What is your favorite National Book Critics Circle finalist of all time? The first NBCC winners, honored in 1975 for books published in 1974, were E.L. Doctorow (Ragtime, fiction), John Ashbery (Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, poetry), R.W.B. Lewis for his biography of Edith Wharton, and Paul Fussell (The Great War and Modern Memory, criticism). In 2014 the National Book Critics Circle prepares to celebrate nearly forty years of the best work selected by the critics themselves, and also to launch the new John Leonard award for first book. So we're looking back at the winners and finalists, all archived on our website, and we've asked our members and former honorees to pick a favorite. Here's the thirty-first in our latest in six years of NBCC Reads surveys,

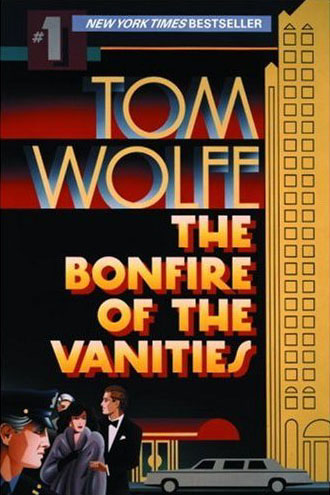

There’s something about my choice of Tom Wolfe’s 1987 blockbuster novel The Bonfire of the Vanities as my favorite NBCC winner or finalist of all time that is a little disappointing, even to myself. Anyone who was of reading age at the time will not forget how thoroughly Wolfe’s novel dominated that summer; it seemed, in its enormous hardcover edition, with the sleek Deco cover, to be everywhere. It was the kind of book that penetrated the public awareness in a way that was a little unseemly: its semi-roman a clef posturings and keen sociocultural cataloguing gave it a currency, an immediacy, that brought it an audience that normally doesn’t read literary fiction. Its success seemed thus on some level fundamentally ephemeral, and yet Wolfe’s magnum opus — for he has done nothing as good since, and likely never will — has stayed with me in a way that very, very few contemporary novels do.

I think that there are two fundamental reasons for this. The first is that Bonfire has, despite what John Updike called its “icy-hearted satire,” a moral indeterminacy that I find deeply profound. I vividly recall being startled to find, in conversation, that a close friend of mine considered the imperious WASP stockbroker Sherman McCoy to be an essentially sympathetic character, while the frustrated Jewish assistant district attorney Larry Kramer who prosecutes him was in my friend’s reading something of a villain: the opposite of the emotional affinities the novel had engendered in me. To my mind, an eight-hundred-page realist novel that is capable of producing such dissonant reactions in like-minded readers is onto something special. Wolfe's famously journalistic approach to fiction lays out the story with great fervor, but it doesn't tell you how to feel; there's room for the reader to form his own associations and judgments within the boiling cauldron of Wolfe's infernal machine. The second reason has to do with what I think of as the Huckleberry Finn hypothesis, which states that no American novel can be considered truly great unless is somehow engages the issue of race. I don’t fully subscribe to this hypothesis — it’s something I turn over in my mind late at night — but, whatever else you say about The Bonfire of the Vanities, it rotates on an axis of urban black-white relations, and it does so bluntly and forcefully. The book is big and messy and flawed and controversial and very, very funny, and for me, at least, impossible to forget or ignore.