This is the second of the exemplary reviews submitted by National Book Critics Circle member Katherine A. Powers, who was was awarded this year's Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing. More from her “A Reading Life” column in Barnes & Noble Review here. Thanks to the generosity of NBCC board member Gregg Barrios, the Balakian now includes a $1,000 award. Submission information for NBCC members here. The next nominations will be in November 2014.

July 31, 2013

American Pastimes: The Very Best of Red Smith

Edited by DANIEL OKRENT

Reviewed by Katherine A. Powers

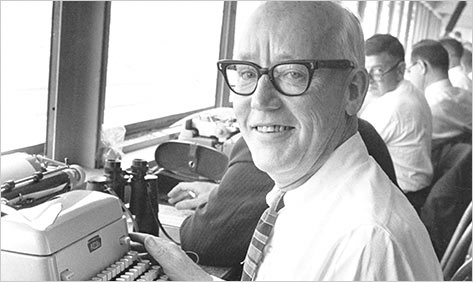

Some of America's greatest, most superbly idiosyncratic prose has come from the alcohol-fueled, tobacco-kippered, deadline-driven paws of sportswriters. Going about their business without regard for where their work might stand in the international world of letters — or, indeed, whether the uninitiated know or care what they are talking about — the nation's sportswriters write for Americans in American voices, and the great ones imbue their work with nuance and irony in a key that is completely audible only to American ears. Red Smith is unquestionably one of the great “knights of the keyboard” — to use Ted Williams's derisive term — and the Library of America now pays tribute to him in American Pastimes: The Very Best of Red Smith.

Walter Wellesley Smith was born in Green Bay, Wisconsin, in 1905, attended the University of Notre Dame, entered newspaper work, and fell into sportswriting by chance. He wrote for papers in Milwaukee, St. Louis, and Philadelphia, finally arriving, in the mid-1940s, where he had wanted to be from the start: New York City, home to the Yankees, Giants, and Dodgers; site of Madison Square Garden; and not too distant from Belmont Park and Saratoga Springs. Smith died in 1982, having, as Daniel Okrent puts it in his valuable, crisply written introduction, “traveled something like 8,000,000 words from Green Bay.”

Baseball, boxing, horse racing, and, on a less spectacular level, freshwater fishing, were Smith's particular joys; basketball and hockey were not, though he wrote about them too, a few instances of which appear in this volume. Also included are columns on Olympic contests, golf, skiing, auto and bicycle racing, and even a female weightlifter. (“For a few hours yesterday New York wore, like an orchid in her hair, a flower of femininity named Miss Dorcas Lehman, who is the strongest lady in the world.”)

There are tributes to the departed, among them Babe Ruth, surrounded at the end by “a horde of junior executives chuffing and scurrying like tugboats around a liner”; Max Baer, recalled “winding up that old Mary Ann which no other fighter of any time could throw with quite the same gaudy and destructive and altogether unforgettable flourish”; Georgie “The Iceman” Woolf, best known to us now as the jockey who rode Seabiscuit to victory over War Admiral; and doughty Seabiscuit himself. There are columns lamenting unfortunate affairs and developments: the college basketball point-shaving scandal of 1951; Cassius Clay/Muhammad Ali's triumphal eloquence (though Smith, too, came to acknowledge his greatness); the introduction of the designated hitter in the American League; and the exit of the Dodgers and Giants from New York to California (“an unrelieved calamity”).

There are panegyrics to victory and wry, funereal tributes to defeat: Smith's column on the Yankees' fifth straight World Series championship in 1953 (“Like Rooting for U.S. Steel”) begins: “The morgue doors yawned open yesterday, snapped shut, then swung open again…. The fiftieth World Series was over and this time the Dodgers really and truly were dead.”) The storied, seesaw seventh game of the 1960 World Series — in which Pittsburgh's Bill Mazeroski's ninth-inning home run off Ralph Terry defeated the Yankees — leads with a pinstriped mishap earlier in the game: “When Hal Smith hit the ball Jim Coates turned to watch its flight over left field and as it vanished beyond the ivied wall of brick the pitcher flung his glove high, as though renouncing forever the loathsome tools of his trade.”

Mazeroski's home run is, to my mind, the greatest ever struck in the history of baseball, but as New York is acknowledged to be the pivot upon which the galaxy turns, Bobby Thomson's famous — now infamous — home run of October 3, 1951, is generally given pride of place. For Okrent, Smith's piece on that game, in which Thomson's three-run shot gave the Giants the National League pennant over the ill-starred Dodgers, is “the platonic ideal of a column about a major sports event,” its first sentences “as fine a lead as any sportswriter has ever committed to paper.” Here it is: “Now it is done. Now the story ends. And there is no way to tell it. The art of fiction is dead. Reality has strangled invention. Only the utterly impossible, the inexpressibly fantastic, can ever be plausible again.”

It is a matter of taste, of course, but I could not disagree with Okrent more on this point. With its portentous, thumping tread, the specimen in question is the sort of writing that, to quote a relation of mine, “maketh the ass tired.” There is very little of it in these pages, I am happy to report, and I don't consider it typical at all of Smith's style. The aspects of Smith's writing that appeal to me are its concreteness, the deft conjuring of character, the inspired imagery, and, not least, the man's particular style of nonsense. “No mountain brook,” he writes in April 1954, “is lovelier than St. Louis' Stan Musial in his knee-sprung crouch at the plate glowering around the corner at the pitcher.” In September 1950, he finds Yankee Stadium's seats filled “half an hour before the people giving an automobile to Lefty McDermott threw out the first polysyllable.” That game, between the Yankees and Red Sox, saw Yogi Berra's “comely features” and Dom DiMaggio opening “the first inning for Boston by cowtailing a fraternal triple over the head of J. DiMaggio in center field.” While fishing in Connecticut, he observes, “Once through the narrow waist of the bridge, the stream relaxes with a soft sigh, like a lady who has removed her girdle.”

These little bubbles of whimsy and insouciance continually and merrily pop out of the simmering ebullience of his prose, seemingly effortless words that never reveal how hard they were to set down. Smith is, after all, the man who said (though, according to Okrent's research, never in print), “Writing is easy; you just open a vein and bleed.” The oft-quoted line, coming from Smith, has an engaging, self-deprecatory bounce in contrast to the martyred solemnity it assumes when attributed, as it often is, to Ernest Hemingway.

Red Smith conveys with his light irony a great truth about sports. We can care about the outcome of a given athletic contest as if all of our happiness, perhaps the fate of the world, rests on it, but we also realize, or some of us do (some of the time), how absurd this is. And that, too, is a matter for joy, the joy of relishing the beautiful folly of feeling this way about games.

Reprinted with permission of Barnes & Noble Review.