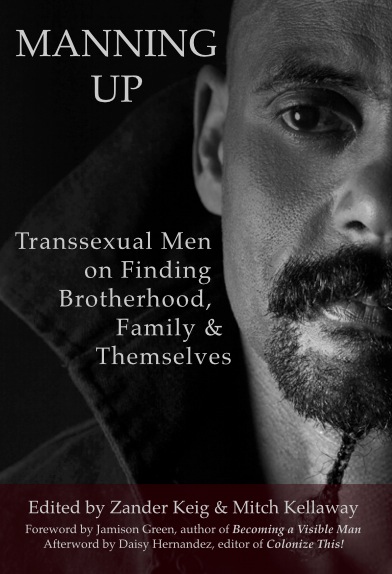

Manning Up: Transsexual Men on Finding Brotherhood, Family & Themselves, Transgress Press, 2014.

Mitch Kellaway is a Boston-based transgender writer, editor, and independent researcher. He currently covers queer literature, family rights, and transgender issues for the Advocate.com. His writing has appeared in Lambda Literary Review, Original Plumbing, The Huffington Post, Zeteo Journal, and is forthcoming in the anthologies RE*COG*NIZE: The Voices of Bisexual Men and Best Sex Writing 2015.

Zander Keig, LMSW is an award-winning speaker, outspoken advocate, dedicated mentor and educator residing in Berkeley, CA with his wife. Zander is also co-editor of the 2011 Lambda Literary Finalist Letters for My Brothers: Transitional Wisdom in Retrospect (Transgress Press, 2014).

The most recent issue of The Advocate features Laverne Cox on the cover. The article tells Cox’s powerful and inspirational story, which ends with the assertion that there are “so many trans folks coming forward and saying, ‘This is who I am, this is my story, I will not be silent anymore, I will not be hiding anymore.’ ” It struck me how the transgender narrative in the media is focused on the trans female narrative more than on the trans male one, and how books like Manning Up are doing their part to remind people that transsexual identity and life also include transgender males. But even more importantly, Manning Up opens an important forum for trans males to read about themselves and each other. Is there a resistance by the mainstream media and the population at large to listen to the trans male narrative? What are the challenges for the trans male narrative in becoming more visible and breaking down the misconceptions people have about trans men?

Mitch: Speaking about the US, I think trans male visibility has been playing catch-up to that of trans women ever since the mainstream media sensationalistically broke the story of “Ex-GI Turned Blonde Bombshell” Christine Jorgenson back in the ‘50s. That wasn’t a dynamic decided by trans people, and it troubles me whenever I see the inter-community conversation about trans men receiving less visibility veering towards a “tit-for-tat” with trans women. The popular imagination gravitated to trans women, I believe, largely because of sexist attitudes towards femininity. People simply cannot believe that a “man” would give up his social status to embody a gender ascribed lesser value within patriarchal systems. Further, because of femme-phobic taboos, there is a social sanction against men wearing women’s clothes, making women’s transitions hyper-visible. This is also why, in tandem with the more positive visibility, trans women become the target of more ire and physical abuse.

On the other hand, the mainstream can somewhat understand a “woman” wanting to take up manhood, as indicated, in part by the greater openness towards wearing men’s clothing. On the flipside, patriarchal cultures overall promote news about “men” over that of women; when the media sees trans women as “men” first-and-foremost, this contributes to interest in their stories; ironically, then, even though trans men are men, the fact that we’re often viewed first as “women”rdquo; makes our stories less newsworthy. So the fact that we’re men makes us less interesting, and the idea that we’re “women” also makes us less interesting.

But, of course, the logic of transition for trans people is not about whether it socially “makes sense” to “want” to be of another gender – which is why it’s so frustrating to come up against these frameworks. The challenge is in breaking out of that paradigm entirely – which, to me means challenging the patriarchal system. One result of this is that men (and women) are allowed more individualistic scripts for understanding their lives, and their journeys towards self-actualization are given value through experience and growth, rather than adherence or resistance to their gender’s status quo. I personally edited Manning Up in this spirit.

Zander: I believe many trans men, especially those of us who transitioned in our 30s, 40s and older, carry within us the remnants of trauma experienced as individuals assumed to be female, and especially lesbian, pre-transition. The weight of living in a sexist, oppressive, marginalizing, discriminatory and misogynistic culture is not easily put aside once testosterone hits our bloodstream. As we simultaneously learn to navigate the world of men and recover from our past traumas, we are, too often, accused of wielding “male privilege,” which many of us experience as yet one more form of bias being levied against us without our consent.

I admire the range of personal stories within the anthology. In the foreword, FTM pioneer Jamison Green writes about the contributors: “Their diverse backgrounds, ages, and racial heritage illuminate their journeys, and their histories of physical and socio-cultural obstacles enrich their appreciation of the nuances involved in taking their places among men in their spheres, as well as redefining their relationships to women. And their awareness of their transsexual status, while central for some, is never far from the surface for any of these men, as they reflect on their situations and their passages.” How did you go about collecting these personal stories? I noticed that many of the contributors are writers and bloggers or academics who would be more amenable to writing memoir than those who do not have such relationships to the written word. Why is it critical for the writer to lead the way?

Mitch: Zander started the project and I joined a year later. In many ways, our collaboration is one of two trans men a generation apart, and part of this has played out through Zander’s longevity in the trans movement. He’s the kind of guy that knows everyone, so he asked a lot of his connections to contribute essays, in addition to an online Call for Submissions. This made the collection vastly richer, because not only do we get a greater balance of middle-aged and elder trans men to the twenty- and thirty- something trans men who often dominate public dialogues, but Zander’s positive impact on other men through his activism and previous anthology (Letters for My Brothers) meant several men who had never written before felt inspired to contribute their stories. In other words, this book inspired some trans men to see themselves, even if momentarily, as writers, and as a writer myself, that makes me shiver with pride.

There are narratives in here that wouldn’t have seen light otherwise, from many men who aren’t professional writers or academics, and that feels like a critical contribution as well. While vital, scholarship often doesn’t make trans narratives more relatable or “human” in the ways that storytelling can. Our jobs as editors were then to push our 27 contributors to polish the raw material of their lives into stories – stories that can be retold as community tales, or a youth could see their future in. I personally wanted to push this book beyond the memoir genre, which has become nearly codified as the way trans folks can tell stories, and carries with it conventions that we have internalized, and which oftentimes limit the ways we come to think of and publicly portray ourselves. One way to do this was to take focus away from medical transition, and zoom on social and familial bonds, or to encourage contributions that would drill down under common experiences of male rites-of-passage.

Zander: Each trans man's transition and story is unique, yet too often a monolithic transgender tale is told, mostly from the trans female experience: trans individuals know when they are small children that they were “born in the wrong body.” I had no such revelation and know many trans men who never did either. Are we less trans because we discovered our transness in adulthood? I think not. I strive, through my books, to broaden the narrative of what it means to be transgender or transsexual. Anthologies provide the ideal platform for our unique voices to be shared and heard.

Each of the 4 sections in Manning Up is extraordinary in its own way, particularly “Part IV: New Territory” in which the contributors address male privilege and “passing,” and the knowledge that participating in the masculine world comes with the temptation of participating in sexist behavior. I appreciate how these stories are honest about their journeys: making the choice to transition is only one step–albeit an important one–toward self-realization, but transitioning is a life-long process of learning, making mistakes, encountering new challenges as others are overcome. I can envision this anthology becoming an important resource for many people. How else can I supplement my reading list that places trans male identity at the center of the narrative? What books by trans male authors have been particularly important to you that you would like to recommend?

Zander: Ten years ago, just prior to embarking on my transition journey, I read Becoming a Visible Man, written by my mentor and friend, Jamison Green. Through it's pages, I learned about, now forgotten, FTM contributions to transgender history and useful information about medically, legally and socially transitioning from female-to-male. Becoming a Visible Man was the beacon, which helped me navigate my way out from the under limited and biased notions of maleness and masculinity, gleaned during the first 39 years of my life as a female, and into a more authentic life. I recently reread the book and experienced a sense of grief when I realized the invisibility of trans men, which Jamison spoke about, was still very present today. It is my hope that books Like Manning Up and Letters for My Brothers will serve to offer a beacon for others to find their own way to their authentic self.

Mitch: You open a can of worms when you ask a bibliophile for book recommendations…I found myself, and continue to find myself anew, in books. Despite how crucial the advice and communion the Internet provides has been for trans people (I’m already working on a next book project about this!) I believe literature will always perform a special function. It goes back to that need each community has for storytellers. While I’ve read a handful of trans memoirs, I’ve gravitated towards more experimental forms, more creative nonfiction, fiction, and poetry. These are arenas where trans writing has largely been kept out by mainstream publishers, but the emergence of small presses is changing the tide.

Right now I’m really enjoying Thomas Page McBee’s Man Alive – which might be described as memoir, but is really a lyrical story about manhood. Some more of my favorites: Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics ed. by tc tolbert and Trace Peterson (Nightboat Books); The Collection: Short Fiction from the Transgender Vanguard ed. by Tom Leger and Riley McLeod (Topside Press); The Nearest Exit May Be Behind You by S. Bear Bergman (Arsenal Pulp Press). I’ve just picked up T Cooper’s Some of the Parts after several high recommendations.

I found “Part III: Family Man” to be quite moving and revelatory in terms of how each contributor spoke to the ways loved ones adapted to his transition. It really does prove that love is unconditional, which is a refreshing contrast to stories of rejection or hostility–which still happen, but if they dominate the “coming out” narrative they instill fear and anxiety more than peace and courage. I suppose that LGBTQ literature in general bears that responsibility: to communicate the individual experiences, positive and negative. Though as this anthology proves repeatedly, it’s not always one or the other–binaries are no longer the standard, we inhabit a complicated and ever-expanding gray area. After having shaped this project, in what areas of the trans male experience do you hope to see more exploration or conversation?

Zander: I believe that most people tend to occupy the “ever-expanding gray area” you speak of, yet what I have encountered along my journey from female to male, is that other people's assumptions of who you are can trump your own sense of yourself in other people's eyes. What one believes about you becomes their reality of who you are. For instance, as a trans man with an extensive lesbian and queer activist history, I remain partnered with the same woman I was with pre-transition, which now results in people concluding that I am no longer queer and possibly even “binary reinforcing,” which confounds me. This statement was uttered by a person I had never even met in person. They came to their own conclusion and acted as if it were correct. I had no say in the matter. I would like to foster more exploration and engage in dialog centered on deconstructing the notions that people have regarding what makes one “not trans enough” AND “too trans.”

Mitch: Experiences from trans men of color. Zander and I worked hard to make Manning Up a diverse project; indeed, he and I are both biracial Latino men. And overall I’m quite pleased with the reflections contributors have on the intersections of race, ethnicity, masculinity, and transition. Highlights would be “Dimension Z” by Rayees Shah, “Always Moving Forward” by Shaun LaDue, “Sculptor” by Willy Wilkinson, “Not a Caricature of Male Privilege” by Trystan Cotten and “New Territory” by Jack Sito. These essays definitely nuance the idea of transitioning into a “shared manhood” (much like feminists of color have complicated the idea of “shared womanhood”). Trans men don’t all transition to just become “men,” which was one of the projects’ cornerstone concepts. They become black men, white men, queer men, straight men, working class men, affluent men, fatherly men, single men, spiritual men, etc. etc. All of these mean different things when filtered through social and intimate, familial lenses.

One major boon of the growth in transgender literature—which, as you suggest, is an overall aim of LGBTQ literature–is that we get to tease out these complexities in lives that will be popularly portrayed as monolithic unless we provide counter-scripts.