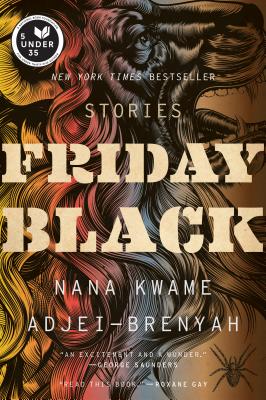

The John Leonard Prize, our annual award based on member nominations and chosen by a panel of member volunteers, is awarded for the best first book in any genre. In advance of the announcement, we're inviting members to contribute appreciations of titles under consideration. (If you're interested in doing so, please email nbcccritics@gmail.com with the subject line Leonard.) Below, NBCC member Hamilton Cain writes on Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah's story collection, “Friday Black” (Mariner).

Children tear-gassed along the Mexican border as their parents legally seek asylum. Corpses from school shootings piled like cordwood. Voters stripped of their right to cast ballots. The creep of fascism.

Children tear-gassed along the Mexican border as their parents legally seek asylum. Corpses from school shootings piled like cordwood. Voters stripped of their right to cast ballots. The creep of fascism.

How should writers respond?

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s searing collection, “Friday Black,” seems tailored to our moment, blending astute observation with gallows humor in a voice that shifts flawlessly across registers, a whisper, a scream, a comic’s routine. Some stories are poignant meditations, others in-your-face satire, with futuristic settings reminiscent of “Brave New World” and “Star Wars.” A guerilla resistance plots its revenge for a slaughter of innocents. Retail workers at a dystopian mall help each other through perils, real and imagined. In the title story a department store throws open its doors to a Black Friday crowd infected with shopping fever and something more sinister; as the narrator observes: “At five in the morning, the lull comes. The first wave of shoppers is home, or sleeping, or dead in various corners of the mall . . . I make it to the food court where the smell of food wafts over the stench of the freshly deceased like a muzzle on a rabid dog.”

And in the hilarious, brutal “Zimmer Land,” white “patrons” swarm a racist theme park, exorcizing their demons by playacting attacks against blacks and Muslims. (The title alludes to George Zimmerman, whose murder of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin birthed the Black Lives Matter movement.) Adjei-Brenyah practices a kind of hyperrealism: his characters move through killing fields that resemble middle-class neighborhoods and clothing boutiques, wielding weapons lifted from a Sharper Image catalog. Trademarks – “PoleFace™,” “OptiLife™” — rain down on them like napalm. Bodies carpet fast-food restaurants. The dying in hospitals levitate in air before falling to earth. We don’t need to look to Iraq and Afghanistan as surreal war zones; we live in them, and they in us.

Adjei-Brenyah’s influences include Colson Whitehead and particularly George Saunders. (“Zimmer Land,” for instance, is an homage to “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline” and “Pastoralia.) His characters yearn to feel whole, “as happy as a sunflower in a field of less radiant sunflowers,” and yet Adjei-Brenyah ultimately pivots away from Saunders’ romanticism. Our nation is one sick, indecent joke, a haunted house of gadgets and zombies and racial violence, backlit by gunfire, more Childish Gambino’s “This Is America” than “Tenth of December.” And yet somehow Adjei-Brenyah remains in perfect control. These stories are lush, heart-stopping, vital, their sentences a music of delicate harmonies and dissonant clashes. Daring and inventive, Friday Black reveals a world in negative, an x-ray of the here and now.