This is the eighth in Critical Mass's new Second Thoughts series, curated by Daniel Akst. More about this series, and how to submit, here.

In a somewhat measured attempt to match the fine example of my 11th grade composition and literature teacher, Mr. Phelan, at Proviso East High, but faced with the clumsy imperfections common to the young and bookish, I had kept my promise to read more widely than the “required reading” list for our class. An effort, I came to see only later, to know broadly and deeply the lay of the land. A sounding or charting, of sorts—this running of eyes, fingers and minds over the words on a page, mapping the world in the process.

Mr. Phelan was a Sixties sensibility loosed without notice into the wayward halls of an otherwise dull and burdened institution. Young, tall, hipster cool in his sports jacket, tie, jeans and shoulder-length hair, he stood in marked opposition to the existing state of affairs. He was an intelligent, imaginative and engaging figure resolute in the belief we were capable of much greatness given the least bit of guidance and concern. He treated us as colleagues, respecting our judgments and insights as genuinely valid and significant. We quickly became quite possessive of him and began to think of him as our own. Who among us does not have a similar account of a teacher we loved and respected and who reinforced our sense of self during those early years?

For those with long memories, yes, this same Proviso East High, just outside Chicago, featured prominently in Jonathan Kozol’s Savage Inequalities.

I proudly read only fiction at the time. Letters, memoirs, biographies, and autobiographies were a bit too personal for my liking. Non-fiction seemed to me a complete betrayal of the lofty goals of Literature, so I shunned it, although History proved a worthwhile exception. Were I you I would not attach undue significance to such a view. It was more a state of mind than a fully reasoned critique. Pride found many ways of informing my young life: I was also proud of my hair, let my free flag fly; proudly wore those bell-bottom jeans; proud would prove insufficient when asked to accommodate my feelings for “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud”; prouder still, of Fred Hampton; still proud of the University of Chicago.

It was into this divide—between fact and fiction, the Black Power Movement and Integration, Literature and Life—that our Mr. Phelan set foot. He helped instill in me the desire to fill my head with words and books and the knowledge and wisdom of the worlds contained within them. Through him I encountered The Trial and The Castle, Crime and Punishment, For Whom the Bell Tolls, The Souls of Black Folk, The Sea of Fertility, Leaves of Grass, A Room of One’s Own, 1984, The Great Gatsby, and a dozen or so others during that extended year, summer included.

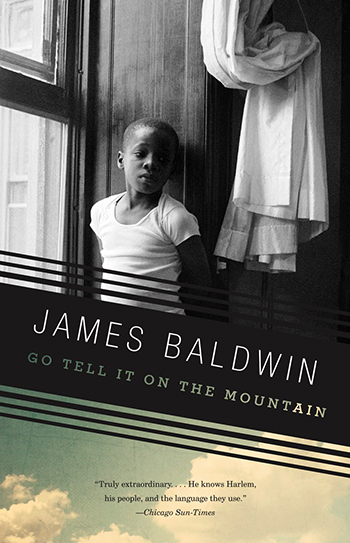

Then I read Go Tell It On The Mountain, James Baldwin’s examination of the human condition, recounting the Black experience in America through the lives of a church-centered Harlem family in the 1930s. These children of former slaves were part of the First Great Migration, which poured forth from the rural South between 1910 and 1930 in search of a better life, mostly in northern cities.

An ominous opening paragraph set the tone:

Everyone had always said that John would be a preacher when he grew up, just like his father. It had been said so often that John, without ever thinking about it, had come to believe it himself. Not until the morning of his fourteenth birthday did he really begin to think about it, and by then it was already too late.

When John awakens on that day he is confronted first by sin (“he has sinned with his hands a sin that was hard to forgive”) which he fears will damn him from eternal life in the world to come; and then by the uncompromising world of poverty and filth he has inherited from this life. In the deeply religious (and evocatively named) Grimes household it is easy to see how a young boy would imagine himself bound for Hell, especially given that his act was committed imagining male, not female, bodies.

The room was narrow and dirty; nothing could alter its dimensions, no labor could ever make it clean. Dirt was in the walls and the floorboards, and triumphed beneath the sink where roaches spawned; was in the fine ridges of the pots and pans, scoured daily, burnt black on the bottom, hanging above the stove;

And again

…Dirt was in every corner, angle, crevice of the monstrous stove, and lived behind it in delirious communion with the corrupted wall.

And further still

John thought with shame and horror, yet in angry hardness of heart: He who is filthy, let him be filthy still. Then he looked at his mother, … and the phrase turned against him like a two-edged sword, for was it not he, in his false pride and his evil imagination, who was filthy?

Baldwin pressed upon me the ugly, ugly truth; this dirt and filth extended far deeper than the walls and ceiling. It embodied the destruction, torment and wretchedness common to black life in America. It permeated every aspect of their existence. It settled on their skin and invaded their sleep. It robbed them of their dreams. They ate, slept, worked, dreamed and died, like all the unimaginable others, in this constructed reality designed precisely for them—owning nothing, possessing nothing, having dominion over nothing, not even themselves—endless numbers of jumbled and tangled lives counted for nothing as they unfold and recoil in this toxic miasma, their dull, leaden cry joined with the distant chatter of the universe.

At 17 I learned those truths. To say I did not deal with them well understates the matter and hangs uncomfortably on me. In plain fact, I behaved shamefully.

As Fannie Lou Hamer said, “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.” I was sick and tired of hearing and reading about the lives of Black people spent singing, moaning, praying and waiting, always praying and waiting, for deliverance from on high, of shattered dreams and broken bodies God-directed to their destruction, and plundered lives destined for hell-holes full of squalor and ignorance. I never wanted to hear another “John 3:16,” or “Hallelujah,” or “Praise the Lord,” coming from the mouth of a Black person for as long as I might live. Broadly, for fear that indiscriminate brush might taint me, and more directly because, as I had taken to heart the old guard’s unrelenting imperative, “learn your letters,” I discovered I was shadowed by the immense shame that I associated with the voiced lives of most of the Black people I knew.

Baldwin had shattered my idealized literary conceits and left them in a pile at my feet. Stopping squarely in front of me, he shoved me pointedly in the chest and suggested I had been living a lie. I had taken refuge in books that did not take me into account, that did not concern me or the lives of Black people in the least, while ignoring books like Baldwin’s. If that was the case, then I was hiding from the truth, not wanting to hear the truth; and he called me on it. Then stepping so close I could feel the force of his words and the heat of his breath on my face, he latched on to me with those troubling eyes and asked what was I going to do about it.

I grew angry. I stuttered and stammered and paced about, filled with a burning rage, a stinging indictment that began at the base of the neck and reached my ears before I was able to extinguish it. I groped here and there, I grasped at the air, clutched for anything at all, to catch my terrible, tumbling fall: a rope, a paddle, a hand basket.

Not prepared to face my shame or my fears, I wanted no part of him. I blinked…

Did you think love was just a chat at a small table?

Thick with breath and tobacco

smoke and endless talk *

Having hardened my own heart in much the same manner as John, I preferred to think of Go Tell It On The Mountain as more of the same, as the age old story that seemed to have characterized Black lives in writing since the beginning of time, Baldwin’s protestations aside.

Leaving Chicago for Los Angeles I needled together another 17 years before reading Mountain again. It was more than 20 before my latter day road-to-Damascus moment, when the falling away of the scales was fully complete.

In those intervening years I often consoled myself with the excuse, “I was17.” I had taken my personal battles—with Church, Language and Identity—out on him. I have since forgiven myself that indiscretion. Subsequent readings would show my displeasure lay decidedly within myself.

What was important later on, I think, was I simply let the work speak to me. I did not attempt to define it by my preconceptions or my personal motivations. Only then did I see language, lyric and poetic, bound to anger, rage and indignation and expressed with an eloquence that rivaled Henry James in its beauty and strength; see him track the universal in the personal, while opening the interior life of Blacks to the world; witness him, with directness, clarity and precision, strip away the façade of America’s hypocrisy routinely expressed through its disingenuous language.

What I found was, as Toni Morrison put it in her eulogy for Baldwin: “In your hands language was handsome again. In your hands we saw how it was meant to be: neither bloodless nor bloody, and yet alive.”

It’s hard to know how to repay a debt to a writer whom I’d steadfastly resisted and refused to hear, now that he no longer has need for what I would offer. Yet thanks to the very gift he gave me, the world is full of gratifying possibilities for doing so, this being only one.

Garry Howze is a freelance critic in Washington, DC. He is at work on a collection of essays, The Sun Would Soon Give Up the Struggle.

* Honor Moore (in her version of a line from Marina Tsvetaeva), “Poem for the End”