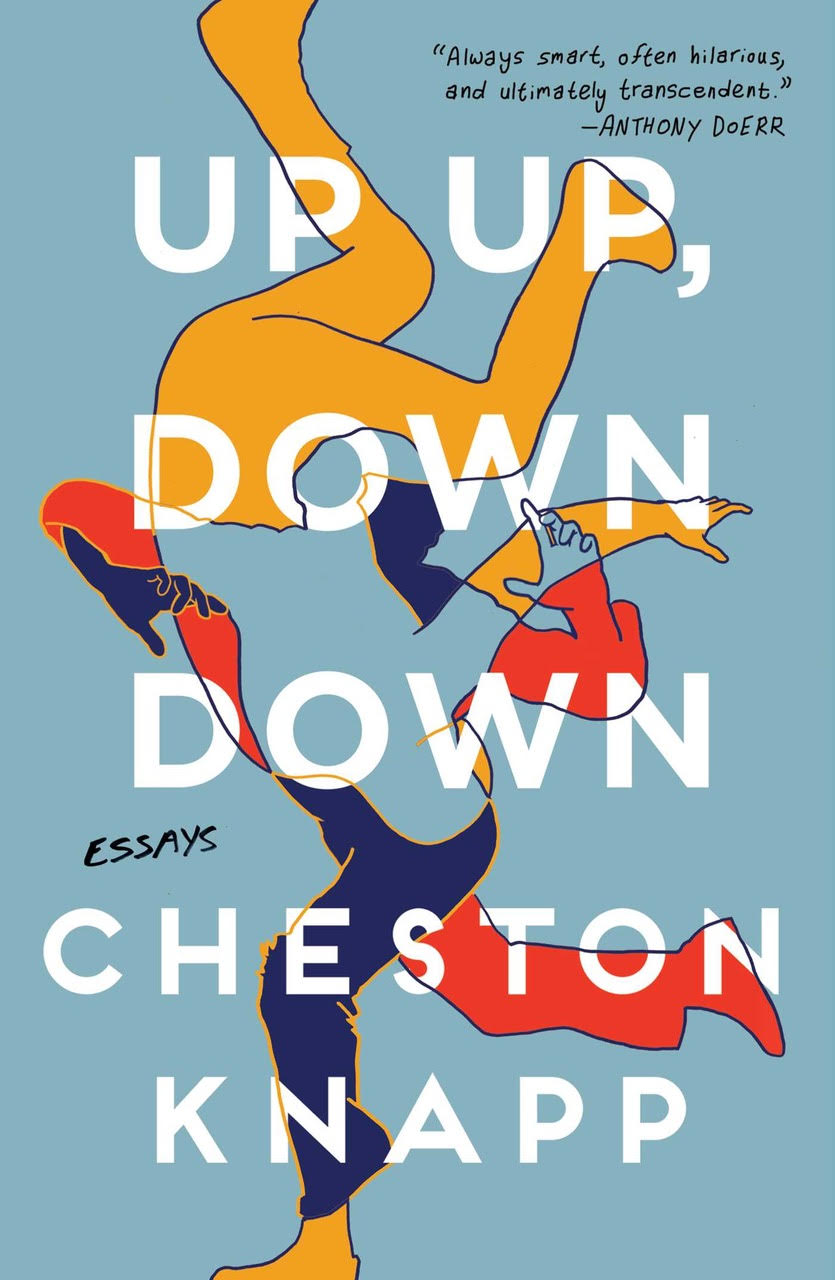

The John Leonard Prize, our annual award based on member nominations and chosen by a panel of member volunteers, is awarded for the best first book in any genre. In advance of the announcement, we're inviting members to contribute appreciations of titles under consideration. (If you're interested in doing so, please email nbcccritics@gmail.com with the subject line Leonard.) Below, NBCC board member David Varno writes on Cheston Knapp's essay collection, “Up Up, Down Down” (Simon & Schuster).

Cheston Knapp’s debut essay collection covers a varied, unruly set of subjects, and they come together in a way that reveals how the different parts of a self (our many phases and interests) can form a whole.

Cheston Knapp’s debut essay collection covers a varied, unruly set of subjects, and they come together in a way that reveals how the different parts of a self (our many phases and interests) can form a whole.

The title comes from the opening control pad inputs of the code for 99 lives in the eight-bit Nintendo game Contra, and it speaks to the author’s admission that he’d grown up with the misguided sense that there would be 99 (infinite) chances at life. It would be a linear game, one you can ‘beat’ at the end, rather than the other way around. “The future, like everything else in my life, wasn’t quite what it used to be.”

Whether revisiting his childhood passion for skateboarding or relating the zealousness of UFO enthusiasts to William James’s theory of spiritual consciousness and his own exploration of religious faith (is up, down also code for high/low?), Knapp explores the rupture between his past and future selves.

Describing a small-time professional wrestling match at a wood-paneled Lions Club an hour south of Portland, Knapp breaks his promise to the friend he’d brought alone, that “At very least it’ll be an experience.” He might be attracted to danger, but when faced with the prospect of flying metal folding chairs, he stands back. The push-pull parallels the fraught relationship Knapp describes in “Faces of Pain” between himself and his father, a man who made him feel in adolescence that he was at risk of being a “mama’s boy.” The essay is agonizing because it shows the patterns that take hold when we maintain distance in the hope of one day being acknowledged.

Often in these essays, Knapp edges toward some kind of experience, a potential marker along the journey toward becoming a whole person, “or something.” In “Beirut,” which recounts a drinking game-turned violent contact sport, he notes the fact that he never got hurt at the table, and often retreated when it grew more dangerous, though he remembers the thrill of being caught up in the moment of sweaty, beery combat with the fraternity brothers, shoulder-checking his opponents as he slides across the slick basement floor to claim an errant ping pong ball for his team, brimming with the belief that he was “right where I belonged.”

Most of the essays have been published elsewhere, but the final two seem to have been written specifically for the book. They rumble with ambition, as Knapp explores themes more deeply and tugs on loose ends. One of the freest, most transcendent moments occurs during a drunken roadside scene after a night celebrating the end of a skateboarding camp (new friends, old passion revisited). With the fratastic Third-Eye-Blind blasting from inside a bro-filled van, Knapp wanders away to take a leak. He thinks about his father’s love and pain, a man he’s both humbled and endeared along the way through the preceding essays, such as when he tells Knapp about a new girlfriend, a “‘cheerleader type’” who “used to get busy with Kenny Loggins.” To which Knapp reflects, “Was Dad boasting about his new Eskimo brother? Bragging about having entered the danger zone? It was as though my past were eroding away.” Amazingly, he manages to write his way back to that feeling from the space of boozy, spliff-clouded darkness, to discover that the less he knows his father, the closer they can become.

On his way back to the van, everyone is singing along to “Jumper” (“Maybe today/you could put the past away…”), which in his mind is the perfect song for the moment—”too perfect, too neat.” Knapp’s book shows how not everything is a story, and that some things are meant to be lived.