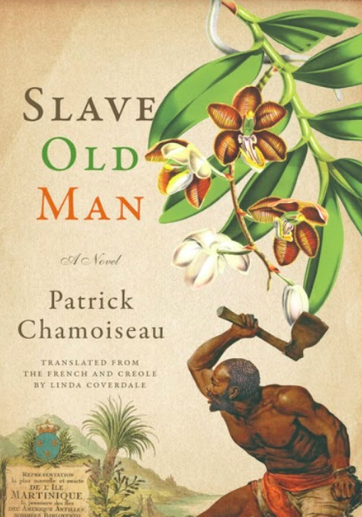

In this 31 Books in 30 Days series leading up to the March 14, 2019 announcement of the 2018 National Book Critics Circle award winners, NBCC board members review the thirty-one finalists. Today, NBCC board member Ismail Muhammad offers an appreciation of fiction finalist Patrick Chamoiseau’s Slave Old Man (The New Press).

Patrick Chamoiseau’s Slave Old Man tells the compact tale of a nameless black Martinican slave who turns fugitive. His flight from subjection is also a flight into an enchanted realm freighted with New World history: the bones of murdered Caribs, fetishes left by maroon slaves, and supernatural entities straight out of Creole folk tales haunt our hero. As a result, Slave Old Man is about a runaway slave the same way Moby-Dick is about a whale: the slave old man might take center stage, but he is really just the scaffolding upon which Chamoiseau hangs an expansive meditation on the world that chattel slavery created, and the ways we are all enfolded in a terrifying history of genocide and enslavement. Chamoiseau asks us how we can write histories of people whom history has forgotten; in doing so, he crafts an epic origin story of African Caribbean culture.

Patrick Chamoiseau’s Slave Old Man tells the compact tale of a nameless black Martinican slave who turns fugitive. His flight from subjection is also a flight into an enchanted realm freighted with New World history: the bones of murdered Caribs, fetishes left by maroon slaves, and supernatural entities straight out of Creole folk tales haunt our hero. As a result, Slave Old Man is about a runaway slave the same way Moby-Dick is about a whale: the slave old man might take center stage, but he is really just the scaffolding upon which Chamoiseau hangs an expansive meditation on the world that chattel slavery created, and the ways we are all enfolded in a terrifying history of genocide and enslavement. Chamoiseau asks us how we can write histories of people whom history has forgotten; in doing so, he crafts an epic origin story of African Caribbean culture.

When we first meet our protagonist, he is a completely remarkable thing, a person only in the vaguest sense of the word. While his fellow Africans reject the abjection that slavery would impose on them, the vieux-nègre is more like a thing than a human, a resource used up in the plantation’s operations, a “mineral of motionless,” “inexhaustible bamboo.” On a plantation wholly bereft of enchantment, he is entangled in numbing mindlessness.

That changes when the master brings a mastiff over from Europe. The dog is monstrous, a beast endowed with “muscles supple as cables” and a preternatural silence. It’s is an object of loathing and fear for the slaves; yet, it is mysteriously linked to our protagonist. Like the slave, the dog “as well had voyaged on a ship for weeks in a kind of horror.” They are united in a shared bondage to the master, and in their subjection to the Middle Passage’s depredations. Our protagonist catches sight of the animal and awakens to a new understanding of his life, “[rediscovering] in the mastiff the catastrophe inhabiting him.” He flees the plantation, aiming his anxious feet towards the “Great Woods” just outside the plantation’s borders. The master follows, setting his mastiff loose.

Slave Old Man is a short book, more of a fable than a novel. Its plot is thin, consisting almost entirely of the slave’s breathless flight from the plantation, and the mastiff’s frenzied pursuit. Chamoiseau’s lush prose undulates with this sense of movement, and just as the slave sinks down into an ancient spring at the novel’s end, we sink into Chamoiseau’s portrayal of a forest pregnant with hallucinatory images: a woman carrying souls in an oxcart, devils hunkering down in trees, people who transform into dogs. Translated with care and nuance by Linda Cloverdale, the novel abandons trite stories about slavery’s demise and Western progress on the question of race. In place of these sentimental tropes, we get a bold, inventive statement on how the ghosts of slavery are rooted in the heart of the present.

Ismail Muhammad is a writer and critic based in Oakland, California, where he is the reviews editor at The Believer.

Review