In November, National Book Critics Circle members will begin nominating and voting for the John Leonard award for the first book in any genre that has been published in the US in 2017. In the run-up to the first round of voting, we'll be posting a series of #NBCCLeonard reviews on promising first books.

The John Leonard Prize is our annual award based on member nominations and chosen by a panel of member volunteers. Named for the longtime critic and NBCC co-founder, John Leonard, the prize is awarded for the best first book in any genre. Previous winners include: Anthony Marra’s A Constellation of Vital Phenomena (2013), Phil Klay's Redeployment (2014), Kristin Valdez Quade’s Night at the Fiestas (2015), and Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing (2016).

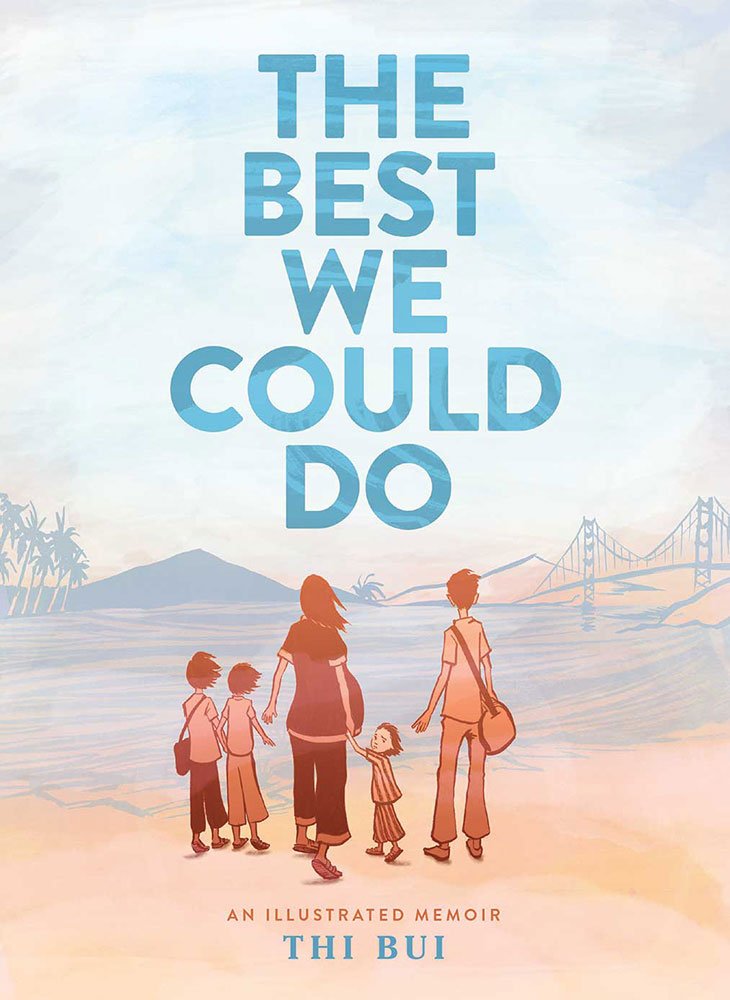

Our first in the series is The Best We Could Do by Thi Bui. (Harry N. Abrams). This review was originally published in the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

Thi Bui’s graphic novel about her family’s exodus from Vietnam begins in New York, where she is giving birth to her son—a tiny, jaundiced mite who has a “faraway face with old man eyes.” Over the next few days, as she struggles to breast-feed and care for the newborn, “a terrifying thought creeps into my head,” Bui writes. “Family is now something I have created.”

Thi Bui’s graphic novel about her family’s exodus from Vietnam begins in New York, where she is giving birth to her son—a tiny, jaundiced mite who has a “faraway face with old man eyes.” Over the next few days, as she struggles to breast-feed and care for the newborn, “a terrifying thought creeps into my head,” Bui writes. “Family is now something I have created.”

And family — complicated, difficult, sometimes tragic family — is at the heart of this intense and moving memoir. Bui is the narrator and only occasionally a character in the book, which focuses on her parents — their upbringing in Vietnam, their escape to the United States, their difficult life here.

We learn a sweeping, terrible history — the French occupation, the war, the stark division of the country, the rising power of the Communists, the brutality of the regime, the dangerous exodus of citizens — but always she brings it back to an intimate level. Politics are skimmed over; what is important are the bewildered people, trying to survive as their world changes and threatens them.

“I keep looking toward the past,” Bui writes, “tracing our journey in reverse, over the ocean, through the war, seeking an origin story that will set everything right.”

The details she records are unforgettable: a famished mother and son devouring a bit of sausage. A boy hiding underwater from soldiers until he nearly drowns. The starved dead piled up in handcarts to be hauled away.

Bui recounts how her father grew up impoverished in the countryside, with moments of joy punctuated by hunger and fear. Bui’s mother, Má, came from wealth but had a mother who was imperious and ice-cold.

“I hated it when my mother hit the servants,” Má recalls. “But she hit her children, too. We were all terrified of her.”

In well-chosen words and black-and-white drawings splashed with a fiery orange wash, Thi Bui (pronounced TEE BOO-ee) tells this fierce story. As the book unfolds, she begins to see her parents in a new light, as people who have endured unimaginable hardship and are doing the best they can. And yet the story is devoid of sentimentality.

Memoir is a fast-morphing genre, nearly as elastic in form as the novel. Memoirs are told in photographs and in poems, in chronological narratives and in text that meanders in time and place. Poet Eileen Myles’ new memoir, “Afterglow,” is told partly by her dog (her dead dog).

Memoirs told in comic book style, such as this one, are growing more popular. But Bui’s is the most moving I’ve seen this year: passionate, intimate, tackling huge themes — love, war, history, emigration — while focused intensely on one family.

If you want to better understand the history and scope of the Vietnam War, if you want to understand what immigrants have endured, and continue to endure, you can start with no better book.

Laurie Hertzel is the senior editor for books at the Minneapolis Star Tribune and NBCC Board member.