In the weeks leading up to the March 13 announcement of the 2013 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Anne Trubek offers an appreciation of Franco Moretti's criticism finalist, “Distant Reading” (Verso).

Most Americans who studied literature in college did so by doing some form of what is called “close reading,” or the detailed analysis of formal elements of poems, prose and plays. Discussing rhyme schemes, allusions, symbols, word choice and of course “meaning” are a pedagogy and method so widespread we forget there are, indeed, other ways to analyze literary texts.

Enter Franco Moretti, whose collection of essays, 'Distant Reading,' makes a bold claim by its title alone. Stop debating the metaphors in T.S. Eliot, Moretti, a professor of literature at Stanford, argues. Forget learning how to read, as he puts it: let’s learn now not to read.

Huh? It is conceptually confusing to be sure: how can we study Dickens or Austen if not by taking our highlighters to key lines or making notes in the margins at some point along the way? Moretti’s answer? Make literature into data. Run books through software. Chart the sonnet.

So, for instance, in the essay “Style, Inc.: Reflections on 7,000 Titles (British Novels, 1740-1850),” Moretti counted the numbers of words in the titles of, well, 7,000 British novels published between 1740-1850. Then he plotted those numbers on an x-y axis. The result? Quantitive evidence that the length of titles dropped precipitously during this period. In the 1740, the median length of a title was 25 words; by 1850 it was 8.

So what? Is that a change that matters? Yes—just as much as a switch from a first to third person might matter—as long as you are able to put the evidence into a context that is meaningful. Which Moretti does. Titles shrunk, he argues, because “between the size of the market, and the length of titles, a strong negative correlation emerged: as the one expanded, the other contracted. Nothing much had changed, in the length of titles, for a century and a half, as long as the production of novels had remained stable around five or ten per year; then, as soon as publishing took off in earnest, titles immediately shrank.” There are other similar provocative analyses of title changes in “Style, Inc.” , how conceptual titles gave way to occupational ones and others. The data, if well analyzed, reframes how we think about 18th-century literature.

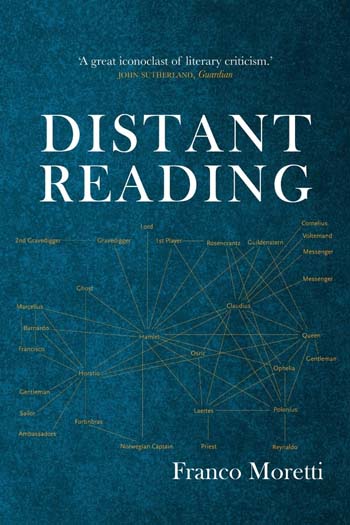

Moretti has applied his “quantitative stylistics” to the use of definite and indefinite articles in 19th-century fiction and the network structure of plots. In 'Distant Reading,' which is comprised of 10 essays written over the past 20 years, Moretti charts a scholarly journey, from the first piece, “Modern European Literature,” which works out what he calls an “evolutionary model,” to the final piece, “Network Theory, Plot Analysis,” which goes, in terms of new ways to think about what plots mean in prose, to a planet far, far away. The book itself, structured chronologically, with each essay prefaced by funny, clear introductions written after the fact, tracks Moretti’s evolution over the years as well.

Moretti’s method for gathering evidence may seem counter-intuitive, scientistic and dry, but it is in the meaning and execution that a critic is to be judged. And in those areas Moretti is anything but technical. He ruminates on, and provides compelling cultural and historical analyses for, the data he gathers. His style is as unscientific as it is writerly. He, unlike most of his academic peers, values the rhetorical, readerly purpose of criticism. His essays are fluid and pedagogical—he takes us by the hand and walks us through his ideas and, while still scholarly, his conclusions are light on declamations and heavy on a sort of wide-eyed excitement and curiousity. For example: ”for me, formal analysis is the great accomplishment of literary study, and is therefore also what any new approach—quantitative, digital, evolutionary, whatever—must prove itself against: prove that it can do formal analysis, better than we already do. Or at least: equally well, in a different key. Otherwise, what’s the point?”

As a critic, then, Moretti invites us to read closely, dwell on the page, parse his phrasing, annotate his paragraphs, and, by so doing, experiencing the attendant aesthetic pleasures of criticism. He may care less if we have read 'Bleak House' but he respects the critical curiosity of readers.

I am sure a distant reading of Moretti would yield insights. Perhaps it would be something about an overly giddy approach to data circa 2013. But by asking Big Questions and eschewing the overly technical prose of most contemporary scholarly articles, Moretti becomes, ironically, more accessible than his peers. He poses questions like, “Why are novels in prose?” Crazy, right? But a question we can all understand, even if the answers take more work to follow.

In his introduction to “The Novel: History and Theory,” Moretti writes about one scholar who is undergoing MRIs to study different types of reading: “though being strapped inside a narrow metal tube bombarded by a hammering noise is hardly the best way to read novel, she has also begun to see some extremely interesting results,” he tells us. Reading Moretti is something like the opposite of reading novels inside an MRI machine: although the evidence is not yet there about its influence and relevancy, Distant Reading, which proposes unorthodox methods through almost relatively informal, almost old-school elegance prose, is one of the best ways to read literary criticism.