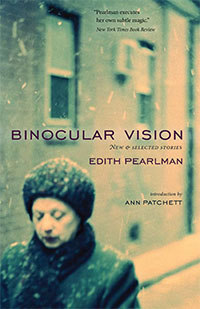

Each day leading up to the March 8 announcement of the 2011 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty finalists. Today, in #14 of our series, fiction finalist Edith Pearlman's “Binocular Vision: New and Selected Stories” (Lookout Press).

In her introduction to Edith Pearlman's “Binocular Vision,” Ann Patchett writes, “To that great list of human mysteries which includes the construction of pyramids and the persistent use of Styrofoam as a packing material let me add this one: why isn’t Edith Pearlman famous?”

It is a mystery, but perhaps “Binocular Vision” will solve it. This collection of Pearlman’s short stories, 21 drawn from across her career, 13 new, makes a convincing case that she is among the very finest writers of short fiction alive.

Set around the globe — New England, Latin America, Europe, Israel, Russia – the stories range widely but are always both surprising and exquisitely controlled. Sometimes Pearlman gives an ordinary phrase the most subtle twist and cracks open a window into another world, as in “Day of Awe,” a story in which a retiree from Boston visits an orphanage in Central America. The boys there “were respectful of his gray hairs, too. In their country a man of his age should already be dead.”

Often, Pearlman leads us into a plot that suddenly takes a turn we never saw coming and yet feels entirely right. The title story is narrated by a 10-year-old girl who whiles away winter afternoons spying on the seemingly ordinary couple next door, inventing a narrative for their marriage as she peers through their windows like someone watching a play. Like the girl, the reader thinks she knows how this domestic drama ends, until the girl’s mother upends it with a single shocking sentence. A miniature masterpiece of voice and pacing, the story is a parable of the fiction writer’s craft – and its pitfalls.

Pearlman’s stories can capture the quotidian in sparkling prose, then suddenly submerge us in the irresistible dark force of dreams or fairy tales. In ToyFolk, an American couple traveling in Central Europe is invited into a house filled with toys and a hole in the middle where a child should be, only to find that the story of why she vanished punches a hole in their relationship. “On Junius Bridge,” set in a country inn the same territory, is peopled with characters who seem to have walked right out of a folktale, even the visiting billionaire and his odd young son. Junius Bridge was once famous for an ogre that ate children, but other dangers lurk now.

Pearlman is as adept with young characters as with old ones, with both women and men. Many of her stories deal with the 20th century Jewish diaspora, from the generation that survived the Holocaust to their contemporary descendants. In Allog, the fractious but close-knit community in an apartment house in Israel is shaken up when one resident hires an Asian immigrant who challenges their notions about insiders and outsiders. In Granski, a pair of reckless teenage cousins, children of privilege whose “heroic great-grandparents” fled the Nazis, are saved from themselves by another outsider – even though she is their own grandmother.

There is much wisdom in Pearlman’s stories, always worn lightly. Jan Term takes the form of a report, complete with footnotes, written by a high school girl about her holiday volunteer project. Its description of what she learns working in an antique shop called Forget Me Not is wickedly funny — and intertwined with the poignant story, told almost between the lines, of her mother’s death and her struggle to adjust to her father’s remarriage.

The collection’s final story, the gemlike “Self-Reliance,” borrows its title from Emerson and its setting on a wooded pond from Thoreau. Its main character, a retired gastroenterologist whose cancer has recurred, is not looking for transcendence. But what she finds is what all of Pearlman’s stories lead us to, in their lapidary language, in their tenderly but frankly drawn characters, in their stories of death and love and memory: a moment of grace.

Radio interview with Pearlman.

The NYTimes review of “Binocular Vision.”

David Ulin's LATimes review.