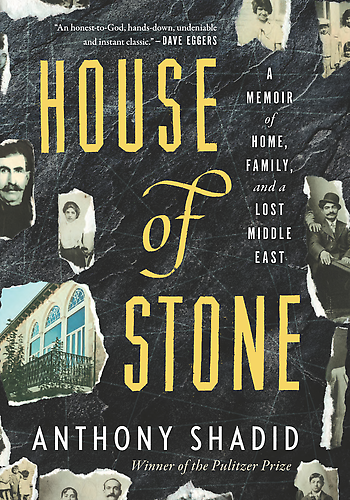

In the weeks leading up to the February 28 announcement of the 2012 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today in our series, NBCC board member Susan Shapiro offers an appreciation of autobiography finalist House of Stone: A Memoir of Home, Family, and a Lost Middle East (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) by Anthony Shadid.

“I have not always been a man who kept his promises, and I have never been the type to stay home,” admits the late Pulitzer-Prize winning Middle East correspondent Anthony Shadid, in his passionate and moving posthumous memoir House of Stone: A Memoir of Home, Family and a Lost Middle East. His third and final book chronicles the last emotional commitment he honored before he died in Syria in 2012, of an apparent asthma attack he suffered while working as the Beirut Bureau chief for The New York Times.

“I have not always been a man who kept his promises, and I have never been the type to stay home,” admits the late Pulitzer-Prize winning Middle East correspondent Anthony Shadid, in his passionate and moving posthumous memoir House of Stone: A Memoir of Home, Family and a Lost Middle East. His third and final book chronicles the last emotional commitment he honored before he died in Syria in 2012, of an apparent asthma attack he suffered while working as the Beirut Bureau chief for The New York Times.

In 2006, when the book begins, Shadid was at a crossroads. After three years covering the Iraq war for the Washington Post, he was worn out. “I was a suitcase and a laptop drifting on a conveyer belt,” he writes. “The Middle East that had fascinated, preoccupied, and saddened me for decades was gone.” Three generations after World War I drove his family out of Lebanon to Oklahoma City, the swashbuckling Lebanese Christian reporter was no longer welcome at the home he shared with his young daughter and wife in suburban Maryland. His marriage was derailed by “the lethal aspects” of his career. (Indeed, he’d been shot in the shoulder by an Israeli sniper in Ramallah, beaten while kidnapped in Libya with three other journalists for six days, and later denounced and stalked by Syrian authorities for war coverage they didn’t like. )

Instead of giving himself time to fully heal, teaching journalism in the United States and trying couples therapy, at 37 years old Shadid embarks on a year-long furlough to Beirut (of all peaceful places). Yearning for a home and a sense of belonging, he decided to reconstruct the ravaged, abandoned two-story ancestral house built in the small town of Marjayoun a century ago by his great grandfather Isber Samara. Never mind that Shadid spoke “Oklahoma-accented Arabic, sprinkled with Egyptian colloquialisms,” and he was a chain-smoking, big city intellectual with little experience in architecture or construction who, it turned out, didn’t even legally own the property. “My ambition to rebuild the house was considered foolish and rash by my new neighbors, not to mention reckless, dangerous and altogether American,” he says. The 800 people living in the town decided he was either fabulously wealthy, insane or a spy. Of course Shadid’s desperate attempt at resurrecting the residence of his forefathers becomes a poetic and political metaphor for the tragic saga of his ancestors, his former country, and the entire war-torn region.

Shadid interweaves Middle Eastern history and his own family lore into the story of his brave, poignant quixotic adventure. In the center is the house, and the hilariously funny, bickering local workers he hires for its reconstruction. His foreman, a 76-year-old theatrical diva, says things like “Money. Curse its religion, that son of a whore,” while haggling him for more. His 76-year-old stonemason recites ancient poetry while sledge hammering. His painter is color-blind. His carpenter is “so utterly lacking in punctuality that he measures time in seasons.” As the project nears completion, Shadid receives a water bill listing charges from the six years before he lived there.

He befriends the town’s most heroic man, Dr. Khairalla Mady, a 65-year-old dignified hospital administrator battling cancer. Dr. Khairalla feels betrayed when he’s accused of being an Israeli collaborator and his neighbors don’t defend him. “The closer you get to Beirut, the worse people become,” Dr. Khairalla tells him. “They’re cowards. This is their mentality. They look solely after their own interests.”

Shadid bravely depicts unlikable characters without mercy, twists old clichés into idiosyncratic parables and laces his messy, disjointed yet soulful pages with cynical wisdom. The author clearly found his subject, as if the insanity and volatility of the Middle East mirrored his anxious temperament. It’s unclear how long he was able to live in the house before he lost his life at age forty-three. He left behind his second wife, Nada Bakri, and their son, Malik, in Lebanon, and Laila, his American daughter, to whom the book is dedicated.

A wounded, middle-age asthmatic allergic to horses who chain smokes throughout a hostile, horse-filled country seems hellbent on self-destruction. Yet it’s Shadid’s irrationality and recklessness that makes this book, his last dispatch, so memorable and compelling. As he writes toward the end: “To my family, separated or reunited, Isber’s house makes a statement: Remember the past. Remember Marjayoun. Remember who are you.”

Links:

New York Times review

Washington Post review