningly sad and cryptic and full of self-awareness on his part when Anne Carson asks her troubled brother Michael if he’s happy (during a phone call about their mother’s death) and he says, “No. Oh no.” And then he adds nothing else, and she’s left trying to glean poetry from beyond the grave from a dead language.

By the time you’ve finished reading Nox and finished Carson’s re-formations, the way she breaks down each word of Catullus 101, one word at a time with denotative and connotative swoons and sonic humming, you realize that only through deconstructing the material of the Catullus poem can Carson construct the meaning of her brother’s life. And even, then, of course, in the end, that’s a failure too. The translation can’t be made. The poem can’t be written. The brother can’t be found. Best to accordion all those scatterings together, neatly, inside a box. A poetry of life.

To read an excerpt from Nox, click here.