What are your favorite works in translation? That's the question that launches this summer's NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of NBCC members and honorees. (Previous NBCC Reads series dating back to 2007 here.) Tell us why you love the book (in 500 words or less) be it a new one, like Sayaka Murata’s quirky little novel, Convenience Store Woman, or something a bit older, such as Stefan Zweig’s evocative memoir, The World of Yesterday.'The deadline is August 3, 2018. Please email your submission to NBCC Board member Lori Feathers: lori@interabangbooks.com

At night we hear the ghostly wails of children, off in the distance. We conjure passion with partners who don’t exist, or don’t know that we exist. We look into mirrors, warts and all, and perfect specimens stare back. Where others see dingy Brooklyn apartments, we see shining castles. We tilt at windmills, usually on Twitter and Facebook.

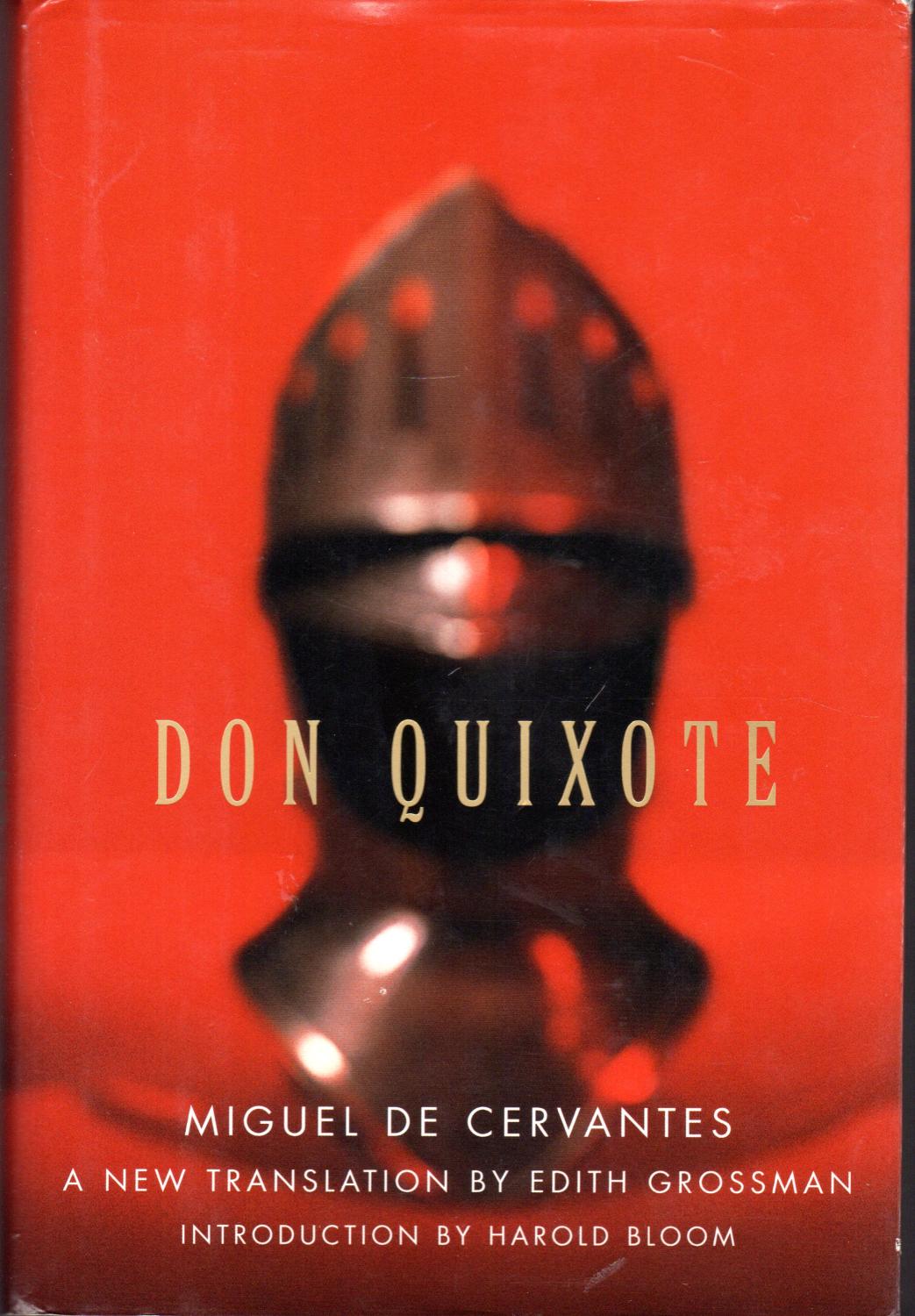

We do all of these things because Don Quixote did them long ago. Four centuries earlier he sprung from the pages of Miguel de Cervantes’ epic, as real and immediate as yesterday. Rich and capacious, Don Quixote contains multitudes, with an all-too-human cast that makes us weep and laugh out loud, shake our heads and nod vigorously. When the virtuoso Edith Grossman brought out her translation in 2004, a choir of critics acclaimed it a leading English version of the ur-novel, one whose DNA blooms in Dickens, Joyce, Proust, and Flaubert. Best known for her supple yet piercing translations of contemporary Latin American masters – she counts two Nobel laureates, Gabriel García Márquez and Mario Vargas Llosa, among her stable – Grossman renders Don Quixote in a polished, discursive, chatty, rollicking English, immersing us in the novel’s many forms: adventure yarn, Socratic dialogue, political satire, literary criticism, cultural elegy, the twinned masks of comedy and tragedy.

Cervantes wrote at a pivotal moment. Along with his contemporaries, Kyd and Shakespeare, he was determined to slay the chivalric tradition he’d inherited. With political upheaval convulsing Europe, with the rise and fall of empires, Cervantes peered into the future, glimpsing flux and chaos. Literature must reflect the changes ahead.

Grossman’s genius is to capture the essential modernity of Cervantes’ tale; no stuffy seventeenth-century diction for her (with the deliberate exception of Don Quixote’s courtly speeches). Harold Bloom calls her “the Glenn Gould of translators, because she, too, articulates every note.” She brilliantly evokes our middle-aged knight errant, literally driven mad by books, and his wisecracking, earthy squire, Sancho Panza — this indefatigable duo encompasses all moods, all the faces we show to the world.

There are sudden reversals of fortune. Plots thicken. Hijinks ensue. The sentences unspool, clause upon clause, buoying us forward. Grossman grasps the enormity of her challenge: translation is, in her famous metaphor, not about using tracing paper but rather recreating one text from another. But she clearly has fun here. Cervantes is an excellent fit for English, “the sheer vibrancy and flexibility of the language and its huge, constantly expanding, wonderfully contaminated, utterly impure lexicon” (as she notes in her short manifesto, Why Translation Matters).

Grossman’s Don Quixote is not without its critics. Yet as a way into this pleasure dome (or labyrinth) of a novel, it entertains — surely a narrative’s chief goal — shaping the here and now.