Critical Mass's new Second Thoughts series, curated by Daniel Akst, begins this week. More about this series, and how to submit, here.

I have a perfectly clear memory of reading the final chapters of Crime and Punishment. As with most memories, though, I’ve lost track of the facts—was I 15 or 16? Which English teacher assigned it?—and retained only the sensations. What I mostly remember is the way my bedroom looked.

That room was on the ground floor of a postwar Cape Cod cottage in suburban Maryland. It was a covetable piece of property within the house, larger than I needed and separate from the rooms of my mother and brother, which were upstairs. But any place where I spent my teenage years was bound to feel both confining and painfully exposed. I was bothered by the proximity of the kitchen and living room, which meant that any sounds I produced would be audible to my family. I didn’t like that the bathroom was across the hall, however convenient that might be, because I was always hearing footsteps passing by my door. The door itself presented a dilemma I was never able to resolve: If I locked it, then everyone would know (so I felt) that I was trying to hide something; if I didn’t lock it, then there was a chance someone might burst in.

And catch me at … what? My furtiveness had no basis in reason. I did almost nothing in those protracted after-school hours, certainly nothing that would have gotten me in trouble. But I lived in horror of being observed. I was constantly covering up for my most mundane activities, and then, because such behavior was odd and inexplicable, covering up for the cover-ups. Whole days would dissolve into the low white noise of sports talk radio. I remember how the late afternoon light would squeeze against the windows on either side of my bed and how the room would then grow dim, as though losing consciousness. I didn’t have my own television and this was before the Internet provided an easy anesthetic to the ache of unwanted time. I genuinely don’t know what I did with myself.

It’s probably not a surprise that so misanthropic and self-absorbed a character as Dostoyevsky’s Raskolnikov would have held me in thrall. I might not have nursed the same bitter preoccupations with murder (instead I tended to morosely daydream about terrible tragedies happening to me), but the cadaverous Saint Petersburg student’s resentment and self-pity, his simultaneous yearning for isolation from the world and his despair of being alone, struck a gloomy chord in the barren afternoons that I read his story.

And though I don’t remember this part, I must have connected with the tension that gives the novel its agitated energy: Raskolnikov’s fear of being discovered as a murderer coupled with his underlying yearning to reveal himself. I must have been especially sensitive to that conflict because the central condition of my life was that I felt that I was always lying, and that to be caught lying was horrible and to stop lying was unthinkable.

But whatever precisely I thought, I remember reading the last two or three hundred pages as though in a time warp, racing through the psychological cat-and-mouse of Porfiry Petrovich’s police interrogations, the drawn-out demise of Svidrigailov, and Raskolnikov’s cathartic final confession.

That climactic scene—the last before the epilogue—is brilliantly prolonged. Raskolnikov goes to the police station to turn himself in and learns that Svidrigailov, who might have testified against him, has committed suicide. In a daze he changes his mind and leaves, then turns around again. That brief fermata before the crescendo of the confession gathered my senses to the power of the moment. The sun had set and my bedside lamp painted the empty walls with yellow light. But instead of the usual dim awareness that another day had been dispatched, I felt that the room, in its painstaking scarcity and silence, had become a conduit for the book’s fearful, exhilarating message: Absolution was real. It was possible to escape the maze of deceptions and show your true self to the world. I did not know the story of Lazarus that Dostoyevsky took as his leitmotif, but I intuitively understood the concept of regeneration, and I would learn to guard its promise, however indistinct its contours, whenever I tried to envision my future.

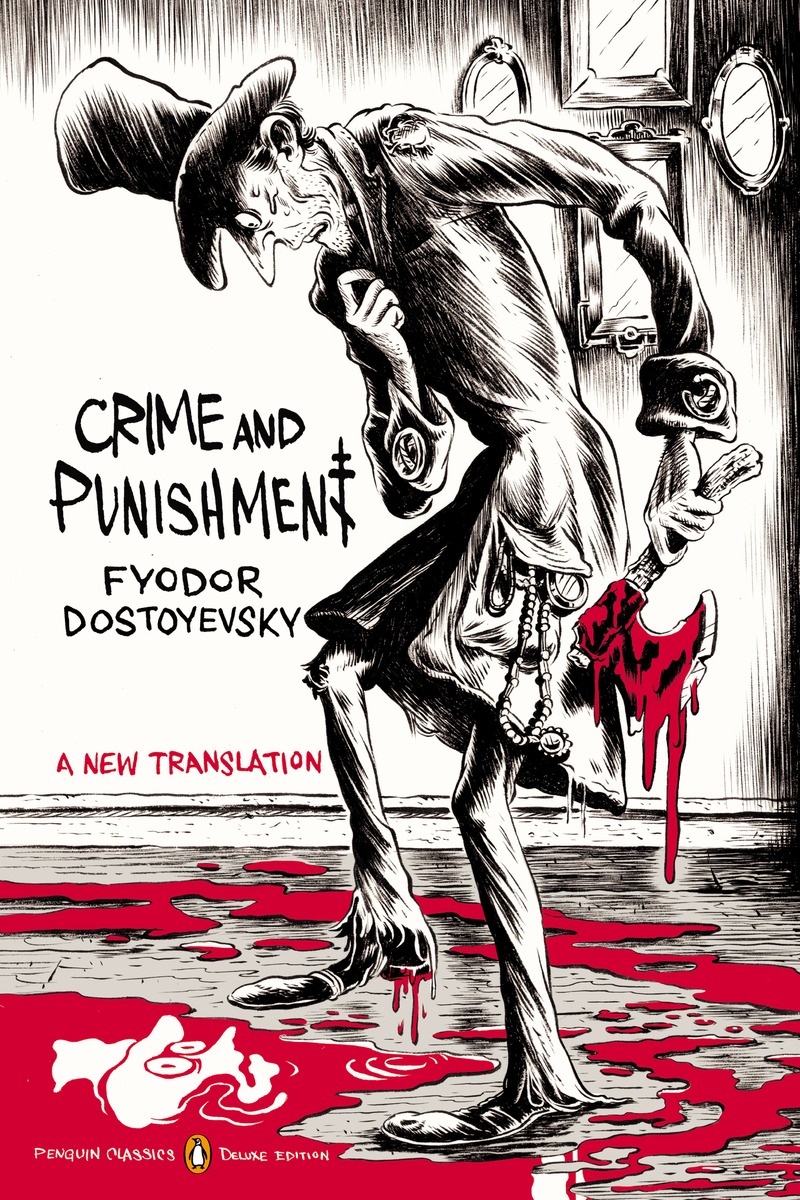

Some 20 years later, the watermark of that evening’s experience was still visible on the novel’s pages. Re-reading Crime and Punishment, as I recently did in Oliver Ready’s excellent new translation for Penguin Classics, I found that, just as the story was imprinted on my memory, I had projected my teenage self into the weft of the writing. Raskolnikov seemed to me almost excruciatingly adolescent.

There he is, skulking in his garret, rude and sullen, angrily shunning society yet continually overcome by a “thirst for human company.” The objects of his rage are the people who mean him the most kindness—his mother, his best friend, his poor unoffending girlfriend Sonia—and his response to their solicitude is to petulantly shriek, “Leave me alone!” He lies incessantly but he’s terrible at it, so in pathetic compensation he spends half the book in a state of willed delirium, like a middle schooler faking an illness to direct attention away from something he did wrong.

Even the killing of the pawnbrokers seemed, in this revisiting, to lack the gravity of existential horror—it just looked like a juvenile fit of pique. And what could be more cringingly familiar than the edifice of rationalization Raskolnikov goes on to build around his crime, propped up with a few creaking planks from Nietzsche and Hegel and buttressed by the vague, self-aggrandizing notion that misery and bad behavior are marks of misunderstood genius. “What does the word should have to do with it?” he complains in one of the endless philosophical bull sessions that fill the novel:

It’s not a matter of permitting something or forbidding something. Let him suffer, if he’s sorry for his victim … Suffering and pain are always mandatory for broad minds and deep hearts. Truly great people, it seems to me, should feel great sadness on this earth.

As an adult, I found myself unable to read such passages without rolling my eyes and muttering unkind oaths. This reaction shouldn’t be trusted, of course. I read Dostoyevsky’s Demons for the first time about five years ago, and though it’s also loaded with enough philosophical discourse to launch 1,000 dissertations, I found the book captivating. The difference was that I didn’t see my own face in it, as though I were really paging through an old high school yearbook.

I’ve found that this difficulty often arises when I revisit the touchstone books of my childhood. In those years, when I read, the membrane between the text and myself was utterly porous—I always assumed that the story was fundamentally about me. Later I would learn to read differently, to join emotional openness with intellectual distance and to search for the meaning of books within the (no less magical) context of their own creation. But for a long time, books existed simply as versions of my own personal fantasies. The books themselves, independent of my adolescent consciousness, may be irretrievable.

Alas, on my re-reading even the astonishing ending of Crime and Punishment was ruined for me. I’m not especially proud of the impatience and cynicism with which I greeted Raskolnikov’s confession. After all, I thought, it was Sonia who pushed him into revealing his crime. Forget spiritual rejuvenation—this was just a social misfit trying to impress his cute girlfriend. How mortifyingly typical!

Reluctantly, as I’ve organized these reflections, I’ve been able to recognize that the proof of the novel’s genius is its capacity to leave me unruffled. I’m venting about the book now to dispel the intense claustrophobia it evokes, claustrophobia that was once a way of life for me. Never have I been quite so scrupulously, prodigally unhappy as I was as a teenager, nor so receptive to visitations of euphoria and epiphany. It wasn’t an emotional state I wanted to sustain. For a little while, Crime and Punishment returned me to a familiar room I had been desperate to escape.