“What's your favorite first book by an author ever?” That's the question that launches the seventh year of the NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of our members and honorees. Here's the seventh in this new series. It's not too late to send your critical essay on your own favorite to janeciab@gmail.com.

Astonishment at the quality of notable first books is often based on the dubious premise that first books are mere apprentice work, of interest primarily as the pallid chrysalis from which the neophyte butterfly will later emerge in splendid glory. In fact, however, many of the most accomplished and admired works in literary history were debut books – Lyrical Ballads, Sense and Sensibility, Frankenstein, Wuthering Heights, Buddenbrooks, Sister Carrie, The Enormous Room, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Harmonium, Flowering Judas and Other Stories, The Postman Always Rings Twice, At Swim-Two-Birds, Nausea, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, The Stranger, The Naked and the Dead, Invisible Man, The Natural, Wise Blood, Lord of the Flies, Howl, Things Fall Apart, The Leopard, Goodbye, Columbus, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Catch-22, The Bluest Eye, Bless Me, Ultima, V., Love Medicine, Everything Is Illuminated, among others. To Kill a Mockingbird is Harper Lee’s first book, though it is also her last. First books are often labors of love enriched by long gestations. Written in haste under pressure to sustain a career, second books, by contrast, can seem a letdown. Arthur Rimbaud’s decision to renounce poetry, at age 19, shortly after the publication of his first book, A Season in Hell, forestalled disappointment. Walt Whitman avoided the sophomore jinx by publishing his magnificent first book, Leaves of Grass, again and again, in five different later iterations.

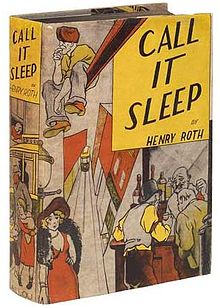

So ashamed was Nathaniel Hawthorne of his publishing debut, Fanshawe, that he attempted to retrieve and burn every copy he could find. The mediocre poetry that constitutes William Faulkner’s The Marble Faun would not be my nominee for favorite first book. Nor would I choose Edith Wharton’s debut volume on interior design, The Decoration of Houses. Instead, I call on Henry Roth’s Call It Sleep. Begun while Roth, a working-class immigrant, was still an undergraduate at City College, the novel is the finest evocation of the confrontation between European newcomers and modern urban America. The mature artistry of Roth’s first book is evident in his deft deployment of stream of consciousness; the complex portraits of young David Schearl, his frustrated, abusive father Albert, his long-suffering mother Genya, and his boisterous Aunt Bertha; and his representation of the multilingual Lower East Side in supple prose that simulates Yiddish, Polish, Hebrew, German, Italian, and various registers of English.

But what makes Call It Sleep even more striking as its author’s first book is that Roth in effect produced a second first book 60 years later. Published in 1934, in the depths of the Depression, Call It Sleep soon fell out of print and out of mind. In 1964, an ecstatic review by Irving Howe on the front page of The New York Times Book Review helped catapult Roth’s forgotten novel to the top of the bestseller lists. Meanwhile, the author himself had renounced the literary life and turned to raising and slaughtering ducks and geese in Maine. Nevertheless, in his 80s, ailing, and approaching, even embracing, death, he took up writing again, leaving behind 5,000 manuscript pages before dying, at 89, in 1995.

Roth’s second novel, A Star Shines Over Mt. Morris Park, was published in 1994, 60 years after his first. And, as the first installment of a massive tetralogy called Mercy of a Rude Stream, it represented a fresh beginning, as well as its author’s valediction to his art and his life. Mercy is a self-lacerating but also self-redeeming autobiographical fiction whose ambition to render the entirety of its author's life is unparalleled in contemporary fiction except perhaps for the six volumes of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle.

Premieres are special, hopeful occasions. But to the conscientious artist and the attentive reader, every book is the first book.