In November, National Book Critics Circle members will begin nominating and voting for the fourth John Leonard award for first book in any genre. In the run-up to the first round of voting, we'll be posting a series of #NBCCLeonard blog essays on promising first books. The eleventh in our series is NBCC member Michael Magras on Stephanie Danler’s Sweetbitter (Knopf).

In November, National Book Critics Circle members will begin nominating and voting for the fourth John Leonard award for first book in any genre. In the run-up to the first round of voting, we'll be posting a series of #NBCCLeonard blog essays on promising first books. The eleventh in our series is NBCC member Michael Magras on Stephanie Danler’s Sweetbitter (Knopf).

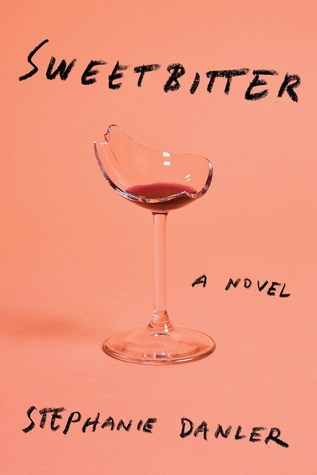

For anyone who has ever suspected that the backroom activities of the staff at a posh restaurant are far juicier than the refinement on display in the dining room, Sweetbitter, Stephanie Danler’s delightfully profane debut novel, is your validation. Danler, who worked in the restaurant business, has written a spicy-greens work of fiction: seemingly mild at first, but with a wit that grows more piquant over time.

It’s June 2006. A 22-year-old English major named Tess arrives in New York City from her home in the Midwest. She’s happy to have exchanged “the claustrophobic noise of the cicadas” and small-town America’s “twin pillars of football and church” for a more exciting life. The first stop in that new life, after renting a $700-a-month bedroom in a Williamsburg, Brooklyn apartment, is an interview at a fancy Union Square café. She can name only one of the “five noble grapes of Bordeaux”—a lucky guess—but the general manager hires her, anyway, after she tells him that, when she worked at a coffee shop back home, a diabetic customer stopped coming to the shop after her foot was amputated, and Tess would deliver scrambled eggs to the woman’s dog.

The restaurant owner tells her that she is a “fifty-one percenter,” that rare employee who has the intelligence, integrity, and self-awareness required for greatness. He’s right: Soon, the novice who had never heard the term cru learns that a Chardonnay is over-oaked if it’s vanilla and buttery, can distinguish a chanterelle from the smell alone, masters the crease-turn-crease-fan technique for folding linen napkins, and knows that, when you open wine at a table, you hold the bottle so that the guest—never refer to them as customers—can see the label.

One of the many pleasures of Sweetbitter is that Danler has written pitch-perfect backstories for each of the many staff members, most of whom snort drugs, smoke joints, gossip, and bandy the most creative of profanities. Will, one of the young “sergeants” who trains her, has created a Claymation version of Godard’s À bout de souffle and is now writing a feature film. Ariel, a dining room back waiter, tells Tess that she stole two Hallmark cards before she turned six, addressing one to John Lennon and one to her missing mother, and praying that they’d come to her party—a moot point, as it turned out, because her father forgot her birthday.

There’s the Chef who demands that no one but the owner speak to him while he prepares his masterworks in the kitchen. Jake, the bartender with whom Tess is smitten, has worked as a musician, a poet, and a carpenter, and is rumored to be a drunk and bisexual. In one of the novel’s many spot-on descriptions, Danler tells us that Jake “knew part of his job was to be looked at” and had “a stillness that made one want to paint him.” Tess isn’t the only one to have noticed him: Simone, a middle-aged woman who is one of the restaurant’s senior servers and can tell a wine’s vintage just by sipping it, has a complicated relationship with him. She and Jake “were not a couple, though their magnetic, unconscious way of tracking one another seemed to indicate otherwise.” What else can Tess conclude after she walks in on them in a back room of the restaurant and sees Jake with his trousers off? The closest this episodic novel comes to a story arc is the competition of sorts that Simone and Tess wage for Jake’s affections.

But plot is not the reason to read Sweetbitter. The joy is in its storytelling audacity, from stream of consciousness passages and long stretches of unattributed dialogue to the bracing juxtaposition of wait staff who do lines of coke in the bathroom of a bar yet treat a 90-year-old customer kindly when she wants to know when she will receive the soup she finished ten minutes earlier.

Any cook will tell you that, to prepare delicious meals, you start by choosing the best ingredients. But you still have to combine them with skill if you don’t want to end up with an unpalatable mess. With Sweetbitter, Stephanie Danler demonstrates the same dexterity. One assumes that her time in the restaurant business provided the book’s components. But to whip up a concoction this good, you need to know how to put them together. You need to be a fifty-one percenter.

Michael Magras is a freelance book critic. His reviews have appeared in the Minneapolis Star Tribune, Houston Chronicle, San Francisco Chronicle, Chicago Tribune, Philadelphia Inquirer, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Miami Herald, Los Angeles Review of Books, Iowa Review, and BookPage.