What are your favorite works in translation? That's the question that launched this summer's NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of NBCC members and honorees. We're posting the last batch thismonth. (Previous NBCC Reads series dating back to 2007 here.)

Machado De Assis is one of the most overlooked writers who ever lived.

This isn’t a line for literary parties or a sweeping proclamation intended to trigger anger or the silly overstatement of an overzealous grad student. This is a fact.

Many writers who were not overlooked agree with me. I would name them, but the New York Times’s Parul Sehgal saved me the trouble back in June:

“Susan Sontag once called [him] ‘the greatest writer Latin America ever produced.’ To Stefan Zweig, Machado was Brazil’s answer to Dickens. To Allen Ginsberg, he was another Kafka. Harold Bloom called him a descendant of Laurence Sterne, and Philip Roth compared him to Beckett. Others cite Gogol, Poe, Borges and Joyce. In the foreword to ‘The Collected Stories of Machado de Assis,’ published this month, the critic Michael Wood invokes Henry James, Henry Fielding, Chekhov, Sterne, Nabokov and Calvino — all in two paragraphs. To further complicate matters, Machado has always reminded me of Alice Munro.”

This from a review of the omnibus “Collected Stories of Machado De Assis,” which Norton Liveright blessed us with only two months ago.

Luckily, Machado de Assis did not limit himself to short stories. He wrote poetry, plays, essays, criticism, novellas, and novels, one of which is the best novel I have ever read.

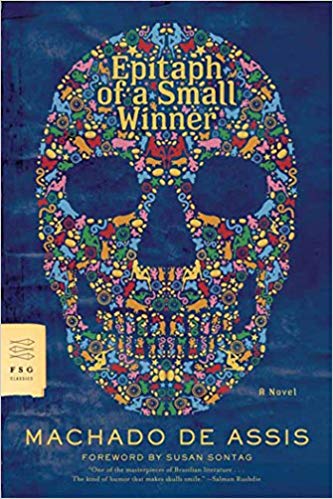

Running a brisk 240 pages, “Epitaph of a Small Winner” is a volume of what de Assis subtitularly calls the “Post-Humous Memoirs of Brás Cubas.” Brás is an upper middle class intellectual dilettante who has led a truly uneventful life. Shortly after he contracts pneumonia and dies, Brás decides to tell us about his trivial existence from the afterlife in brief fragments which come together to tower above the majority of what every single aforementioned writer managed to produce during their time on earth.

De Assis dances across the page in “Epitaph,” presenting existential quandaries in the form of page-long metaphors, ruminating on sex and sadness and pain, paying some attention to his life and the cast of characters that pass through it, but always with a touch of irony and the understanding that the trials and tribulations of human beings are trivial and meaningless. Critics and scholars have characterized Brás Cubas’s outlook on life as one wrought with pessimism and despair and have cited Arthur Schopenhauer as a philosophical influence for the work; I find more hilarity than despair in Brás’s brilliance.

Full chapters of the novel are left blank. Others include shapes, patterns or diagrams. From the dedication (“To the worm who first gnawed on the cold flesh of my corpse, I dedicate with fond remembrance these Posthumous Memoirs”) to the last word, “Epitaph of a Small Winner “is a singular literary masterwork.