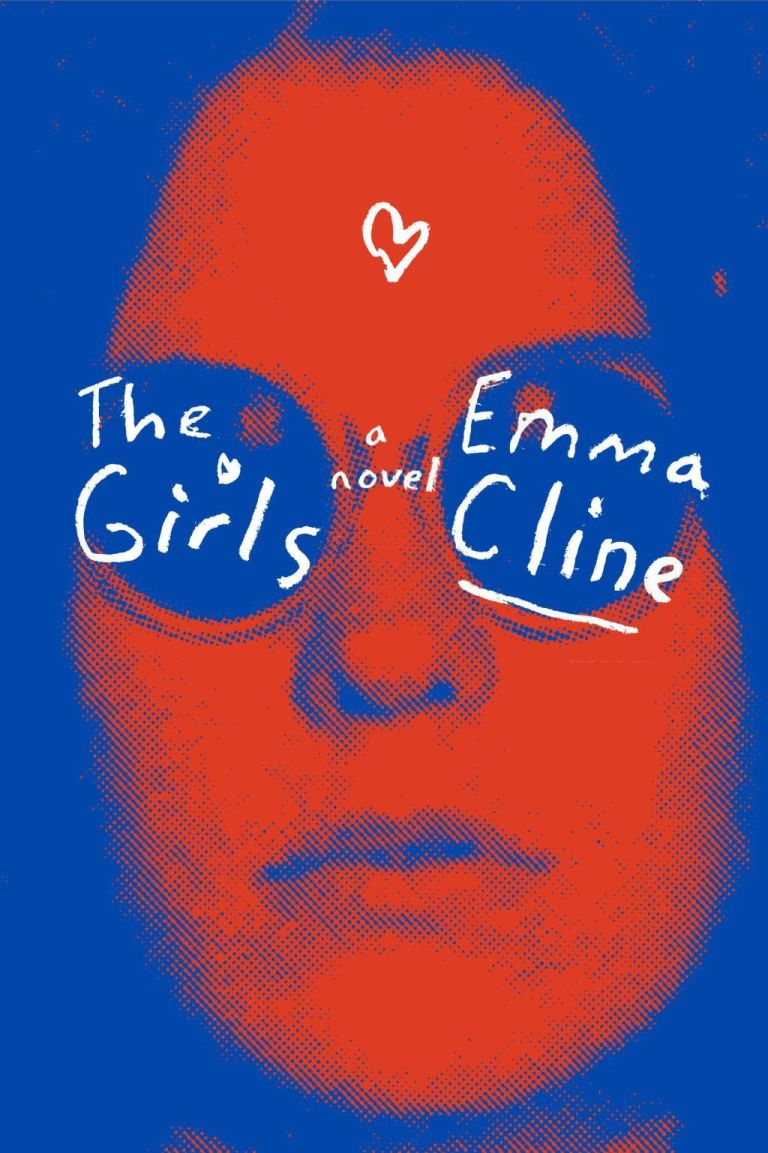

In November, National Book Critics Circle members will begin nominating and voting for the fourth John Leonard award for first book in any genre. In the run-up to the first round of voting, we'll be posting a series of #NBCCLeonard blog essays on promising first books. The third in our series is NBCC member Anita Felicelli on Emma Cline's The Girls (Random House).

In November, National Book Critics Circle members will begin nominating and voting for the fourth John Leonard award for first book in any genre. In the run-up to the first round of voting, we'll be posting a series of #NBCCLeonard blog essays on promising first books. The third in our series is NBCC member Anita Felicelli on Emma Cline's The Girls (Random House).

What makes Emma Cline's dark debut The Girls so intoxicating is her ability to render with precision the turbulent emotions and observations lying just beneath both ordinary and extraordinary events. She's the kind of writer who identifies an experience so perfectly—both its texture and it's core—that you realize the existence of an emotion you might not have realized was there lurking under the surface of your own life.

In her depiction of a Northern California girlhood tilting towards darkness, Cline takes a subject matter that has only relatively recently been given its critical due —the individual consciousness of a teenage girl. The Girls unearths within that terrain all the insight and verve of literature on topics considered loftier.

As a fourteen-year-old in 1969, Evie Boyd spots a group of older girls at a park in Petaluma “sleek and thoughtless as sharks breaching the water.” Evie appears to be middle-class and utterly ordinary, the granddaughter of a film actress and the daughter of parents recently divorced. The older girls are thrillingly different than her best friend Connie, of whom she says “I'd always liked her in a way I never had to think about, like the fact of my own hands.”

Black-haired Suzanne catches Evie's eye right away. Later on, she's captured in a photograph and described as “feral.” The physicality of Evie's interest in Suzanne is interesting. Although the connection seems primarily like an intense emotional attraction on Evie's part, it is also sexual desire.

We know that Evie isn't there on the night of the murders from the beginning. The older Evie tells us that right off the bat. However, Cline build suspense in the novel by showing Evie's gradual descent into the world of a cult leader's girls, first stealing toilet paper for Suzanne, and then stealing from her mother. It would be tempting to focus solely on Evie's own relentless, shapeless willingness to self-destruct, but Evie's crush on Suzanne isn't complete delusion. In a small gesture that seems cruel in the moment, Suzanne saves Evie from herself.

The Girls is often described in connection with its mirroring of certain aspects of the Charles Manson murders. Perhaps this is because the connection to Manson is the commercial hook of a book that is unabashedly, luxuriously literary in its style. The Girls features a cult leader, Russell, whose inclination towards immediately urging his girls towards fellatio is apparently patterned after Manson.

Another writer might have mined the relationship between Suzanne and Russell, the cult leader. But what makes The Girls so fascinating and rich is not it's tackling of an American crime, but its exploration of the wild emotional attraction girls, especially those of a certain age, have to other girls. Unlike heterosexual crushes, a young girl's emotional same-sex crush doesn't follow any particular social conventions, and has nothing to bound it or define it or restrict it. The lack of language is also a lack of norms, and it leaves an absence that can be filled with greater darkness, perhaps, than relationships that have been more carefully coded and circumscribed for social order.

In adolescence especially, the allure of danger is conflated with connection. Years after her friendship with Suzanne, Evie notes, “I wished I'd stayed safely in my bedroom in the dry hills near Petaluma, the bookshelves packed tight with the gold-foil spines of my childhood favorites. And I did wish that. But some nights, unable to sleep, I peeled an apple slowly at the sink, letting the curl lengthen under the glint of the knife. The house dark around me. Sometimes it didn't feel like regret. It felt like a missing.”

Older Evie is a live-in aide, in between jobs, staying at an old boyfriend's house when the old boyfriend's son Julian and his girlfriend Sasha show up. Sasha is as formless and susceptible to influence as Evie was. Or so Evie imagines.

While this contemporary storyline may seem slight and inconsequential, in it there is the timelessness of a younger woman's needy, but almost parasitic relationship with an older woman she hopes to be, that one day she will fear she's become—that nicely dovetails with the primary story of Evie's crush on Suzanne. I was reminded of the final scene of All About Eve when, on the night of Eve's triumph and her undoing, a young anonymous woman holds up the Sarah Siddons award and apes Eve, bowing at herself in the mirror, an audience of one.

The brilliance of The Girls occurs sentence to sentence. The language is never merely pretty or showy, but derives most of its dazzling beauty from its willingness to provide a language for what is so often left unspoken. The Girls articulates the emptiness and desperate longing for connection that might allow a young woman who is well-off, but feels herself to be mediocre and ordinary under the male gaze, to follow another woman into darkness and depravity.

What does the young object of the male gaze look at? Men sometimes, but perhaps just as often at the slightly older version of herself, at what she might soon become.

Anita Felicelli is a writer whose nonfiction has appeared in the New York Times, Salon, San Francisco Chronicle, Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Rumpus. She lives in Northern California, where she's working on a short story collection and a novel.