In November, National Book Critics Circle members will begin nominating and voting for the John Leonard award for the first book in any genre that has been published in the US in 2017. In the run-up to the first round of voting, we'll be posting a series of #NBCCLeonard reviews on promising first books.

The John Leonard Prize is our annual award based on member nominations and chosen by a panel of member volunteers. Named for the longtime critic and NBCC co-founder, John Leonard, the prize is awarded for the best first book in any genre. Previous winners include: Anthony Marra’s A Constellation of Vital Phenomena (2013), Phil Klay's Redeployment (2014), Kristin Valdez Quade’s Night at the Fiestas (2015), and Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing (2016).

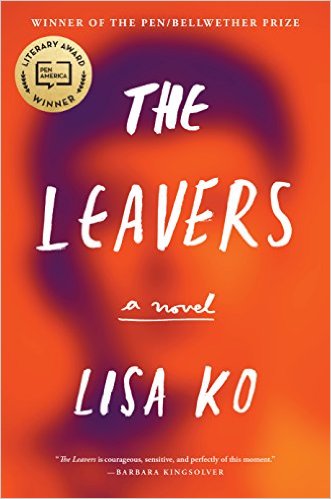

The Leavers by Lisa Ko. (Algonquin Books). Review by Lanie Tankard, originally published in The Woven Tale Press.

The Leavers by Lisa Ko. (Algonquin Books). Review by Lanie Tankard, originally published in The Woven Tale Press.

Who am I? And how do I know that? Such questions beat at the heart of Lisa Ko’s debut novel The Leavers, a well-timed tale set in the United States and China.

The structure is a mother-son story—two mothers, two families, two cultures. Polly (formerly Peilan) Guo has an eleven-year-old son named Deming, conceived in China and born in America. An undocumented immigrant in New York City from a small Chinese fishing village, she works first at a jeans factory then a nail salon. When Deming was a baby, she sent him to live with her father because she could neither take him to work nor afford childcare. Deming thus spent some of his formative years with his grandfather in Minjiang (“a poor village in a poor province”)—apparently a fictional place near the Min River in the southeastern China province of Fujian, of which the city of Fuzhou is the capital.

With a few years under his belt, Deming returns to his mother in the Bronx, where they live with her boyfriend Leon, as well as Leon’s sister and nephew (Deming’s pal Michael). The family they’ve forged together lives austerely but provides a cushion for the slings and arrows of a different culture, such as a clerk smirking at Polly’s “lousy English.”

One morning, however, Deming’s known world suddenly spins out of control when his mother doesn’t come home from work and no one seems to know what happened to her. He ends up in the social welfare system and is eventually adopted by a childless couple—white academics from Ridgeborough, a fictional small town in upstate New York near Syracuse, where Deming is the only Asian. His new parents (Kay and Peter Wilkinson) erase his Chinese name. No longer Deming Guo, he must become Daniel Wilkinson. The lone vestige of his former life is his mother’s button stuffed deep in his pocket.

For the remainder of the novel, readers move backward and forward—past, present, and future—following Deming/Daniel as he searches for Peilan/Polly to understand why his mother left him. Along the way, Ko unflinchingly confronts a number of flinchworthy situations through a powerful lens. The book has four sections: “Another Boy, Another Planet,” “Jackpot,” “TILT,” and “The Leavers.”

Much recent world fiction concerns refugees assimilating into new cultural identities. Ko delves deeply into that struggle here. Language is one aspect. Because Deming and Polly speak Fuzhounese—which Ko underscores is not the same as speaking Mandarin at all—they face yet another language barrier apart from English, not only in America but also in China. In the Big Apple, Deming hears “everywhere the indecipherable clatter of English.” In Ridgeborough, he finds “the crumbs of dialect…washed out to sea…” because “New York City had provided him with an arsenal of new words.” When he goes back to China, to Fuzhou, he notices “not one scrap of English, not anywhere.” Instead, “Fuzhounese and Mandarin banged out around him.”

Some researchers study the relationship between language and thought, such as variations in time conception between Mandarin and English speakers. The recent movie Arrival was based on the novella “Story of Your Life,” penned by an American science fiction writer whose parents emigrated from China. Other researchers look at the relationship between culture and identity formation, establishing dissimilarities between East and West. One project found variations even within China itself, based on agriculture.

How does research relate to The Leavers? It offers a framework by which Ko presents concrete examples of how findings play out in two countries on opposite sides of the globe, cities of differing sizes, various age groups, and professions all along the skill range. The Leavers probes not only language, but also cultural relativism and ethnocentrism.

Ko illustrates individualist (independent) and collectivist (interdependent) behaviors with astute observations, suggesting how one culture views another—and, of equal importance, how each perceives being viewed by the other. Consider, for example, dwelling sizes and anonymity. In the Bronx: “They lived in a small apartment in a big building, and Deming’s mother wanted a house with more rooms.” He, however, enjoys the potpourri of cultures: “This building contained an entire town.” In Ridgeborough, the Wilkinson house is “five times” the size of that apartment, and “seven times the size of the house” where he’d lived with his grandfather in Minjiang. He finds himself “too visible and invisible at the same time,” realizing he “had never known how exhausting it was to be conspicuous.”

Yet he’s “not that unhappy” with the Wilkinsons—if he can forget about his mother. That’s not possible though. “Like muscle memory, a body could recall things on a hidden, cellular level,” Ko writes, much as Homer portrayed Odysseus in The Odyssey: “His native home deep imag’d in his soul.” Odysseus’s mother, Anticlea, actually died of a broken heart she missed him so much: “…my longing to know what you were doing and the force of my affection for you—this it was that was the death of me” she tells her son when he visits her in the Underworld. Another recent movie, Lion, as based on the book A Long Way Home about a son’s twenty-five-year search for his mother back in India after being adopted by a couple in Australia.

Deming/Daniel loves music, and wants to play in a band. He desperately wants Polly there to tell him who he should be, since he’s not sure Kay and Peter Wilkinson’s idea of success is the same as his. Whose definition of achievement counts? Would his mother even understand him as an adult if he found her? She had known him only as a child when she left.

To adapt is to alter, rework what’s there. In the act of becoming part of something, one must modify to suit the environment. Can changing a name suddenly transform the person? Are Polly and Peilan two people inhabiting the same body? As Deming tries to become Daniel, he morphs into “a name that was supposed to be his.” So, is Deming Chinese and Daniel American then? Who gets to define someone? The hazy image of Deming/Daniel on the book’s cover emphasizes his identity crisis. A person might look the same but what’s inside is radically different, not the same at all. To feel at home is to belong. You blend in when you’re in one society—yet in another, you’re no longer anonymous.

What is home? James Baldwin, in Giovanni’s Room, speculated: “He made me think of home—perhaps home is not a place but rather an irrevocable condition.” Baldwin’s notion of home might be what Ko is suggesting in The Leavers. She forces the reader to consider what it’s like to have always spoken one language, kept your original name, and known where your mother is—and then try to appreciate the opposite. She runs “they don’t belong here” up the flagpole to watch it flap in the wind. She asks what being a mother means. She pores over the definition of a leaver—someone who departs, but in so doing causes something to remain. Ko pluralizes the title of her novel, using “Leavers” instead of “Leaver,” because Polly is not the only leaver in this story. Many characters leave a considerable number of times over the course of the novel, and many are left behind in countless ways.

Ko is a master at interlacing current political and social issues throughout her storyline, which is specific to her protagonists but also broader in its universal subjects: immigration, deportation, incarceration, for-profit detention centers, adoption, adaptation, mothering, gentrification, garment factories in New York, manufacturing in China, nail salons, slaughterhouses, gambling addiction, diversity, academia, ethnic studies, women’s roles and rights, assertiveness, marriages of convenience—to name but a few. She stages this underlying set of ideas in both countries and across the entire lives of her protagonists as if she were using a 360-degree virtual reality camera that could span the globe as well as time travel.

Ko echoes and modernizes some of Pearl S. Buck’s impressions about East and West, such as this image from Buck’s long-lost novel, The Eternal Wonder, “Crowds moved wherever he went, across the bridge to Manhattan, in New York, wherever he went, life flowed and eddied, but he was not part of it.” Or this thought from East Wind: West Wind—The Sage of a Chinese Family: “He will have his own world to make. Being of neither East nor West purely, he will be rejected of each, for none will understand him. But I think if he has the strength of both his parents, he will understand both worlds, and so overcome.”

For an epigram to jumpstart The Leavers, Ko selected an inspired verse from a poem by Li-Young Lee that mentions orphaning, aliases, journeys, and expulsions—a relevant entry to the prevailing power of memories she presents within. The novel is well worth reading for the story by itself, but even more so for the combustible discussion it’s bound to spark. Lisa Ko herself becomes a leaver here, depositing at book’s end a trail of potent thoughts challenging readers—nay, shaking them by the shoulders—to consider the issues she raised. For this reason alone, The Leavers is de rigueur in the current Zeitgeist.

Lanie Tankard is the Indie Book Reviews Editor for The Woven Tale Press