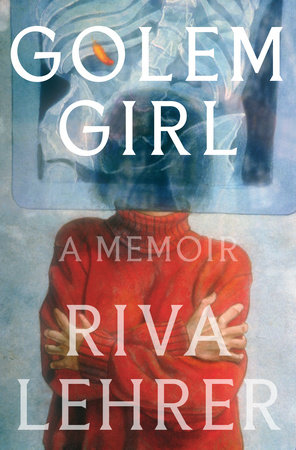

Golem Girl by Riva Lehrer (One World)

Visual artist Riva Lehrer comes to memoir writing in her seventh decade after an illustrious career as a painter best known for grappling with questions of disability. Lehrer was herself born with spina bifida, a congenital defect of the neural tube that required multiple surgeries during her childhood and adolescence. Her physical condition forms the backdrop for a nuanced and poignant account of her upbringing in Cincinnati, her romantic and professional negotiations as a queer Jewish disabled woman, and her intellectual engagement with Chicago’s cultural scene, where she has become an iconic figure. Yet at the core of Golem Girl is a love story, depicting a mother’s fierce devotion for her daughter and that daughter’s emerging independence. The autobiography is in some ways a reversal of the traditional “monster” story, like that of the Golem or Frankenstein, in that the “monstrous” creature—who is obviously monstrous only in the misguided eyes of mainstream society—shakes free of her origins to become an agent of generativity and beauty.

Lehrer does not shy away from capturing the indignities of enduring ableist culture. In one memorable scene at a wedding, her boyfriend’s oblivious uncle offers him a “list of gals you should call” as though she did not exist. Even her own grandfather urges that if she really cares for the boyfriend, she should let him date other women. “Apparently there had been a family conference,” writes Lehrer. “All of these people who loved me believed that Will could not.”

Maybe because of her outsider status—but an outsider with a close-up view, a 21st-century Jane Eyre—Lehrer recognizes the moral knots in the bourgeois tapestry of her family history. She writes of her mother’s relationship with the family’s Black housekeeper, Dorie, self-proclaimed “best friends” in a communion that “looked like love, at least from the pinhole-camera view of a white middle-class child,” but was prisoner to “imbalance, economically, racially—almost in every way one can count.” And she writes of a “nonphysician caretaker” who pursued her sexually when she was hospitalized in Boston at the age of seventeen. She is able to describe this as “a massive professional violation” and yet state that she “did not feel preyed upon,” but “saved” by the secret nature of a relationship unknown to her mother.Golem Girl includes reproductions of the author’s paintings, works as intellectually challenging as they are visually riveting. These images add resonance to the author’s journey. Like her prose, they remind us that surfaces are deceptive, that rarely is life as it first appears. Lehrer has penned a haunting story of devotion and loss, seasoned with age, and told with insight, finesse and a playful side of Jewish wry. It’s monstrously good.