Thanks to The School of Writing at The New School, as well as the tireless efforts of their students and faculty, we are able to provide interviews with each of the NBCC Awards Finalists for the publishing year 2013 in our 30 Books 2013 series.

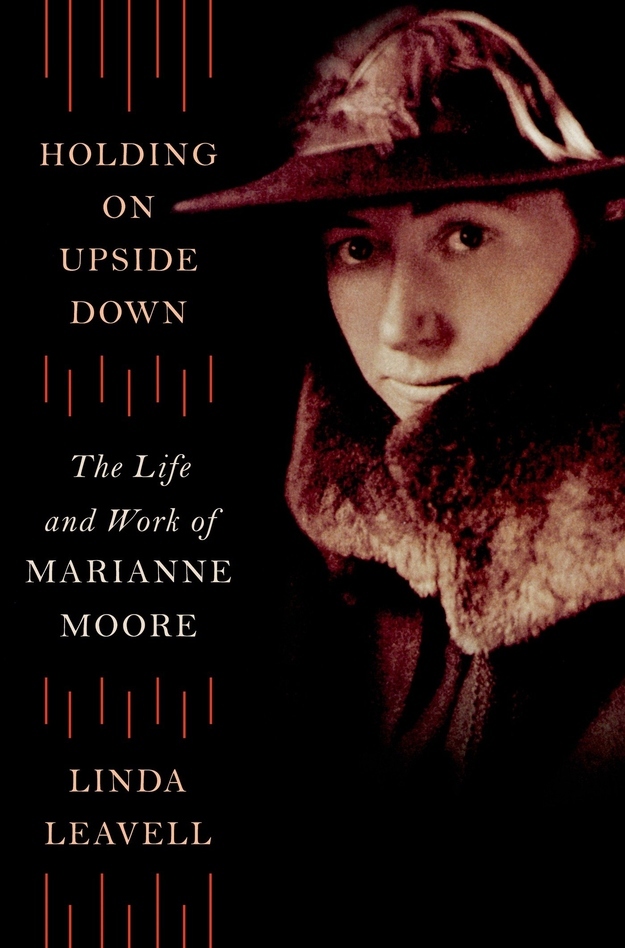

Luke Wiget, on behalf of the School of Writing at The New School and the NBCC, interviewed Linda Leavell about her book Holding On Upside Down: The Life and Work of Marianne Moore (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), which is among the final five selections, in the category of Biography, for the 2013 NBCC awards.

Luke Wiget, on behalf of the School of Writing at The New School and the NBCC, interviewed Linda Leavell about her book Holding On Upside Down: The Life and Work of Marianne Moore (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), which is among the final five selections, in the category of Biography, for the 2013 NBCC awards.

Luke Wiget: How long did you work on the book? What did that look like for you?

Linda Leavell: I wrote my dissertation on Marianne Moore thirty years ago and turned that into an academic book on Moore’s poetry and the visual arts. Fifteen years ago I began work on the biography itself when I spent a year in Philadelphia just reading in her enormous archive there. My biggest challenge was finding the story in the facts I gleaned, and that took years.

LW: The way you rendered all that research into a story is incredible, and the story is there from start to finish, never feeling overly-beholden to conveying facts. When you started this work did you have a sense of where the story would land? Was there some idea of the shape of the story?

LL: What first convinced me that there was a new story to tell was the complex relationship I discovered in the archives among Moore, her older brother, and their mother. I didn’t know then where the family dynamics would take me. I drafted about 600 pages on the first forty-two years of her life before I figured out where the story was going. Then I cut those pages by almost half to show a young poet torn between her sincere loyalty to her mother and her desire to express a sensibility at odds with the childlike role she played at home. By the time Marianne turned sixty and her mother died, she had more or less reconciled the conflict between her domestic life and her art. As a denouement to this conflict, she crafted a new persona for herself as an eccentric celebrity, an identity no one could have anticipated.

LW: You wrote in your preface that after writing those 600 draft pages you still knew little about Marianne Moore. Leon Edel, who wrote a number of biographies on Henry James—who, as you point out, was a notable influence on Moore—says: “[A] story is told brushstroke by brushstroke like a painter, and the biographer often has to say he simply doesn’t know—he cannot fill in the gaps. There’s so much that can never be known.” How did you move forward from that place? How did you work with those gaps?

LL: Edel is surely right that there is much that the biographer can never know. While I think, on the one hand, that it is irresponsible of a biographer to speculate without admitting it, I also think readers today want more than just facts from a biography. This is where imagination comes in. After writing those 600 pages, I felt that I still knew little about the poet’s innermost feelings. But that is what today’s readers of biography most want to know. I wasn’t going to say, “That’s it. Your guess is as good as mine.” Instead, I wanted to discover what I could of her inner life by connecting the dots between the events of her life and the words of her poems. However elusive the meaning of her poems, I felt them to be emotionally honest. And I tried to build trust with my readers to make a convincing case for the complex woman I portrayed.

LW: The poems are placed so thoughtfully throughout the book. You explicate them academically but always in a way that serves the story and elucidates Moore’s character. How did you choose which poems to incorporate? Was there any one poem in particular that unlocked Moore for you, where you said, oh, I understand you now?

LL: Thank you for noticing that. I had already written a book on Moore that gave lengthy analyses of individual poems, and I was writing this book for a different reader, one who wanted to know what Moore’s major achievements were but who might have little patience with long explications. I tried to give the reader a framework for reading the poems for the first time or for rereading them, but I didn’t want to detract from the aesthetic experience by over-analyzing them. I chose poems that marked turning points in her development as a poet and poems that showed her emotional response to certain events in her life. I give quite a bit of attention to Moore’s long poem, “An Octopus,” partly because I think it represents Moore at her finest and partly because I think it deserves to be better known. Reading the poems in the context of what was happening in her life at the time led to several “Aha!” moments, especially since her poems are so notoriously un-autobiographical. This happened with “The Fish” and “Marriage,” for instance. I have always liked “The Paper Nautilus” and felt gratified to discover that it confirms much of what I had concluded about Moore’s feelings regarding her art and her mother.

LW: You cite Moore as saying, “I was hand-reared. I got almost too much individual attention.” As you worked on the biography, were you able to imagine what would have come of her poems and her life, really, if she had gotten out and lived a life more separate from her mother?

LL: One does wonder. There’s a moment in 1911 when she decided to go home to take care of her broken-hearted mother rather than take a librarian job in New York. What would have become of her writing career if she’d moved to New York seven years earlier than she did? But if she had made that decision, she wouldn’t be Marianne Moore and wouldn’t have become the artist she was. As she wrote in “The Paper Nautilus,” she was “hindered to succeed.” If her reputation rested solely on the poems she wrote after her mother died, when she was no longer conflicted, she would be remembered as a minor poet at best.

LW: How much did Moore’s aesthetics play a role in yours? Did her approach inform how you crafted the book, how you chose to present Moore?

LL: Moore’s own aesthetics taught me a lot about writing her biography. Her poems are full of facts and quotations, just like biographies are, and I adopted from her the ideal she calls “relentless accuracy.” To regard a person or a thing without stereotypes, without preconceptions, without egocentricity or greed, is to give it freedom. For Moore it is nothing short of love. And yet “relentless accuracy” requires imagination as well as precision. Facts without imagination result in what she calls “the haggish, uncompanionable drawl of certitude.” From the time I started my research, I was aware that the resulting portrait would be shaped by my own imagination, and yet I felt I owed it to Moore to be as accurate as I possibly could.

LW: That’s incredibly put. It seems like those principles are not just for poets and biographers to aspire to, but for all people to keep in mind. To see the world for what it actually is seems infinitely difficult.

What’s next for you? Do you still think about Marianne Moore? Is there more to say about her?

LL: Yes, much more to say. But I’ll leave that to others. My next project is a group biography of artists and writers in the Stieglitz circle.

LW: Well, we certainly look forward to it. Thanks so much for your insight and time, and congratulations on your nomination for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

LL: Thank you, Luke.

Linda Leavell has been studying Marianne Moore’s life and work for nearly three decades. Among her previous publications is the award-winning critical study Marianne Moore and the Visual Arts: Prismatic Color. She lives with her husband in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Linda Leavell has been studying Marianne Moore’s life and work for nearly three decades. Among her previous publications is the award-winning critical study Marianne Moore and the Visual Arts: Prismatic Color. She lives with her husband in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Luke Wiget is a writer and musician born and raised in Santa Cruz, California who lives in Brooklyn, New York. His stories have appeared or are forthcoming in decomP, Hobart, SmokeLong Quarterly, Heavy Feather Review, H.O.W. Journal, among others. For questions and/or complaints find Luke on Twitter @godsteethandme

Luke Wiget is a writer and musician born and raised in Santa Cruz, California who lives in Brooklyn, New York. His stories have appeared or are forthcoming in decomP, Hobart, SmokeLong Quarterly, Heavy Feather Review, H.O.W. Journal, among others. For questions and/or complaints find Luke on Twitter @godsteethandme