The John Leonard Prize, our annual award based on member nominations and chosen by a panel of member volunteers, is awarded for the best first book in any genre. In advance of the announcement, we're inviting members to contribute appreciations of titles under consideration. (If you're interested in doing so, please email nbcccritics@gmail.com with the subject line Leonard.) Below, NBCC board member and autobiography chairman Laurie Hertzel writes on Tessa Fontaine's debut memoir, “The Electric Woman.” This review first ran in the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

Imagine that you have been timid all your life, but your mother – oh, she is a firecracker. She once bought out Chinatown to decorate the house for a Chinese-themed Christmas – hundreds of red paper lanterns and umbrellas and imitation jade cats and a huge dragon that she suspended from the ceiling.

Imagine that you have been timid all your life, but your mother – oh, she is a firecracker. She once bought out Chinatown to decorate the house for a Chinese-themed Christmas – hundreds of red paper lanterns and umbrellas and imitation jade cats and a huge dragon that she suspended from the ceiling.

As a teenager, she skipped school in order to perform stunts on a surfboard. As a young woman, she ran away from her husband and baby – that would be you – to be with the man she truly loved. She never said no to adventure. You always felt pale and meek next to her.

And then imagine that she suffered a series of strokes and is now in a hospital, unable to feed herself or speak, the light gone from her eyes. What do you do? If you're Tessa Fontaine, you spend three years taking care of her and then you abruptly run away and join the circus.

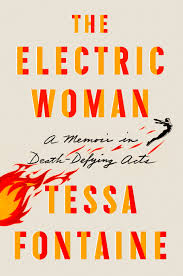

Fontaine's memoir, “The Electric Woman: A Memoir in Death-Defying Acts,” is astounding, amazing, inspiring and a little bit terrifying. It's a story about a mother and daughter's complicated relationship, and it's also a coming-of-age story, of sorts.

It would be safe to say that Fontaine came of age in a most peculiar way – eating fire, charming snakes, escaping from handcuffs and performing as the Electric Woman, illuminating a light bulb with her tongue.

Voice is crucial in memoir, and Fontaine's is just right: trustworthy, intimate and thoughtful. She mulls her mother's illness; she mulls her mother's betrayal; she admits to being terrified of snakes; she weeps in fear the first time she holds one. She's disappointed to find that there is no trick to eating fire, no mirrors. “You eat fire,” she writes, “by eating fire.” And if that's not a metaphor for getting through life, I don't know what is.

Fontaine has a great eye for detail, and she depicts the other circus performers with real affection – not as freaks, but as interesting and fully realized people: Sunshine, “the target half of the knife-throwing act”; Spif, the throwing half; Tommy, the circus manager; Snickers, the clown; those who wash out; and those who stick it out for the whole season.

Fontaine sticks it out for the whole season, spending five months with the World of Wonders and traveling from Florida to Pennsylvania to Minnesota to Kansas to Arkansas and back to Florida, stopping at points in between. The circus workers are hardworking and dedicated to their show, putting it up and tearing it down in city after city, rushing out during a tornado warning to take down the banners, which they can't afford to replace; getting by on four hours of sleep a night for months.

Fontaine's circus adventures are nicely juxtaposed against her mother's long journey of recovery, as both women learn to overcome their fears and meet life's challenges. Fontaine's mother learns not just how to communicate again, and to eat, but how to embrace life with a paralyzed body. (It is no surprise that she heads off to Italy, in a wheelchair.)

And Fontaine herself learns to embrace life with a little of her mother's verve. Over time, she grows from timid to confident, learning how to grapple with the long, heavy tent poles; how to escape from handcuffs; how to open her mouth and swallow a flaming torch as though it were life itself.