What are your favorite works in translation? That's the question that launches this summer's NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of NBCC members and honorees. (Previous NBCC Reads series dating back to 2007 here.) Tell us why you love the book (in 500 words or less) be it a new one, like Sayaka Murata’s quirky little novel, 'Convenience Store Woman,' or something a bit older, such as Stefan Zweig’s evocative memoir, 'The World of Yesterday.' The deadline is August 3, 2018. Please email your submission to NBCC Board member Lori Feathers: lori@interabangbooks.com

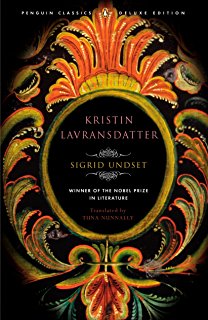

Many years ago I picked up a translation from the 1920s of “Kristin Lavransdatter,” a trilogy by the Norwegian writer, Sigrid Undset—but I couldn't take its dishearteningly affected prose. The first character to open her mouth set the tone: “Methought I must needs have a sight of her. But you must take the cap from her head; they say she hath such bonny hair.” Set in 14th-century Norway, the story continued in a relentlessly faux archaic manner until I finally bailed out at “within the house all spoke of well-being, and the customs of the house were seemly, following the ways of great folks' houses in the South.”

After a period of recovery, I tried Tiina Nunnally’s more recent translation, where, in a note she explains that the earlier English translators had, in fact, imposed the archaic style I found so off-putting. Compare Nunnally's rendition of the passages quoted above. In her hands, the novel's first speaker says, “I thought I'd have a look at her. You must take off her cap. They say she has such fair hair.” And the next passage takes an equally forthright approach: “Inside the buildings everything looked prosperous, and the customs of the house were as courtly as those of the gentry in the south of the country.” Gone is all that mildewed bombazine; restored are cleanliness and simplicity. And revealed to me at last was an astonishing work of psychological complexity: the 1,124-page story of a 14th-century woman's journey through “the perilous and beautiful world.”

The scenes of nature, in its cold, northern immensity, are terrifying and exhilarating, and intrinsic to the fierce Scandinavian soul potently etched in this novel: “For those who were waiting for the redemption of spring, it seemed as if it would never come. The days grew long and bright, and the valley lay in a haze of thawing snow while the sun shone. But frost was still in the air, and the heat had no power. At night it froze hard; great cracking sounds came from the ice, a rumbling issued from the mountains, and the wolves howled and the foxes yipped all the way down in the village, as if it were midwinter. . . . Kristin went out on such a day, when the water was trickling in the furrows of the road and the snow glistened like silver across the fields. Facing the sun, the snowdrifts had become hollowed out so that the delicate ice lattice of the crusted snow broke with the gentle ring of silver when she pressed her foot against it. But wherever there was the slightest shadow, the air was sharp with frost and the snow was hard.”

As in the natural world portrayed here with such brilliance, the life depicted in these pages is one in which opposites have abrupt proximity, reverses occur quite suddenly: love turns to hate, joy to guilt, freedom to bondage, present to past, life to death. The tension between the contrasting demands of society and individual desire surges through the novel. The story twists and turns and doubles back, taking on greater and greater range and profundity. Undset magnificently depicts the huge force of nature, the power of social pressure, and the deepening over the years of Kristin's consciousness and an attendant proto-existential loneliness. Thanks to Nunnally, we can partake of this vision in all its intoxicating clarity.

Adapted from Katherine A. Powers’ “A Reading Life” column, Boston Sunday Globe, January 15, 2006.