In the weeks leading up to the March 12 announcement of the 2014 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Colette Bancroft offers an appreciation of nonfiction finalist Hector Tobar's “Deep Down Dark” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux).

In 2010, 33 men were trapped thousands of feet underground by a massive rock fall in a mine in Chile. The news went global, and it stayed that way for 69 days, until their astonishing rescue.

One of the countless remarkable things about their story was a pact the miners made while still trapped: “They will not reveal, individually, what they suffered as a group. That story is their most precious possession, and it belongs to all of them.”

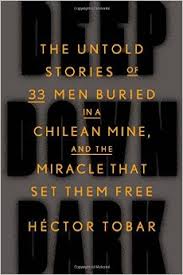

Journalist Hector Tobar tells that story, and tells it extraordinarily well, in “Deep Down Dark: The Untold Stories of 33 Men Buried in a Chilean Mine, and the Miracle That Set Them Free.”

Tobar, a novelist (“The Barbarian Nurseries”) and a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, based the book on hundreds of hours of interviews that allow him to flesh out fully the men we glimpsed in news coverage, in flawed moments as well as heroic ones. The result reads like a thriller, even though we know the outcome.

Tobar begins before the disaster, in order to put the men in the context of their country and its economy. The San Jose copper mine, set in a remote, surreal desert landscape, has a long history of “cutting corners” and shoddy conditions.

Some of the miners travel as much as a thousand miles for a difficult, perilous seven-day shift. But their jobs pay well in a shaky economy, enough for many of them to own homes and send their kids to college, and they are proud, skilled workers.

Tobar's description of the mine's collapse and the men's dawning realization of their dire situation is breathtakingly, horrifyingly vivid. “A single block of diorite, as tall as a forty-five story building, has broken off from the rest of the mountain and is falling through the layers of the mine, knocking out entire sections of the Ramp and causing a chain reaction as the mountain above it collapses, too.”

What follows underground is 17 days when the men have no contact with the outside world and no idea whether they will ever be freed. When a drill bit crunches through the ceiling of the room called the Refuge where many of them are gathered, they bang madly on it with wrenches to signal their presence to the searchers on the surface. It's an exhilarating scene — but there are 52 days to go before they will see daylight.

Tobar skillfully tells the stories above ground as well, of the camp of families and other supporters at the mine, the corporate dodging and political wrangling, the intense efforts of the rescue team, which included advisers from NASA.

And he follows the men after their rescue, as they go to Disney World and the Holy Land, quarrel with and support each other. Some take money they receive and start their own businesses; others struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder. And some are back underground — not in the San Jose, which is shut down, but at other mines. One of them tells Tobar, “The first day, I felt a little strange.” But, he says, “The fourth day, I was starting to like it.”

“Deep Down Dark” turns an extraordinary story into an extraordinary book.