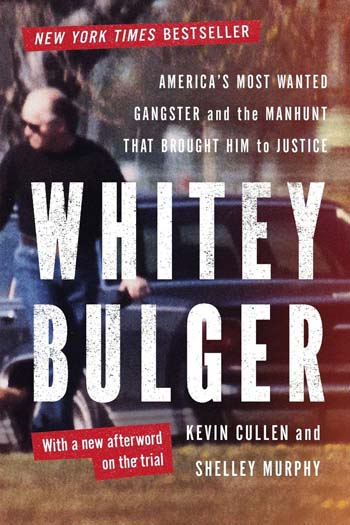

In the weeks leading up to the March 13 announcement of the 2013 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Eric Banks offers an appreciation of Kevin Cullen and Shelley Murphy's nonfiction finalist, “Whitey Bulger” (Norton).

It’s no surprise that Kevin Cullen and Shelley Murphy have combined, in Whitey Bulger: America’s Most Wanted Gangster and the Manhunt That Brought Him To Justice, to produce the most authoritative account of the rise and fall of the legendary kingpin of organized crime in Boston. After all, both journalists had covered Bulger (at considerable risk to their safety) since the 1980s, Cullen for the Globe, and Murphy originally for the Herald. Cullen was in fact the first to question the Faustian bargain that the Boston office of the FBI struck with Bulger, which gave him cover to wipe out his enemies and tipped him off to anyone who would snitch on his crimes.

Yet Cullen and Murphy have produced a book that is more than just the definitive treatment of Bulger and the Winter Hill Gang. They’ve turned out a work that sketches, in silhouette form, a rough-around-the-edges outline of Boston in its post-World War II existence, a book that speaks to one aspect of urban life that arcs up and downward over the course of its more than 450 pages. When Bulger went on trial this past summer after sixteen years on the lam for murder one—a trial that Whitey Bulger only can anticipate—it became a cliché for commentators to say that the murderer and extortionist would barely be able to recognize the yuppified South Boston of today. Cullen and Murphy’s book looks at the truth behind the stereotype and earns the fascinating lesson it offers about how the city and the criminal were intertwined.

Bulger, after all, was practically an icon of Boston. “Boston is the city of John Adams, John Kennedy, and Ted Williams, but there are few names better known or more deeply associated with the city than Bulger's,” Cullen and Murphy write. The story they tell of Bulger’s rise, along with that of his powerful politician brother Bill (president of the Massachusetts State Senate) and FBI chief John Connolly, who grew up in South Boston in the adoring shadow of tough guy Whitey and repaid his affection by long protecting him, is a story of extreme loyalty gone fatally awry in addition to an object lesson of municipal corruption. More than that, it’s the story of how a city like Boston could produce a Whitey Bulger—who cultivated his phony Robin Hood image against the backdrop of the Boston busing crisis of 1974–75, when Bulger firebombed John Kennedy’s boyhood home and even tried to blow up Plymouth Rock. Cullen and Murphy lay out the context of Boston urban politics with patience, clarity, and style; and yet they never neglect giving a human portrait of Whitey and Co.’s nineteen murder victims, from fellow low-level gangsters to a corrupt attorney they feared would sing if he got pinched, to a hapless Jai Alai executive in Tulsa who never knew who he was fronting, to the stepdaughter of one of Whitey’s henchmen.

The Bulger who emerges in Cullen and Murphy’s portrait is himself a complicated figure, “a strange and complex amalgam of the depraved and the blandly conventional.” One of the reasons Whitey Bulger is a finalist for the NBCC award in nonfiction is its success in conveying just how complicated Bulger was, and in seeing him as an exceptional product of his moment. And if that moment seems like a closed book, think again: Just recall the once-bitten, twice-shy distrust and even animosity some Bostonians harbored toward the FBI in the aftermath of the Boston Marathon terrorist attack this past spring. To get a full understanding of why that suspicion toward an agency that coddled Bulger as an ally, Whitey Bulger is an exemplary place to begin.