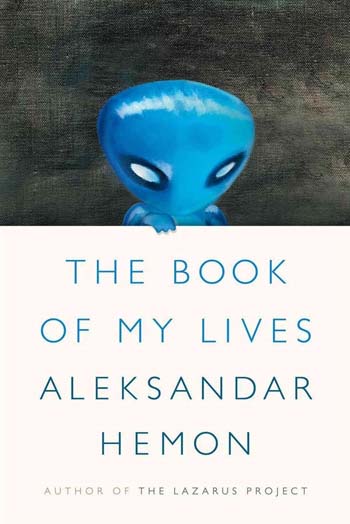

In the weeks leading up to the March 13 announcement of the 2013 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, in the fifth of our 30 Books 2013 series, NBCC board member Carmela Ciuraru offers an appreciation of autobiography finalist 'The Book of My Lives' by Aleksandar Hemon (Farrar, Straus & Giroux).

How it is that the exceedingly gifted, fiercely intelligent Bosnian native Aleksandar Hemon (who has lived in Chicago since 1992) can describe harrowing experiences of civil war, loss, and displacement, yet also manage to be so funny?

In his first book of nonfiction, “The Book of My Lives,” Hemon is a master at tonal shifts, moving seamlessly between moments of emotional devastation and dark humor. Each of these essays, with the exception of one, has been previously published, and all feature Hemon as the wry, virtuosic narrator of his own life.

Throughout, he contemplates the painful before-and-after effects of being a refugee, and the fraught meaning of home: “Immigration is an ontological crisis because you are forced to negotiate the conditions of your selfhood under perpetually changing existential circumstances,” he writes. “The displaced person strives for narrative stability—here is my story!—by way of systemic nostalgia.”

In one of the most powerful pieces in the collection, “The Book of My Life,” Hemon recalls his beloved former literature professor, Nikola Koljevic, at the University of Sarajevo. Koljevic was incredibly well read, a man who could quote Shakespeare (in English) off the top of his head, and who taught the only writing course Hemon has ever taken. Yet when Koljevic aligns himself with the fascist, genocidal Serbian Democratic Party, Hemon's awe of his teacher turns to disbelief and then repulsion. He tries in vain to identify the moment that Koljevic became a sociopath. “I unread books and poems I used to like—from Emily Dickinson to Danilo Kis, from Frost to Tolstoy—unlearning the way in which he had taught me to read them, because I should have known, I should’ve paid attention,” he writes. In 1997, Koljevic committed suicide.

Elsewhere, Hemon describes his obsession with soccer (“Not playing soccer tormented me”); the Hemon family borscht; his passion for chess-playing; the ending of his first marriage; and his devotion to his adopted hometown, featuring an “incomplete, random” list of reasons why he will never leave the city where he fell in love with his second wife, Teri. His list of Chicago's twenty virtues includes: “The green-gray color of the barely foaming lake when the winds are northwesterly and the sky is chilly.” “The summer days, long and humid, when the streets seem waxed with sweat; when the air is thick and warm as honey-sweetened tea.” And: “If Chicago was good enough for Studs Terkel to spend a lifetime in it, it is good enough for me.”

The book’s final piece, “The Aquarium,” which appeared originally in The New Yorker, is a stand-alone masterpiece. It is heartbreaking that Hemon was ever given such horrific material to work with, but in 2010, during a routine medical check, his nine-month-old daughter, Isabel, was discovered to have an extremely rare form of cancer. (“But you look good, and that’s the most important thing!” is one among many of the moronic remarks from so-called well-wishers that Hemon and his wife had to endure.) Isabel died a few months after her diagnosis. Her older sister, Ella, creates a imaginary brother called Mingus, through which she processes her unbearable grief, and for whom she invents an elaborate and ongoing plotline.

As in his works of fiction, Hemon resists a familiar narrative arc of suffering and redemption. “We learned no lessons worth learning; we acquired no experience that could benefit anybody,” he writes. “Isabel’s indelible absence is now an organ in our bodies whole sole function is a continuous secretion of sorrow.” It is hard to think of another contemporary writer who has tackled mourning with such startling candor and precision.

“The Book of My Lives” is dedicated to Isabel, “forever breathing on my chest.”

Benjamin Percy reviews “The Book of My Lives” for NPR.

Hemon interview, The New York Times.