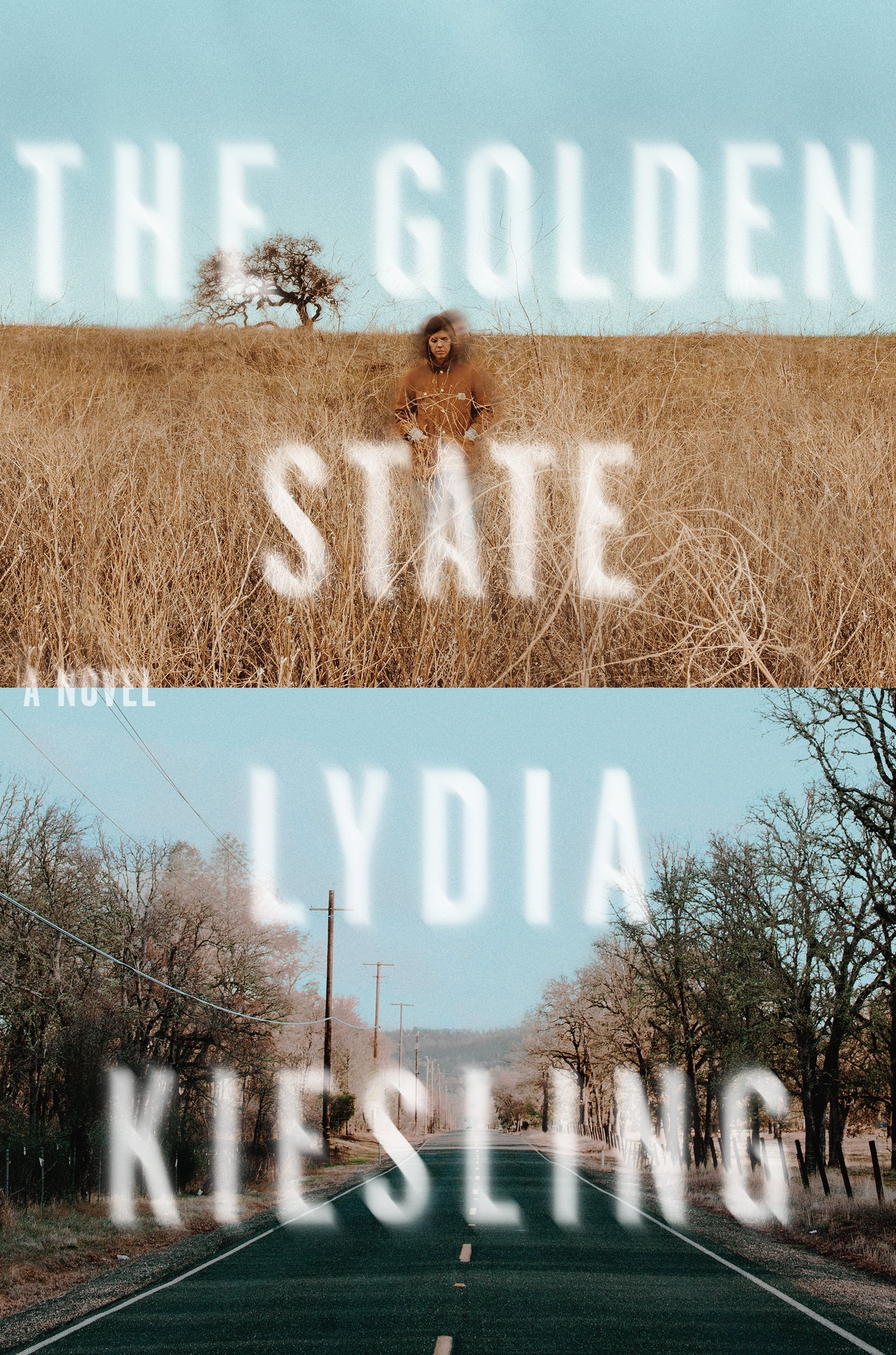

The John Leonard Prize, our annual award based on member nominations and chosen by a panel of member volunteers, is awarded for the best first book in any genre. In advance of the announcement, we're inviting members to contribute appreciations of titles under consideration. (If you're interested in doing so, please email nbcccritics@gmail.com with the subject line Leonard.) Below, NBCC member Joan Frank writes on Lydia Kiesling's debut novel, “The Golden State” (MCD).

Lydia Kiesling's astonishing debut novel, “The Golden State,” sneaks up on you, but quickly cozies right into your lap, heart, mind—suddenly becoming urgently, deliciously necessary. Daphne, a young San Francisco mother with a secure but (tragicomically realistic) suffocating university job, juggles that job alongside care of Honey, her vibrant sixteen-month-old daughter, whilst worrying for the fate of her husband, Engin, a Turkish filmmaker whose green card was wrongfully confiscated in San Francisco Airport and who now languishes near relatives in Turkey, awaiting the untangling of a hopeless hairball of red tape. Daphne is increasingly stressed by his absence, the avalanche of chaotic duties pressing on her, and the uncertainty of everything.

Lydia Kiesling's astonishing debut novel, “The Golden State,” sneaks up on you, but quickly cozies right into your lap, heart, mind—suddenly becoming urgently, deliciously necessary. Daphne, a young San Francisco mother with a secure but (tragicomically realistic) suffocating university job, juggles that job alongside care of Honey, her vibrant sixteen-month-old daughter, whilst worrying for the fate of her husband, Engin, a Turkish filmmaker whose green card was wrongfully confiscated in San Francisco Airport and who now languishes near relatives in Turkey, awaiting the untangling of a hopeless hairball of red tape. Daphne is increasingly stressed by his absence, the avalanche of chaotic duties pressing on her, and the uncertainty of everything.

She goes AWOL.

Tossing little Honey into the car, Daphne drives to her late grandmother's mobile home in a tiny (fictional) northern California foothills town called Altavista. There she'll meet a few old-timers, a handful of bitter secessionists angling to create an independent state called Jefferson out of California's northern half (this part is based, folks, on the actual), and a mysterious, elderly woman traveling alone named Alice, who'll figure importantly in Daphne's and Honey's immediate futures.

Cell service up there is lousy. So are the local eateries.

What pushes this story irreversibly into your heart is its unflagging, gorgeous energy, its sensuous settings, and (delivering these) its raw, funny, smart-as-hell Voice—that of a gifted young woman hyper-attuned to modern absurdities, whose sentences mass and hurtle and scrimmage like a freeway car pile-up. Very much of this narrative describes, blow-for-blow, the fast-forward pitching machine also known as the nonstop mothering of a very small child:

“I give her a string cheese but I panic at the first stoplight remembering that it's a choking hazard in a moving car and first I scrabble my hand back ineffectually and then I pull over before the entrance to the highway so that she can eat the string cheese under supervision, but I have ruined it, and she throws the cheese and cries, and she cries all the way over the bridge and into the customary gridlock by the IKEA, the clogged highway branching off into miles of parking. I smell the foul bay-mud around the base of the bridge, and look across the water to Angel Island and the container ships making their placid hulking way through the Golden Gate and I say “look look look Honey, big boats, BIG BOATS” but she is still crying forty minutes after we've left the house and she is still crying forty minutes after that.”

She had me at “string cheese.”

You'll want to travel with Daphne, have drinks with her, coffee. You'll want to know how on earth she got through it. In fact, she'll show you: each antic, catastrophic, wondrous day of ten days—including an extended sprint (pop-eyed, bearing down on the pages) through a near-symphonic climax—after which you'll never want to leave either Daphne or “The Golden State” again. Thank you, Lydia Kiesling. Please write that next book soon.

Joan Frank is the Northern California author of eight books of fiction and a book of collected essays about the writing life. She frequently reviews literary fiction for the San Francisco Chronicle.