What are your favorite works in translation? That's the question that launched this summer's NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of NBCC members and honorees. (Previous NBCC Reads series dating back to 2007 here.) Tell us why you love the book (in 500 words or less) be it a new one, like Sayaka Murata’s quirky little novel, 'Convenience Store Woman,' or something a bit older, such as Stefan Zweig’s evocative memoir, 'The World of Yesterday.' Please email your submission to NBCC Board member Lori Feathers: lori@interabangbooks.com

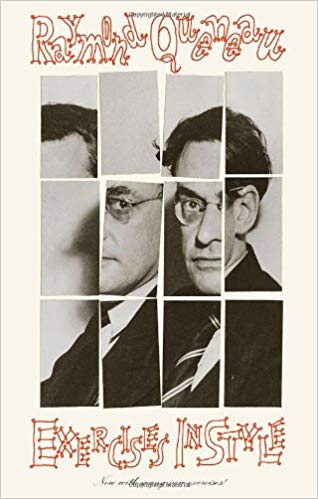

Queneau is a globally-renowned writer and co-founder of the Oulipo movement in literature. In this slim classic (first published in 1981 in English translation by Barbara Wright), he takes a simple story plot — a man getting into an argument with another man on a bus — and writes it in 99 different voice+style combinations. Quite a feat and absolutely wonderful to read.

The idea came to him sometime in the 1930s when he was at a concert listening to Bach’s The Art of the Fugue. Given the infinite variations based on a simple, slight musical theme, he wondered if the same would be possible with literature. And, though this English version has his original 99 exercises, there is a larger volume in French with an additional 124 exercises suggested by Queneau to the reader.

The 99 voice+style exercises here vary between different forms of prose and poetry, formal versus casual tones, polite versus abusive language, literary versus pulp, and so on, along with many varying permutations of all of these too. Not only does Queneau show us the infinite possibilities of language, but he also shows us how much fun it can be to play with language.

“In the S bus, in the rush hour. A chap of about 26, felt hat with a cord instead of a ribbon, neck too long as if someone’s been having a tug of war with it. People getting off. The chap in question gets annoyed with one of the men standing next to him. He accuses him of jostling him every time anyone goes past. A sniveling tone, which is meant to be aggressive. When he sees a vacant seat, he throws himself onto it.

“Two hours later, I meet him in the Cour du Rome, in the Gare Saint-Lazare. He’s with a friend who’s saying: You ought to get an extra button put on your overcoat. He shows him where (at the lapels) and why.”

I should add that the translator, Barbara Wright, is a hero for taking this on because it cannot have been easy to translate all of this from French to English while still maintaining the styles, voice, wordplay, and more. Her introduction is worth a read too.