This is the sixth in Critical Mass's new Second Thoughts series, curated by Daniel Akst. More about this series, and how to submit, here.

This is the sixth in Critical Mass's new Second Thoughts series, curated by Daniel Akst. More about this series, and how to submit, here.

September 1989.

There is a heat wave in LA. I am 28 years old, eight months pregnant. I have just stopped working on my feet, as a cook and server for a caterer. With the exception of twice taking a dip in the pool of a friend’s apartment complex, I stay at home in front of a fan reading books. I don’t know how I heard about Mary Gaitskill’s Bad Behavior, which came out the year before. Maybe I read a review of it in the Village Voice, my hometown alt-weekly, or maybe in the LA Weekly, the paper of the city I moved to in 1986 to fulfill my destiny of becoming a movie star.

The movie star thing had not worked out. Nor had the writing thing, in New York, where I catered during the day and at night drank at an East Village bar with people I knew only from the bar, including a Ukrainian-American plumber named Angus who would feed me spleen sandwiches from a deli on First Avenue to help keep the booze down. I regularly fell asleep on the subway home to Brooklyn. In the morning I wrote in a desultory fashion. I did not know what I was doing and the goal of being a writer seemed both too distant and too bright to be mine, as well as a distraction from my constant preening before an imaginary camera.

The week before I quit the catering gig, I worked a party at a mansion in the Hollywood Hills. Cleaning up, walking along the edge of the blue-lit swimming pool, I was stopped by a guest. It was Quincy Jones. He asked me to bring him another Perrier. This tasted like failure and humiliation, and I might have given him a look that asked, does it give you special pleasure to ask an eight-month pregnant woman carrying a steam tray at midnight to serve you? I fetched the water.

Gaitskill’s stories turned out to be about failure and humiliation and other things that occupy and preoccupy a twenty-something city girl, or this twenty-something city girl. Her characters grew torpid on their impotence, crab-walked past their dreams. They were afflicted with the sense that real life was happening to others elsewhere, or had already happened to them but they had not been paying attention. They were starting to understand regret.

I lay down the book. Were people allowed to write this way? Gaitskill took the frustration that made me feel like a cat in a cage and fashioned it into a glass spike she used to stab her way out.

Spring 2006.

My daughter is 16. She and her girlfriends are asking for book recommendations. I give them Bad Behavior. They ask what it’s about. I tell them I cannot remember the stories, only that I loved them, that they alerted me to something I needed to know, and, while I could not have anticipated this, the author had given me permission to write. I have been a writer for 15 years, writing about serial killers and movie stars and cop bars and SRO hotels, about hope and delusion and fame and failure.

June 2015.

My daughter and I discuss the work she is doing as a photographer in New York and Los Angeles and, this past weekend, in a cheap motel in Las Vegas. We talk about the scenes she is capturing, spooky glimpses into other people’s life stories, as well as her own life; she does with her camera what I do as a writer. I mention how influential Bad Behavior was, how I was pregnant with her when I read it.

“It’s one of my favorite books,” she says.

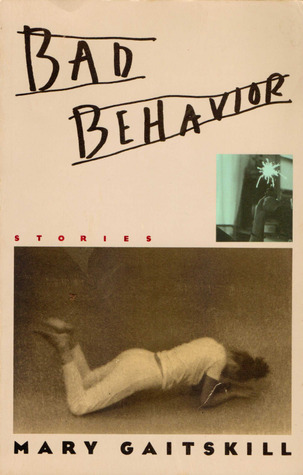

The original copy is on my shelf. I notice now what I did not before, how the cover perfectly captures what’s inside, a woman facedown on the floor, ready to submit but also to rise.

When I gave the book to three 16 year olds, I had not recalled the details of what the characters imposed on themselves, the commodity and weapon that is sex, the self-recrimination, the unearned knowingness that turns out to be wrong, the stasis and the mire. Reading the stories again, seeing the language precisely etched (something else Gaitskill did with her glass spike), it occurred to me that I gave the book to the girls in order to save them a step.

Nancy Rommelmann is the author of the story collection Transportation. Her book reviews appear in the Wall Street Journal and Newsday. She recently completed the nonfiction book To the Bridge, the story of Amanda Stott-Smith, who in 2009 dropped her two young children from a bridge in Portland, Ore. in the middle of the night.