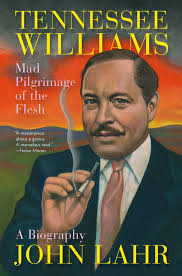

In the weeks leading up to the March 12 announcement of the 2014 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Tom Beer offers an appreciation of biography finalist John Lahr's “Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh” (W.W. Norton ).

John Lahr’s biography of Tennessee Williams begins where many show business stories climax: as the curtain goes up on opening night. The date is March 31, 1945, and Williams’ breakthrough, “The Glass Menagerie,” is about to have its Broadway premiere. The success-hungry playwright, 34, has already seen one New York–bound drama, “Battle of Angels,” flop monumentally in Boston four years before. Now, as the first scene of “Menagerie” begins, his leading lady—found on the theater steps drunk and rain-soaked just hours earlier—mistakenly lapses into some dialogue from the second act.

Despite the shaky start, Laurette Taylor will find her way back on script, delivering a seemingly miraculous performance as Amanda Wingfield, the overbearing mother who lives in the fantasy world of her past. And as the curtain came down later that evening, Lahr writes, “the audience knew that some kind of theater history had been made.” In its lyricism and “confessional style,” “The Glass Menagerie” seemed to augur, after the socio-political theater of the Depression and the war years, a new era. “With its combination of exhaustion and exhilaration, the play looked both backward and forward in time, both outward and inward. It’s romantic posture, its debate between self-sacrifice and self-interest perfectly captured the nation’s mood.” It vaulted Williams to the top rank of 20th century American dramatists.

Lahr, a longtime theater critic at The New Yorker who has written biographies of his father, actor Bert Lahr, and playwright Joe Orton, understands that a life such as Williams’s must be presented in theatrical strokes. He brings vibrant prose and a critic’s acumen to “Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh.” This is not a scholar’s dutiful, dry biography, though it is buttressed by a deep reading of Williams’s letters and notebooks, as well as interviews with surviving friends and collaborators. If the gloriously lurid subtitle (the words are Williams’ own) suggests Williams’ physical debaucheries — the youthful quest for sexual knowledge, the blur of alcohol and drugs in his later years — the book is at heart a psychological study, probing how the playwright refashioned his life experiences and psychological states into great art.

Thus Lahr is especially good on Williams’ crucial relationships, beginning with his mother, Edwina, the obvious inspiration for “Glass Menagerie’s” Amanda (“Well, Mrs. Williams, how did you like yourself” Laurette Taylor asked backstage) and his drunken salesman father, “blinkered and belligerent,” in Lahr’s words, who was recast as Big Daddy in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.” (The title itself was one of CC Williams’ typically colorful expressions.) Lahr teases out the complexities of Williams’ tempestuous relationship with his lover of 15 years, Frank Merlo, who grounded the playwright but was also bitterly jealous of his success. (Shades of Merlo can be seen in Mangiacavallo, the lusty truck driver of “The Rose Tattoo.”) For students of the theater, perhaps the most fascinating passages illuminate Williams’ intense creative collaboration with director Elia Kazan, who was, Lahr writes, “a kind of luminous, empowering father figure,” deeply involved in the shaping of “A Streetcar Named Desire” “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” “Sweet Bird of Youth,” and other productions.

Though Tennessee Williams didn’t have a hit play after “The Night of the Iguana” in 1960, he kept on writing. Lahr’s interest in the work never flags, finding insights even in the failures. The end—in a “sour, pill-strewn” New York hotel room in 1983—was tawdry, and Lahr doesn’t morbidly linger on it. Instead he turns to consider Williams’s legacy, one jeopardized by the capriciousness of his estate, which stymied productions of the plays and biographical inquiries for more than a decade. Lahr sees past it all to identify an artistic bravery in his subject, of a kind that seems rare in today’s commercial theater. “In him, until his last breath,” Lahr writes, “the forces of life and death were pitched in clamorous battle. Art was his habit, his ‘fatal need,’ and his salvation.”

Review by Wendy Smith in The Daily Beast.

Review by Gerald Bartell in The San Francisco Chronicle.

Review by Charles Matthews in The Washington Post.

Review by J.D. McClatchy in The Wall Street Journal.