What are your favorite works in translation? That's the question that launches this summer's NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of NBCC members and honorees. (Previous NBCC Reads series dating back to 2007 here.) Tell us why you love the book (in 500 words or less) be it a new one, like Sayaka Murata’s quirky little novel, Convenience Store Woman, or something a bit older, such as Stefan Zweig’s evocative memoir, The World of Yesterday. The deadline is August 3, 2018. Please email your submission to NBCC Board member Lori Feathers: lori@interabangbooks.com

Why are we not all reading Natsume Soseki?

A few years ago I was introduced to his best-known novel, Kokoro, by a professor of Japanese literature at Berkeley. It was terrific, and I was grateful, though not so grateful as to immediately seek out more of Soseki’s novels. I can’t explain why, except that the experience of reading that one was completely satisfying in itself, and also sufficiently odd (Soseki is a master of tiny gestures and inconclusive endings) that I didn’t feel the experience could be duplicated.

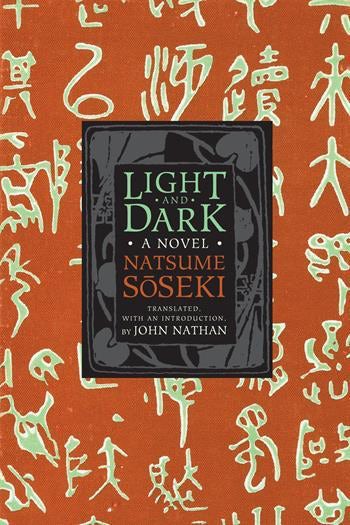

More recently, however, Columbia University Press issued Light and Dark, his final, unfinished novel—he died when he was in the midst of publishing it serially, in 1916—and surely his masterpiece. Because of Soseki’s habitual inconclusiveness, the unfinished bit doesn’t matter that much: it is not like being dropped cold at the abrupt termination of Edwin Drood, but more like being let down gently at the end of a Chekhov story. Yet the Russian writer whom Soseki most closely resembles here is not Chekhov, but Dostoyevsky. Like Dostoyevsky (and like Jane Austen, whom Soseki apparently loved), he has learned how to create obnoxious characters that grab you by the throat and won’t let go. Like Dostoyevsky (and also like Henry James, another English-language influence on Soseki), he can stretch every emotional confrontation between two people into a seemingly endless encounter, a psychological endurance test for readers and characters alike. Yet unlike these more familiar writers, he does so in the startlingly modern context of early-twentieth-century Japan, against a background in which Freud, Cubism, and revolutionary politics vaguely figure. The novel explores the young married life of a couple named Tsuda and O-Nobu, each of whom is self-centered and somewhat despicable but also strangely sympathetic, even—or especially—when they find themselves at odds with each other. It is something like Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage, but without the excessive melodrama, and with far more interiority on the part of the two main characters. I have never read another book like it, and I don’t expect I ever will, but it has made me a Soseki convert for life.