What is your favorite National Book Critics Circle finalist of all time? The first NBCC winners, honored in 1975 for books published in 1974, were E.L. Doctorow (Ragtime, fiction), John Ashbery (Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, poetry), R.W.B. Lewis for his biography of Edith Wharton, and Paul Fussell (The Great War and Modern Memory, criticism). In 2014 the National Book Critics Circle prepares to celebrate nearly forty years of the best work selected by the critics themselves, and also to launch the new John Leonard award for first book. So we're looking back at the winners and finalists, all archived on our website, and we've asked our members and former honorees to pick a favorite. Here's the ninth of dozens of choices in our latest in six years of NBCC Reads surveys.

A wide-eyed freshman from Berkeley on the East Coast for college, I was ready for gifts, and one early fall day, an older and onion-headed drama graduate student presented, with great flourish, a thin maroon book, titled appropriately enough THE INFINITE PASSION OF EXPECTATION by an author I'd never heard of: Gina Berriault. That drama student and I shared some kind of affinity for the West. A fur scion, he had, allegedly, assaulted Hollywood producers with great gifts — think chocolates and flowers — while Berriault was also of the west, carved of its sandstone, or at least so she seemed on the hawk-nosed semi-profile on that thin book published by North Point Press (vintage Berkeley).

Such linkage must have been enough for the drama student to loan me the book, or rather give me a gift into which I disappeared. Never have I so loved such a totem, loving it enough to have seemingly requisitioned it from him as he went on to the world of screenplays or scionhood, while I, trippingly, followed the lodestar of Fiction.

Why Berriault's stories struck me was that they were alive in the way that readers would later find life within Munro's disconsolate portals or before that in Bowles or Chekhov or Woolf, stories filled with isolates seeking connection, who could never again sing of gain, whom hope had calcified. Take that title alone, THE INFINITE PASSION OF EXPECTATION; consider the agony therein contained and how it reverberates against a title more common to that era, THE INFINITE LIGHTNESS OF BEING. Perhaps Berriault's infinite expectation was my story or perhaps the fictions of that book helped mask my own lost self, but whether or not she articulated or hid whatever self-recognition awaited me, something in the aura around Berriault — call it cathection rather than catharsis — became my hope, my own infinite passion of expectation, even as I especially loved the loneliest story in the collection, “Nights in the Gardens of Spain”, a story I have not encountered again for many years but which memory tells me relates an elder guitarist regarding a young guitarist so full of his own spliff and vigor that the elder must spend a night with burnt toast, an elegiac melody, a haunting record cover.

Like the bull's ear in A SUN ALSO RISES, that slim morocco book — for it should be called morocco rather than maroon, since North Point probably meant its color to suggest a certain class — followed me around for years, becoming my own objective correlative, hidden in this one's bedside drawer or stationed smartly on that one's shelf until it was one day finally and irretrievably lost.

In the meanwhile, I did what our age does and filled loss with information, learning more about Berriault and how she'd swanned about during the first heyday of The Paris Review, back when my own mentor Peter Matthiessen had been involved, and so I must have felt enough congruity operating to call her one day when I was back in Berkeley doing what comes easily enough in that town, which was organizing a reading of writers for the homeless. Yet it took gumption to call her and invite her to read. Calling a hero, the author of such unmet passion, meant the possibility of encountering loss: as William Gaddis says, writers are shambles following their work around. Yet since she was only across the bay, in Mill Valley, it seemed geographically if not psychologically logical to ask her to come read.

Inevitable as it was, her voice was infinitely cracked and bereft of passion. It's too late for me, she said, I don't think they want me. No, I insisted, speaking as the blind spirit of that young guitarist, please, it would be wonderful. Yet there were obtrusions, complexities, her daughter, health. She went on to speak with great candor of her bitterness that after what had been something of a meteoric start she had never been recognized by the East Coast establishment.

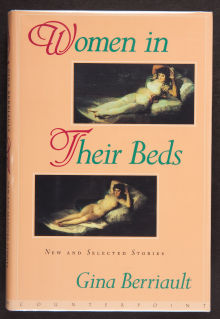

I gave up; she seemed to say, and so I followed her lead there too, going on to my own indifferent destiny, ending up in New York City one day in the mid-1990s where I was excited to learn that the National Book Critics Circle fiction award had gone to Gina Berriault for her collection, one with a title that seemed to be the conclusion to the call of that first book: WOMEN IN THEIR BEDS. Winning that award, I thought, that sad voice must have found some succor, and true enough, I heard from others at that particular ceremony that she had done what she could not to cry, practically on her knees and blessing the crowd, telling the assembled critics of the redemption she felt discovering her work had meaning for others among the metric yardsticks of the East Coast, so different from the freewheeling creativity of California, a state in which vast engines of work get created and lost. Her moment was an annunciation. And, as if she had attained her capstone, the end to all that expectation, three years later, after seventy-odd years of an elegiac consciousness, a woman in her bed, she died. Too late for me, she had said, back in the early 1990s, but at the end of her life, unlike that guitarist, she had a coda. Better late than never.