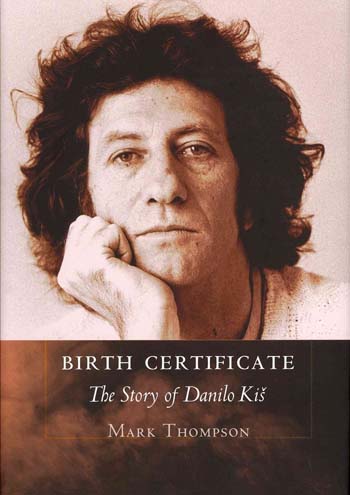

In the weeks leading up to the March 13 announcement of the 2013 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Benjamin Moser offers an appreciation of Mark Thompson's biography finalist, “Birth Certificate” (Cornell University Press).

How do you write a literary biography?

Every biographer longs to discover a form more exciting than the obvious one, the one that seems to be imposed by the chronology of a life, that succession of birthdays, schools, lovers, and books that leads inexorably toward death. When all else fails, that form will serve. But it obscures something of the magical way a reader approaches a writer he comes to love: that shiver of first contact, that book discovered by sheer chance, that personality that emerges, piece by piece, from the fragments of words that the writer has left behind. The desire a reader has—if that reader cares enough to become a literary biographer—to know more, to learn Serbo-Croatian and dig up the elderly elementary school teacher and get out the credit card to head to Tahiti for an interview that might not turn up anything—and then to take those fragments of manuscripts and letters and books and use them to piece together the lost human that produced them, the real person that is still, though long dead, hiding within all that flotsam: that is the thrill of biography, but one that the seamless linear narrative can often iron over and hide.

In “Birth Certificate: The Story of Danilo Kis,” Mark Thompson has solved this dilemma with a technique whose virtuosity lies in its simplicity. Taking a single typewritten page in which Kis once summed up in his life in a few sentences, Thompson breaks apart that simple narrative phrase by phrase, and often word by word. “My father came into the world in western Hungary and was educated at the commercial college in the birthplace of a certain Mr Virág, who would…” Kis’s account begins.

Thompson divides the sentence into chapters: “My father,” “came into the world,” “in western Hungary,” “and was educated at the commercial college in,” “the birthplace of a certain Mr Virág, who would” … and so forth, a full chapter devoted to each phrase: Kis’s father, the history of Hungary, his father’s education. The technique is a surrealist exaltation of the fragment, of the incomplete, of the forgotten and the broken, which happens to be not only a perfect way to describe a life like Kis’s, half-Jewish, half-Montenegrin, living a country, Yugoslavia, that was itself a collage of uncertainly fit-together fragments. In doing so, Thompson also answers another pressing question of literary biography:

How do you speak for a writer who seems to have been forgotten?

Writers—particularly those who write in languages rarely spoken outside their homelands—need ambassadors. Even a great writer—and there is no doubt that Danilo Kis was a great writer—needs explicators, translators, biographers, to keep his work alive, to make sure that, even long after his death, his books will still be read. And when a writer who (because dead, or Yugoslav, or only known to a small literary club) finds a biographer who is able to avoid the dutiful, dreary academic works such writers tend to attract and make a case for them to a large audience, that biographer, and that biography, deserve the support of the National Book Critics’ Circle.