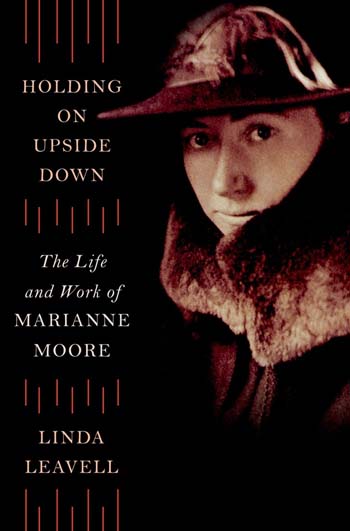

In the weeks leading up to the March 13 announcement of the 2013 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, in the eleventh of our 30 Books 2013 series, NBCC board member David Biespiel offers an appreciation of Linda Leavell's biography finalist, “Holding On Upside Down” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux).

Much has been made over the decades of Marianne Moore's, how shall I put this, idiosyncratic relationship with her mother, Mary — the daughter lived with her mother her entire adult life except for the year's she attended Bryn Mawr — and, though I mean nothing untoward about this next fact, sometimes sharing means simply sharing, shared a bed with her each night until the mother's death. That is, except when Mary, the mother, had invited her lover, another Mary (Mary Norcross who was exactly 13 years younger than Mary Moore and 13 years older than Marianne Moore) to do so. Spoiler: There are a lot of women named Mary in this book!

As I say, much has been made in the literary myth of Marianne Moore of a mother who smothered a daughter and kept her, as it were. But what of the father, John Milton Moore? Linda Leavell's authorized biography of the poet, Holding On Upside Down: The Life and Work of Marriane Moore, brings him to life in such a way as to reinsert him into the center of Moore's creative impulses.

Certainly he is a presence in Moore's poems (is he the “real toad” in her “imaginary garden,” for instance?). But he was never a presence in Moore's life. He'd gone insane when Mary was pregnant with Marianne.

What happened to him? He found too much God, is what. After his marriage to Mary, he became a religious literalist, going so far into his demonic sense of faith that he cut off his own hand. Sent to an asylum by his brother, he was kept from his wife and children. Mary forbade her two children ever to speak of him.

With that as the household's parlor backdrop, Marianne Moore turned to poetry to fill one void, independence (from a hysterical mother), and escape (from the brutal silence imposed on her from an deranged, absent father).

A life as a writer was not new to the Moore family. Marianne's grandfather, a reverend, lived in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in the middle of 19th century. When the Union and Southern armies met in battle there in the summer of 1863 and for three days bloodied each other, Moore's grandfather stayed in his living room, observed, and took notes of the entire onslaught (while his wife and his daughter — Moore's mother, that is — hid themselves for safety in the cellar). The grandfather wrote about the three-day melee and then travelled the country giving lectures about the event that proved to be a turning point in both the Civil War and American history.

His granddaughter became one of American poetry's most decorated poets, as well as fierce critic and reviewer. Her poems are shining examples of Modernism's best ambitions: they connect to the social and civic world with a prismatic filter; they stabilize emotional distress inside a fixed attention to verse (Moore's interests were with syllabics); they bring wit to agony; and they demonstrate the fractures of observation and emotion.

To unlearn the “obduracy” of her relationship with her mother and to assert “the enchantment” of the creative mind, Moore (as she does in her terrific poem, “Spencer's Ireland”), develops a knack for “disunion.” You see this characterized in the center of the poem:

It was Irish;

a match not a marriage was made

when my great great grandmother'd said

with native genius for

disunion, “Although your suitor be

perfection, one objection

is enough; he is not

Irish.” Outwitting

the fairies, befriending the furies,

whoever again

and again says, “I'll never give in,” never sees

that you're not free

until you've been made captive by

supreme belief,–credulity

you say? When large dainty fingers

tremblingly divide the wings

of the fly for mid-July

with a needle and wrap it with peacock-tail,

or tie wool and

buzzard's wing, their pride,

like the enchanter's

is in care, not madness.

This “disunion” gave her the capacity to endure a mother's fanaticism, endure a family life of absences, and thrive in the literary and social world of American poetry. Her place in American poetry is cannot be dislodged. Both Eliot and Pound champion her. Elizabeth Bishop owes nearly all of her capacity for lyric ambition to Moore's tutelage.

And now Leavell's biography underscores Moore's glowing reputation as a survivor who drew upon her canny and emotional reservoirs to create a poetry of the same.