What are your favorite works in translation? That's the question that launched this summer's NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of NBCC members and honorees. We're posting the last batch thismonth. (Previous NBCC Reads series dating back to 2007 here.)

My favorite is not at all contemporary. Or, is it?

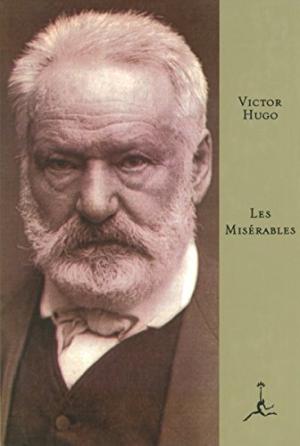

I first encountered Les Misérables by Victor Hugo in my freshman college English class—at least a section of it, the one in which the bishop hands Jean Valjean those candlesticks, having already told him when he arrived: “You are suffering; you are hungry and thirsty; be welcome. And do not thank me; do not tell me that I take you into my house. This is the home of no man, except him who needs an asylum.”

Intrigued, I wanted more. But… almost 2,000 pages? I put it off for decades. Saw the musical. Watched the movies. Finally I bought an abridged copy of close to 1,000 pages (B&N Classics; tr. Charles E. Wilbour; ed. Laurence Porter). Born in Rhode Island, Wilbour was a journalist in New York when he translated Hugo’s work, shortly after the original debuted in 1862. Now Les Misérables is available in over twenty languages. Eight English variations exist.

The antique wording in Wilbour’s translation moves me, even though it’s had criticism. One sentence has burrowed its way into my synapses. Fantine, traveling with three-year-old Cosette, first spies Madame Thérnardier sitting on the doorsill of her inn. The author, knowing where his plot is headed once Fantine leaves Cosette there, quietly muses: “A person seated instead of standing: fate hangs on such a thread as that.” Hugo seized the moment’s essence, ruminating briefly about its portent. Brilliant.

Set against the backdrop of Napoleon III, Les Misérables highlights numerous social problems. Hugo editorialized: “It is an imperative necessity that society should look into these things: they are its own work,” conveying the desperation that can drive people to undertake arduous journeys. “Sometimes we get aground when we expect to get ashore.”

Consider Valjean carrying the wounded Marius through the Paris sewer quicksand:

The water came up to his armpits; he felt that he was foundering; it was with difficulty that he could move in the depth of the mire that he was. The density, which was the support, was also the obstacle….He now had only his head out of the water, and his arms supporting Marius. There is, in the old pictures of the deluge, a mother doing thus with her child.

Imagine the novel Victor Hugo could write today.

Nothing is so like a dream as despair….