Each day leading up to the March 8 announcement of the 2011 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty finalists. In a first, the NBCC is partnering with other websites to promote our finalists as well in the categories of Criticism and Poetry. Click here to read NBCC board members on our Poetry finalists on the website of Oprah.com. Appreciations of several of our Criticism finalists can be found at The Rumpus.

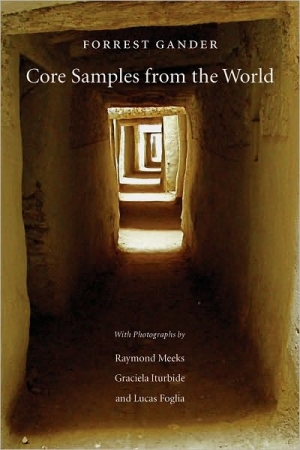

Here is #28 of our series, poetry finalist Forrest Gander's Core Samples from the World (New Directions), reviewed here by NBCC board member Craig Morgan Teicher.

Forrest Gander’s “Core Samples from the World” is an unusual book even for poetry, a genre that frequently breaks many book world rules. Gander’s poetry and prose is sequences beside black and white photos by three photographers: Raymond Meeks, Graciela Inturbide and Lucas Foglia. Certainly the words and pictures work together, but it’s not as simple as the poems describing the pictures or the pictures inspiring the poems. No, there’s something much more poetic going on, which is why this book, whose true subject is the surprisingly and constant foreignness of the world to anyone who looks at it closely, is poetry through and through.

Forrest Gander’s “Core Samples from the World” is an unusual book even for poetry, a genre that frequently breaks many book world rules. Gander’s poetry and prose is sequences beside black and white photos by three photographers: Raymond Meeks, Graciela Inturbide and Lucas Foglia. Certainly the words and pictures work together, but it’s not as simple as the poems describing the pictures or the pictures inspiring the poems. No, there’s something much more poetic going on, which is why this book, whose true subject is the surprisingly and constant foreignness of the world to anyone who looks at it closely, is poetry through and through.

It’s as though the images and poems get on each other, the way a dash of some ingredient might accidentally spill into a mixing bowl and suddenly the unsuspecting chef is making a delicacy. The photos inflect the poems, and vice versa, the way two neighboring words in a poem can subtle inflect each others’ meanings. In a poem beside a Meeks photo of two dust-covered boys carrying baskets on their heads, one up front and in focus, the other blurry in the background, Gander writes of “The sense of epoch loosened, unstrung./ Each one thinking it is the other who recedes like a horizon.” Facing an Iturbide photo of what look like rows of cactai, we read a dialogue about tending sheep in france: “They have sheep?// Sure.// How many might one shepherd have?// I don’t know, thousands.// How could they be counted.” Further down the page, in answer to the question “And what took you there?” the italicized voice offers this bracing stanza:

I was looking for bonds. I wanted to break a mirror. I wanted

to render myself accessible, available. I wanted to borrow eyes

from another language. I was looking for the words to come.

Indeed this book travels the world in the hopes of viewing others lives on their own terms: the prose sections–poetic, memoiristic prose interspersed with haiku-like lines of poetry, a Japanese essay-poem form called the haibun–that close each sequence of poems and photographs narrate Gander’s own journeys through China, Mexico, Bosnia-Hersegovnia and Chile. Much of the prose concerns cross-cultural exchanges between groups of poets from America and other countries in which they each try not to lose too much of the dark and joyful details of their native cultures in the translation, and to hold each other to the truths that words demand.

Gander has always been an innovative poet, and one deeply concerned with the events, and languages, beyond America’s borders. In this, certainly his most accessible, and possibly his most powerful, book, he brings the world’s frightening and beautiful strangeness far beyond the edge of the page.