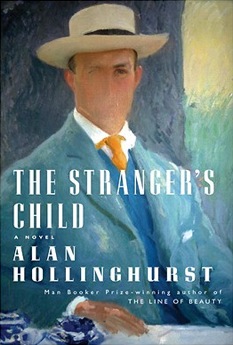

Each day leading up to the March 8 announcement of the 2011 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty finalists. Today, in #13 of our series, a fiction finalist, Alan Hollinghurst's The Stranger’s Child (Knopf), reviewed here by NBCC President Eric Banks.

Who is Cecil Valence? “Rather like the deep in Tennyson’s poem,” Alan Hollinghurst describes his poet-character creation in The Stranger’s Child, “Cecil had many voices.” The raffish young bisexual product of Edwardian-era Cambridge, “mountaineer, oarsman, and seducer” in the words of his literary executor, is a Rupert Brooke–like casualty of World War I whose verse will inspire the nation during the conflict. “A first-rate example of the second-rate poet who enters into common consciousness more deeply than many great masters,” a later exegete will put it. Valence—and his literary reputation, but as fundamentally the queer undertow he exerts on a century’s worth of friends, lovers, and later chroniclers—is the shadowy figure behind Hollinghurst’s magnificent fifth novel, a masterpiece of exacting irony and sinuous prose. The Stranger’s Child follows the peregrinations of Valence across decades of contact, all the way up to 2008, when a used-book merchant hunts for a trove of the long-dead poet's papers while fumbling with his cell phone.

At one point in The Stranger’s Child, when Valence’s executor deflects a question about the poet’s posthumous standing by remarking, “I’m a historian, not a critic,” his former lover George Sawles replies, “I’m not sure I allow a clear distinction.” The sentiment could characterize Hollinghurst himself. A novelist with a historian’s engrossment in the past and a critic’s sensitivity to taste and judgment, Hollinghurst is an aficionado of the English literary heritage, particularly its twentieth-century strain. His novels glimmer with references to his forbears; his characters eagerly offer riffs on Trollope or Firbank. In The Stranger’s Child, that bookish fascination envelops every aspect of the novel. Rupert Brooke is only one of the writers whose presence courses through the novel; you can lose count of the many others—Tennyson, Strachey, Angus Wilson, John Betjeman—who put in cameos. A more overt influence is the E. M. Forster of Howards End and of Maurice, the gay novel famously unpublishable “until my death and England’s.” Hollinghurst is a marvelous ventriloquist of the period stylings of Valence and of his brother Dudley, a caustic memoirist who marries the heroine of Valence’s idyllic summer before the War, Daphne, and inhabits the grand Valence manor, containing a supine marble statue of the fallen Cecil.

Hollinghurst has always been a novelist with a keen eye for architectural flourishes, and the fate of the Valence manor—as well as Daphne and George’s more demure Two Acres home—forms a moving counter-image to the legacy both of Cecil and of English life and literature over decades of change. What makes The Stranger’s Child truly cunning though is the extent to which literature is the landscape. The most deftly turned of Hollinghurst’s set pieces here take place in settings where the legacy of English letters is most batted about: in the cluttered offices of the TLS, where Hollinghurst himself worked for years as an editor, and at a conference on the literature of World War I at Oxford, where Cecil’s future biographer Paul is cowed by the sight of Jon Stallworthy and Paul Fussell. As the young former bank clerk turned hapless tell-all biographer attempts to track down an errant batch of letters by Cecil, he is further unnerved by the news of another writer sniffing the same trail, later identified as a textual critic who will be lauded for his “milestone work in Queer Theory.”

In richly imagining this sometimes melancholy but often quite funny path through the latter half of the last century and first years of the current one, Hollinghurst has created a twist on the historical novel glimpsed in his previous works. In the process he has managed to bridge a past and a present in a stunningly original and markedly ambitious work of fiction. That Hollinghurst is such a talented writer may even obscure his achievement. Working with a cast that is outsized in number and variety compared to his earlier novels, he inhabits all his characters with nuanced flair—no mean feat when a good half of them are venal and a good margin of others only fleetingly knowable. In that they mirror Cecil, whom everyone seems to have a purchase on yet no one every quite really knows. Ultimately, we understand as much and as little about who Cecil Valence is and was as those who cross paths with him over the course of the book. He’s as ambivalently clear and unclear as he appears in a mental picture formed by his young future biographer Paul in 1967, who thinks to himself then, “If you thought of Rupert Brooke, say, then Valence looked beady and hawkish; if you thought of Sean Connery or Elvis, he looked inbred, antique, a glinting specimen of a breed you rarely saw today.” As Valence’s story goes in and out of focus, shedding old meanings and picking up new ones, The Stranger’s Child traces a history that we think we know and realize that we never really can.