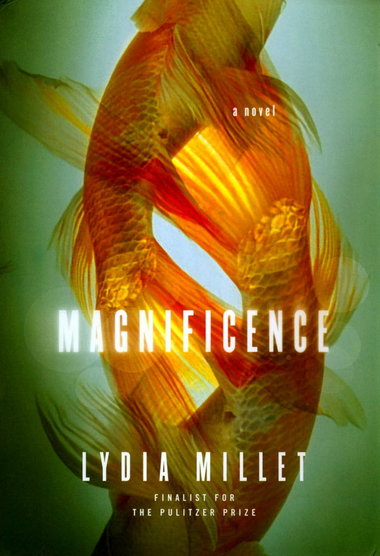

In the weeks leading up to the February 28 announcement of the 2012 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today in our series, NBCC board member David L. Ulin offers an appreciation of fiction finalist Magnificence (W.W. Norton) by Lydia Millet.

Lydia Millet’s Magnificence is a novel of ideas. The final installment in the trilogy that began with 2008’s How the Dead Dream and continued with 2011's Ghost Lights, it is an ambitious book, not so much for the sweep of its action as for its deep and nuanced investigation of all the most important issues: life, death, love, longing, extinction, the ongoing existential dilemma of what we are doing here. “In an instant,” Millet writes, “the whole of existence could go from familiar to alien; all it took was one event in your personal life. You might think you were only a mass of particles in the rest of everything, a mass exchanging itself, bit by bit, with other masses, but then you were blindsided and all you knew was the numbness of separation.”

Lydia Millet’s Magnificence is a novel of ideas. The final installment in the trilogy that began with 2008’s How the Dead Dream and continued with 2011's Ghost Lights, it is an ambitious book, not so much for the sweep of its action as for its deep and nuanced investigation of all the most important issues: life, death, love, longing, extinction, the ongoing existential dilemma of what we are doing here. “In an instant,” Millet writes, “the whole of existence could go from familiar to alien; all it took was one event in your personal life. You might think you were only a mass of particles in the rest of everything, a mass exchanging itself, bit by bit, with other masses, but then you were blindsided and all you knew was the numbness of separation.”

That’s a pretty good description of the movement of the novel, which begins with the most mundane reality: a woman named Susan driving, with her daughter Casey, to LAX to meet her husband Hal. If you’ve read How the Dead Dream or Ghost Lights, you’ll recognize these people, yet Magnificence is about more than simply closure, a revelation that asserts itself halfway through the first chapter when Susan and Casey learn that Hal has been killed and returned home as air cargo, loaded in a coffin into the belly of a plane.

Hal’s death allows Millet begins to articulate the central conundrum of the novel, which the irresolvable tension between mind and body, between what we know and what we feel. It also opens the book to unexpected humor, as Millet makes us laugh at our absurdity, our futile attempts to bestow lasting meaning, to stand up to the madness of a planet in which everything dies. Hal’s funeral is the start of it; later, Susan inherits an estate in Pasadena, only to find taxidermic specimens in every room. Were Millet out to score points — about the indulgences of the wealthy, about waste or the environment — such a moment might fall flat. Her purpose, though, is to look beyond the obvious, to see these creatures as a reflection of some desire, however misguided, to bring the dead to life.

That recalls How the Dead Dream, which involves, in part, a character’s obsession with endangered species; the fact that some of the animals here are endangered, extinct even, only ratchets up the stakes. “We are the memories of others,” Susan thinks, “we are the memory of ourselves. … The dead have sent their bodies down to be with us. … There’s still some time. We’ll keep each other company. Stay in these rooms for years and years, live on forever in a glorious museum.”

Links:

Lydia Millet's website

Boston Globe review

New York Times review