It was only in March 1997 that the NBCC decided to go global. Until then, a writer had to be an American citizen to win one of our awards. This despite the fact that we critics were often telling our readers not to miss some exciting new work by the likes of writers like Salman Rushdie and Ian McEwan, Mario Vargas Llosa and Octavio Paz, Margaret Atwood and the extraordinary Canadian short story writer Alice Munro. Not an American citizen among the lot of them!

Year after year in the mid-1990s the question of whether to open up our awards to foreign writers was hotly debated at informal get-togethers and at both general membership meetings and board meetings. Many NBCC-ers favored inclusion, but there was also considerable opposition. Making foreign writers eligible for our awards might unfairly diminish American authors’ chance of winning, argued the naysayers. Not making foreign writers eligible was demeaning to American authors, argued supporters, for the great ones deserved to be judged along with the great writers of other countries. The biggest objection of those opposing the idea of inclusion was the matter of judging a translated work. Who would we be honoring when we gave a prize to a translated author – the author or the translator? Perhaps we should just make an award for the best translation of the year. On an on discussion went. Someone floated the idea that we should exclude translated works but allow works written in English, even if the authors were not American citizens. What mattered was the language in which a work was written. This caught fire for a while.

But at the general membership meeting in March 1997, Awards Chair Alan Ryan, who had been arguing for years that the republic of letters should have no restrictions said, quite eloquently I remember thinking, “An editor once pointed out to me that our first responsibility is to the reader. And what matters in fulfilling that responsibility is the object that comes before us –- the book – no matter by whom and in what country it was written and no matter whether it’s a good translation or not. We judge the book when we review it. And we should be judging the book – just the book that is in our hands – when we make an award.” The day after that meeting, the board held a vote on the matter. Although there was still some reluctance, a motion to give our prizes to the best books of the year published in America wherever the authors hailed from prevailed, and at last our rules were changed.

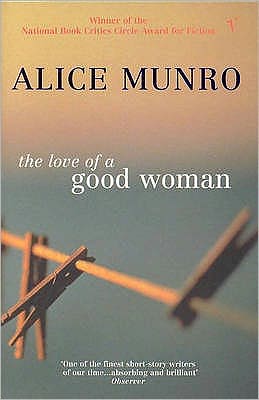

I was among those who voted for the change – and one of my main reasons for doing so was that in my opinion, in many previous years the best book of fiction to be published in America had been written by ineligible Alice Munro. A year later, in 1998, the best work of fiction published in America was by Alice Munro. The book was The Love of a Good Woman, and this time around, Munro did win our fiction award. I had the honor of presenting the award at the ceremony. And what I said of her work then – that she was surely one of the most accomplished story writers of our time— has been proven over and over again since then. The way the past haunts and shapes the present is Munro's subject. Most of her characters, like so many of us in today's world, have parted from former lovers, husbands, wives and established for themselves new, presumably more satisfying connections. But even when years have gone by, the past continues to invade, even rob, their lives. The past’s jolting disconnections, the choices made long ago, can produce “acute pain.”

In one Munro story, “The Children Stay,” the mother of two toddlers leaves her husband for the director of an amateur theatrical production and, in leaving, is forced to give up her children. They never forgive her. And her pain becomes chronic. “Chronic means,” Munro writes, “that it will be permanent but perhaps not constant. It may also mean that you won't die of it. You won't get free of it but you won't die of it. You won't feel it every minute, but you won't spend many days without it.”

Munro achieves her exquisite stories of regret, loneliness and longing by doing something few short story writers are capable of doing: by spinning the shards of past and present as if they were bits of brilliant glass in a kaleidoscope. She treats time as if it were a rubber band. And she treats character with so much nuance and psychological detail that reading a Munro short story is very much like reading a full-scale novel. So I am kvelling now that she’s won the Nobel. She once wrote about reading in her story, “Cortes Island,” that that activity can produce a “churned-up state of astonishment … a giddiness of gulped riches.” Reading a Munro story has always produced precisely that feeling in me.

More Alice Munro appreciations and remembrances from NBCCers:

NBCC award honorees Joyce Carol Oates and Lorrie Moore, NBCC member Roxana Robinson in The New Yorker.

Roxana Robinson on The Center for Fiction blog.

David Ulin talks to Margaret Atwood,Elissa Schappell, Marisa Silver, Mona Simpson, and Munro's longtime editor Ann Close.

Hector Tobar on how Alice Munro's work taught him how to 'be in the moment.'

Marcela Valdes' literary history of Alice Munro, in VQR 2006.