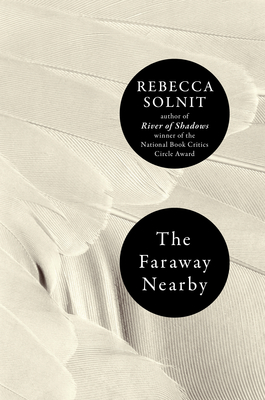

In the weeks leading up to the March 13 announcement of the 2013 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member David L. Ulin offers an appreciation of Rebecca Solnit's autobiography finalist, “The Faraway Nearby” (Viking).

Rebecca Solnit’s “The Faraway Nearby” begins with a delivery of 100 pounds of apricots to her San Francisco home. This is both narrative and allegory; the fruit, sent by her brother, comes from a tree in her mother’s yard and became “a story waiting to be told, a riddle to be solved.” This is a key theme in “The Faraway Nearby,” the idea that the stories we tell define us — which makes Solnit’s mother, in the throes of dementia, a vivid starting point. Beginning with the arrival of those apricots, “The Faraway Nearby” traces a dizzying series of narratives, both public and private, from the Arabian Nights to “Frankenstein” to Che Guevara’s “Motorcycle Diaries,” while telling us something about who we are and how we come together, or how we break apart.

The book is constructed as an elaborate palindrome, with 13 chapters that double back on one another. Her use of “Frankenstein,” for instance, is reflected later by the saga of an Inuit woman who ate the bodies of her family after being stranded on the tundra; both involve reanimation, resurrection even, and both remind us just how closely death and life are linked.

At the heart of this idea is generosity, which can be a tough sell in a culture such as ours. “[A]sking,” Solnit writes, “is difficult for a lot of people. It&rsqrsquo;s partly because we imagine that gifts put us in the giver’s debt, and debt is supposed to be a bad thing. You see it in the way people sometimes try to reciprocate immediately out of a sense that indebtedness is a burden. But there are gifts people yearn to give and debts that tie us together.”

“The Faraway Nearby” embodies just this impulse, personal without being memoiristic, setting its most intimate material within the framework of the larger world. It is a book about the psychic space of living, in which the most essential details are the most elusive, the ones that hint at how we feel. “Most fundamentally,” Solnit writes, “empathy is a mental as well as an emotional act. We must be conscious of reaching out.” Or, as she writes here in the closing pages: “Those apricots my brother brought me in three big cardboard boxes long ago, were they tears too? And this book, is it tears?”

Robin Romm's review in the New York Times

Carmela Ciuraru's review in the Boston Globe

Six questions with Solnit