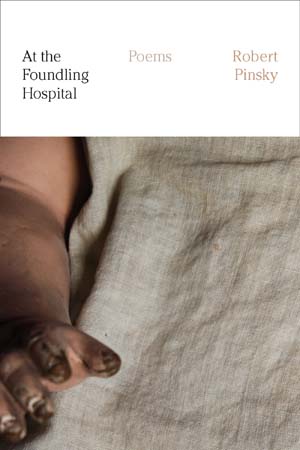

In the 30 Books in 30 Days series leading up to the March 16 announcement of the 2016 National Book Critics Circle award winners, NBCC board members review the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member David Biespiel offers an appreciation of poetry finalist Robert Pinsky’s At the Foundling Hospital (Farrar, Straus and Giroux )

In the 30 Books in 30 Days series leading up to the March 16 announcement of the 2016 National Book Critics Circle award winners, NBCC board members review the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member David Biespiel offers an appreciation of poetry finalist Robert Pinsky’s At the Foundling Hospital (Farrar, Straus and Giroux )

The Foundling Hospital, Robert Pinsky’s compressed, resonant collection — part treatise on mixed registers of high and low language, part menagerie of narratives, part ceremony of names and songs, part documentary on improvisation and the lyric — is built around an archive of nimble, historical, and private evocations.

The poems explore. And by explore I mean they inspect, probe, and research; they draw from their materials, whether it’s an instrument, a name, a token, a haftorah portion, a city, a dream, a robot, or a language; and they complement those unearthed things with an enduring retrospection that comes from clear thinking, narrative directness, integrity, and a feel for the percussive incantation.

Pinsky’s juxtaposition of private life and the public life retell a familiar, essential story of the capacity to recognize how one’s lone struggle to comprehend experience is often resisted by one’s inability to unify all the particulars. I want to say this has been Pinsky’s concern for decades, in essence to speak in a poem in an idiom that is contemporary while also to compose and fashion a poem that evokes and relies on the traditions of the art.

To illustrate: The central idea in this book, the one that makes the book immediate, if not essential, is, first, that the story of life is both the life and the telling of the life and, second, that the story of life is both the telling of the life and the interpretation of the life. Here are select lines and phrases from across the poems that illustrate these ideas —

Sweet vibration of / Mind, mind, mind… (“Instrument”)

I’m tired of the gods, I’m pious about the ancestors… (“Creole”)

Found and to find… (“Names”)

Fragment of a tune or a rhyme or name / Mumbled from memory… (“The Foundling Tokens”)

I drank the shadows, I studied the shell… (“Genesis”)

…the person still makes / A shape distinct and present in the mind… (“Grief”)

Aspiring, beset by failures… (“Dream Machine”)

I see you… / Completely. Naked. I’ve got you in my pocket… (“Improvisations on Yiddish”)

At the end of the story, / When the plague has arrived, / The performance can begin… (“Ceremony”)

…Stubborn little light, as if / Hammered from living rock / I quarried out of myself — / Not much, maybe, but mine / Down to the bone… (“Light”)

I could go on. There is a great warmth and benevolence in these lines. Like the blues, they are evocations of marrow and truth but also a protest against them. They hold a generosity that acknowledges the role that an allusive — and also elusive — past, present, and future offer to a poet, even as Pinsky unfurls his resignation about the brevity of life.

Pinsky says that the “unforgivable days…open and close / One after another and swallow up the years.” If that suggests a not-so-feel-good rendition about aging, life entering its most reflective stage, time running out, then it’s one that leaks hope. Because: through hope comes a recollection of the forgotten, and through recollection of the forgotten comes affirmation of the pleasures of meaning and pleasures of living that persist. To read Robert Pinsky is to stay true to the smallest details, to the sensual and social landscapes, and to the montage of private dreams and public history.