What's your favorite work in translation? That's the question that launches this summer's NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of NBCC members and honorees. (Previous NBCC Reads series dating back to 2007 here.) Tell us why you love the book (in 500 words or less) be it a new one, like Sayaka Murata’s quirky little novel, Convenience Store Woman, or something a bit older, such as Stefan Zweig’s evocative memoir, The World of Yesterday. The deadline is August 3, 2018. Please email your submission to NBCC Board member Lori Feathers: lori@interabangbooks.com

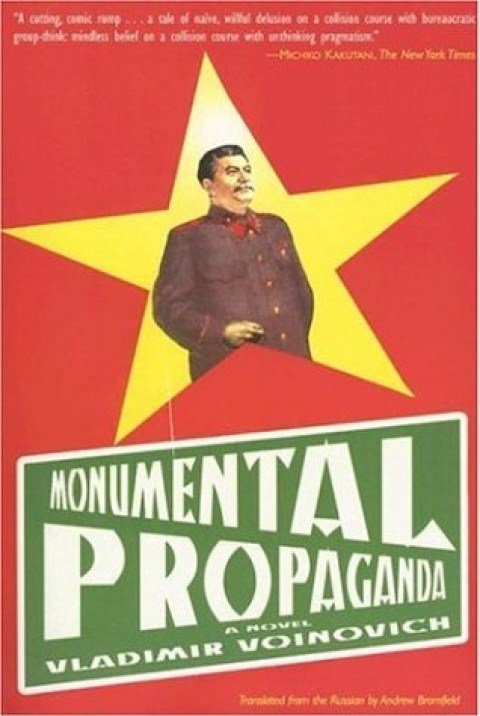

For personal and political reasons, I’ve been thinking about satirical novel Monumental Propaganda, translated from the Russian by Andrew Bromfield (Knopf, 2004). Voinovich was a dissident writer for decades in the USSR, but this acerbic novel was published long after the fall of the Soviet empire. It’s about a poor, unrepentant Stalinist named Aglaya, who’s determined to keep the glory of the gulag alive even when Khrushchev admits that mistakes were made. In a determined show of reverence, she drags a cast-iron statue of “our own dearest beloved Comrade Stalin” from the scrap heap and sets it up in her apartment. With this absurd and self-righteous character, Voinovich brilliantly

skewers our desire to ignore the lessons of history and romanticize our political monsters.

Like any great satire, Monumental Propaganda feels perennially relevant. Under Putin, Russia has grown only more nostalgic for totalitarianism since the novel was published. And for American readers, Aglaya’s resolve to maintain a statue of Stalin speaks directly to our lingering affection for memorials to the traitors who took up arms against the United States during the Civil War. Last summer President Trump mourned “the removal of our beautiful statues and monuments,” as though American culture would somehow be diminished if we didn’t honor the defenders of mass kidnapping, torture and rape.

But for all the fun Voinovich has with Aglaya and her statue worship, Monumental Propaganda is also a satire of the invertebrate party leaders and townspeople who oppose her. They all demonstrate a remarkable degree of ideological flexibility — an expedient willingness to change their principles for political gain. (See: Washington.)

I have a personal reason to treasure this novel, too. When I applied to work at The Washington Post back in 2005, I’d recently praised Monumental Propaganda in the pages of The Christian Science Monitor. As it happened, two of the people who interviewed me, Robert Kaiser and Marie Arana, were big fans of Vladimir Voinovich.

I keep a little statue of him in my house.