Many of the respondents to our latest NBCC Reads question about literary journalism celebrated works of deep immersion into a topic, the product of months and sometimes years of living close to people at transformative moments in their lives. Steve Weinberg's favorite is an exemplar of the form, and an NBCC awards finalist in nonfiction in 2003. Adrian Nicole LeBlanc's Random Family, he writes, “not only is it an important story superbly told; it is also a winner due to the degree of difficulty.”

Many of the respondents to our latest NBCC Reads question about literary journalism celebrated works of deep immersion into a topic, the product of months and sometimes years of living close to people at transformative moments in their lives. Steve Weinberg's favorite is an exemplar of the form, and an NBCC awards finalist in nonfiction in 2003. Adrian Nicole LeBlanc's Random Family, he writes, “not only is it an important story superbly told; it is also a winner due to the degree of difficulty.”

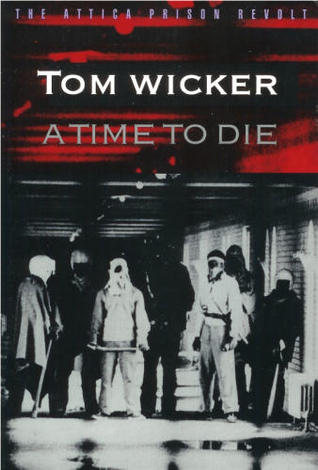

Leora Skolkin-Smith selected another eyewitness account:

Among the most powerful books of journalism and witness reporting is a book which has receded into time. Tom Wicker wrote “A Time To Die” decades ago, an eyewitness report of the Attica prison riots of 1971.Wicker was a columnist and associate editor of the New Times. Attica was a prison in upstate New York and one of many which had meager, inhumane conditions. The prisoners had demanded the presence of a group of observers to act as mediators for them. Wicker was one of those summoned. In fear of his life, Wicker repeatedly enters the besieged courtyard where a few inmates meet him and talk to him. He slowly becomes profoundly moved by the eloquence of their speeches and the sense of justice they articulate to him, as he sees, firsthand, the horror of the prison system.

Wicker's epiphanies come in the moments he attempts to persuade Governor Nelson Rockefeller to come to Attica and talk to the prisoners. He loses the gamble. Later, Wicker is tormented by conflicted feelings of humanity and real justice as he tells the prisoners, the Governor will not be arriving to negotiate, that there will be no compromises made between them and the bureaucratic prison authorities. After four days of desperate negotiations with authorities the impasse was ultimately resolved by a police attack ordered by Rockefeller. The police attack took the lives of 43 inmates and hostages. Confronting his Southern “white liberal” past, Wicker's first person witness account is made all the more poignant and pointed as he adds reminiscences of his Southern boyhood. Wicker confronts his own sleeping, masked racism, once disguised to him and supported by a too-easy American liberalism. It's one of most searing and heart-scorching witnessed accounts I have ever encountered. Wicker has a tough, precise style which is fueled by genuine social conscience. His writing and honesty made this book unforgettable to me even now in 2012.

Toni Bentley selected a brand-new example, Katherine Boo's Behind the Beautiful Forevers, and Judith Podell chose a book that, she argues, is a kind of precursor to it:

My favorite book of literary journalism? Is There No Place on Earth For Me, by Susan Sheehan, which came out in 1983. Sheehan bears witness to the life of a a schizophrenic woman in Queens, her family, and, by extension, the New York City's social service system at work. Journalism with the clear-eyed compassion of Chekhov. Before there was Katherine Boo there was Susan Sheehan.

And finally, Christina Eng selected the 1997 NBCC winner in nonfiction:

“The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down” is what first got me hooked on literary nonfiction. Anne Fadiman does a terrific job in this multi-layered work about Lia Lee, a young Hmong girl in Merced, California, with epilepsy.

She recalls awkward interactions between Lia’s family and her American doctors. She describes the friction between them, contrasting traditional Hmong beliefs with Western medical practices.

Txiv neebs (shamans), for example, could spend as many as eight hours with a sick person in her house. Doctors made their patients go to hospitals “and then might spend only twenty minutes at their bedsides… Txiv neebs could render an immediate diagnosis; doctors often demanded samples of blood… took X-rays, and waited for days for the results to come back from the laboratory – and then, after all that, sometimes they were unable to identify the cause of the problem.”

Fadiman talks also of the frustration and exasperation staff at Merced Community Medical Center occasionally felt with Lia’s case. She reveals the flipside. That Lia’s parents seldom expressed gratitude did not help.

The author uses Lia’s unique story to explore broader issues as well, looking at cultural relativism, social conflict, immigration and assimilation. She interviews leaders in Merced’s insular Hmong community, audits medical school classes at Stanford University and explores Hmong folklore and history.

With in-depth reporting, keen observation, thorough research and beautifully descriptive prose, Fadiman delivers a captivating piece of literature.