In the weeks leading up to the February 28 announcement of the 2012 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today in our series, NBCC board member Gregg Barrios offers an appreciation of poetry finalist Useless Landscape, or A Guide for Boys (Graywolf Press) by D.A. Powell

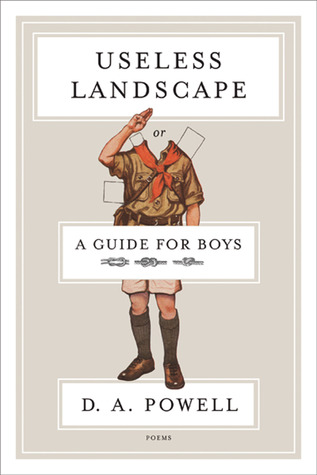

With the national controversy over whether the Boy Scouts of America should remove their ban on gay scouts and scout leaders still remains to be resolved, it must amuse poet D.A. Powell that his latest book, Useless Landscape, or A Guide for Boys might be mistaken for a Boy Scout manual or a guide for scouts or both. The book’s cover with its paper doll boy scout uniform ready to be held with folding tabs onto an unseen figure is deceiving if one notices the various knots that cover the uniform’s lower regions.

With the national controversy over whether the Boy Scouts of America should remove their ban on gay scouts and scout leaders still remains to be resolved, it must amuse poet D.A. Powell that his latest book, Useless Landscape, or A Guide for Boys might be mistaken for a Boy Scout manual or a guide for scouts or both. The book’s cover with its paper doll boy scout uniform ready to be held with folding tabs onto an unseen figure is deceiving if one notices the various knots that cover the uniform’s lower regions.

Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of the Boy Scout movement and author of Scouting for Boys: A Handbook (1908) and Aids to Scouting for NCOs and Men (1899) might well be outraged by D.A. Powell riff on his works from a gay POV that are grist for Powell’s wicked wit, puns, camp and double-entendres.

In “A Guide for Boys,” the title poem of the second section, Powell has constructed an erotic alt world based on text that might well appear in a scout manual. “The first knot doesn’t count. / You’re bound to fuck it up.” Then. “To build a fire without a match, / locate a woody-tissued branch / … / Also something to cause friction. You / may need to ask a pal for his assistance.”

In these verses, Powell constructs a palimpsest to a younger more idealized self, a guidebook that perhaps went unwritten as he – and scores of others – were growing up gay. And despite the different personae and role-playing embodied here, when the masks and the uniforms are removed, he states: “And the you here is not so much you as it is I.”

He even employs a secret language of gay camp and pig Latin. “And why not devise a language / while the bonfire dims. The camp’s / a temporary site, you say, using / Navajo Code Talker’ tongue.” It gets better. “Now add the old Caesar shifting cipher. / A dash of Latin learned at catechism /in camera, sub rosa, in flagrante delicto.”

Powell has stated that he conceived Useless as “a handbook, a manual for how to live in the rural world on the verge of changing – the world changing, but also oneself changing. I also meant it as a field guide to wildlife and wild life, both of which lurk in the bushes.”

Set in the Central Valley of California where Powell grew up, it is biographical memory and metaphor. Through Powell’s lens the area isn’t a no-man’s land but an all-men and boy’s gaylandia if you will. It is a primer and field guide to flora, fauna, faeries, fuck-ups and Funkytown.

Useless Landscape isn’t for the squeamish. Powell takes no prisoners and employs no-holds barred graphic descriptions. It may not be your cup of tea. In Tea, Powell’s first collection, he went to great length in footnotes and epigrams to clue readers the slang and argot used in homosexual circles. But that was then. Here Powell dispenses with them all together.

And yes, a lot of the knee slapping, campfire humor recalls the ribald spirit of Leslie Fiedler’s essay (“Come back to the raft, a’gin, Huck, honey”) on male bonding and homoerotic relationships in American Lit. Powell channels Huck, Whitman, Ginsberg and Jim Morrison all who lit out for the territory ahead. “The West is the best. Get here and we’ll do the rest.”

Powell chronicles this settling and trek west by gold miners, Okies, Chinese, Mexicans and Vietnamese. He views the landscape as “useless” beauty, art for arts sake, wilderness for wilderness sake, until it is cultivated, but in the process it is also ruined. Hence “Tender Mercies”:

I was a maiden in this versicolor plain.

I watched the change.

Withstood that change, the infidelities

of light, the solar interval, the shift of time,

the shift from farm to town.

I held a man that pressed me down

into the soil. I was that man. I was that town.

In the next poem, the “I” is personified: “I wasn’t the first / kid you raped. In this indifferent orchard / where many a shallow boy gets dumped.” Other poems continue this topographical lay of the land, from young men cruising and hustling in malls, underage mating in open fields, lusting in a marching band or gay bars; to older man-younger man liaisons, and living la vida loca in the boonies, looking for human contact or romance often in all the wrong but at the time very right places.

His use of poetic form runs the gamut from Pindaric odes, elegies, sonnets, benedictions, conceits, and a canticle. This is a major shift in his earlier, more experimental Tea. Still, Powell’s poetic universe is uniquely his. Nostalgic he isn’t despite have taken Wordsworth’s Ode to heart.

His manifesto since Tea has been, “this is not a book about being queer and dying. It is about being human and living.” Still in Useless Landscape he continues to acknowledges the toll AIDS has exacted, and of his own personal trials, tribulations and suffering living with HIV: “Platelet Count Descending,” “Summer of My Bone Density Test,” “Valley of the Dolls,” etc.

In Useless, Powell uses often words as mantra and incantation. His repeated use of the word “frost” – from “an early frost” to “the spiteful frost” – evokes An Early Frost (1985), the first TV network film to address the AIDS crisis. He uses this to great effect in the haiku-like “Outside Thermalito”:

Persimmons ripen with the first frost.

The bitterness inflicted on them

takes their bitterness away. nbsp;

Would that there were some other way.

Just as devastating is “Funkytown: Forgotten City of the Plain.” In that poem, with its fire and brimstone memory of Sodom and Gomorrah, the rapture occurs. Was AIDS its annunciation? The poet adds, “I’d rather withhold names. Besides, you’d read the entire list / and never know the sass and grace of them.” He then lists them lest they be forgotten. He also grapples with contrasting views of the Rapture: Are true believers taken up and others left behind? Or is there one final resurrection? “As long as there is room, why not let all the people in? / There’d be no heartache then. / We will outlast this time, my friends.”

Powell recently said, “I know there are profound mysteries throughout creation. We cannot unlock them. So I try to smash the window and crawl through it.” Shades of Robert Duncan, one of Powell’s mentors, who argued for “the very idea that there is a miraculous grace ever about us, a mystery of person.”

Another albeit less spiritual concern permeates Useless: aging and dying. “Winded, white-haired body. Splotchy skin. / My undesirable body, you’re all I have to fiddle with.” Later. “I needn’t tell you to check the mirror once in a while. I know you do. And that you’ll worry / if, like facts and blood / you, too, begin to thin.” And finally accepting his mortality: “If I can’t have my health, at least I’ll have my humor. / Good Humor. Here comes the icecream man.”

In the redemptive “Missionary Man,” the collection’s centerpiece, Powell uses epigraphs from Oscar Wilde and Isaiah, (“Together at last,” he quipped at a recent reading) to capture a moment of apotheosis. Earlier he hints: “That’s where I met him, the man who was it for now. / The Luke who was my mark. / The Matt who was my john. ” Then. “And I would ask, “are you my angel? (I got that from a book) / ((I was so unoriginal. They called me “Unoriginal Sin”)). This anticipation provides a great segue into “Missionary Man” (think the Eurhythmics’ song that opens, “Well I was born an original sinner, I was born from original sin.”)

The poem echoes a Douglas Sirk melodrama (All That Heaven Allows perhaps or Tarnished Angels – the title of an earlier poem) shot in CinemaScope. Our hero lies in a hospital bed when a young Mormon elder doing his rounds enters his room. “Let him knock with a promise of books. Good looks, / cut-away collar, skinny black tie. / The pocket protector with his name engraved.”

It is a gay fantasia moment not unlike the recent film Latter Days or reaching back to Powell’s playwriting aspirations, a riff on Tony Kushner’s Angels in America. And it is Biblical. (“I never thought of being saved, but being spent.”)

As the young missionary Jon reads from the 23rd Psalm, the poet in fevered ecstasy hears otherwise. “He prepared a place for me in empty houses / received me in the shaded summer lawns /wrapped in our own light jackets at the river bottoms.” And finally, “There is no God but that which visits us / in skin and thew and pleasing face. / He offers up this body. By this body we are saved.” This reader can only add a resounding, “Ah-Men.”

Links: